Lately, it seems like every book I read reminds me of one or two others. I don't mean that the book I'm reading seems derivative, but it has tended to have a similar setting or theme that makes me feel like it should be read together with the book it brings to mind. Since I've been on a World War II-era book binge, I suppose this phenomenon shouldn't be surprising.

As soon as I heard about Simon Mawer's

Trapeze, I had to read it. The book tells the story of Marian Sutro, a young Englishwoman who is recruited into Britain's Special Operations Executive as an agent. Winston Churchill's mandate to the SOE was to "set Europe ablaze" by working with local resistance forces to fight Germans in occupied countries, especially France. Marian comes to the SOE's attention because she has a French mother and grew up in Geneva, speaking French.

Marian jumps at the chance to join the SOE, even though it's not at all clear to her what the agency is, or what, exactly, they want from her. She's just looking forward to be doing something exciting for the war effort. In the first part of the book, Marian is recruited and sent off to her training, which includes coding and decoding messages, armed and unarmed combat, stealth killing and explosives. Oh, yes, and a parachuting course, so that the agents can be dropped by moonlight into occupied France. We meet Marian's upper-crusty superiors and her more down-to-earth trainers and fellow agents. Other trainees include the charming and lively Benoit, with whom she begins a relationship, and Yvette, a nervy widow and mother of a young child, who constantly worries she will wash out of the SOE without having a chance to return to her native France.

The second part of the book covers Marian's drop into a village near Toulouse, and her meeting with members of the underground network there. The big action takes place in the third part, in which Marian is sent to Paris on a mission to bring supplies and messages to Parisian agents. The Paris network has been compromised, leaving Marian with few resources and not knowing who can be trusted. This part of the book was nail-bitingly tense, with a frightening and violent climax.

|

| Noor Inayat Khan, SOE agent |

Trapeze immediately brought to mind one of my all-time favorite nonfiction books, Leo Marks's

Between Silk and Cyanide: A Codemaker's War, 1941-1945. Marks was a very young codes officer at the SOE. He supervised a team of women who used brute-force methods to decode messages that had become garbled, and he taught coding techniques to field agents. The men and women who went into the field had only about a 50/50 chance of survival––and they knew it. They just went on with the job; even those who had young children. Many were captured by the Germans, tortured, sent to concentration camps and killed. Marks tells their stories and breaks our hearts. Simon Mawer has had a long fascination with the female agents of the SOE and pays homage to them through this book.

Marian's training description in

Trapeze reminded me of similar scenes in William Boyd's

Restless, with its Eva/Sally character. Their training experiences were remarkably similar, and both had a tough-minded determination to get on with the job.

As the summer Olympics in London approach, it seemed like a good time to read David John's

Flight from Berlin, which revolves around the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. Let me just start by saying this is a formulaic book––but in a good way. It won't improve your mind or make you think deep and important thoughts. John is just a good storyteller, who has a talent for characterization and can make an outlandish plot filled with cartoonish Nazis, numerous chase scenes and zeppelin stowaways seem believable enough to keep your eyes from rolling around too much.

|

| Jesse Owens |

First-time author John's heroine is Eleanor Emerson, a 1932 Olympic gold-medal-winning swimmer who is married to a bandleader and likes to drink, smoke and spend her evenings in nightclubs, sometimes singing with the band. She immediately clashes with delegation chief Avery Brundage over her shenanigans on board the ship taking the team to Europe, and ends up being booted from the team. But she's made herself popular with the press and gets a special correspondent assignment. Once in Berlin, she meets British reporter Richard Denham. In classic Hollywood-movie style, they clash and then come together. They become involved in the story of Hannah Liebermann, a world-class fencer who is the sole Jewish member of the German Olympic delegation and, separately, in the pursuit of a mysterious dossier that the Nazis are desperate to acquire.

The action of the plot moves from the Olympic Games (including a description of Jesse Owens's spectacular long jump win and his surprisingly warm reception by the largely German stadium crowd) to the streets and nightclubs of Berlin, a party at the home of notorious Nazi propaganda chief Josef Goebbels, the famed Tiergarten and, most spectacularly, the zeppelin

Hindenburg.

|

| Eleanor Holm |

David John based his Eleanor Emerson character on real-life Olympian Eleanor Holm, who really was a hard-partying girl married to a bandleader, and whose wild behavior on the cross-Atlantic trip practically provoked Avery Brundage to change his last name to Umbrage and definitely did get him to kick Holm off the team. Like Emerson, Holm used her press popularity to get a correspondent job for the Games. John also based the Hannah Liebermann fencer character on Helene Meyer, the only Jewish member of the German Olympic team. John spices the story with many other characters who existed in real life, most notably Brundage, who infamously pulled two Jewish athletes off the US relay team, and Martha Dodd, the social butterfly daughter of the then-US ambassador to Germany, who (Martha, that is) had lovers who were members of the Nazi SS and another who was in the USSR's diplomatic corps and intelligence service.

Flight from Berlin put me in mind of those guilty-pleasure film thrillers from the 1930s and 1940s, with sneering Nazis played by emigrés who had usually fled the Nazis themselves. It reminded me slightly of Rebecca Cantrell's 2011

Game of Lies, third book in the Hannah Vogel series, in which Hannah is a reporter at the 1936 Olympics too. Although Cantrell's book is painstakingly researched, she doesn't tell nearly as exciting a story, and her Hannah Vogel is a mope, especially compared to Eleanor Emerson. A non-mystery novel that

Flight From Berlin brought to mind was Frank Deford's

Bliss, Remembered, about a US Olympic swimmer who goes to the 1936 Olympics. Eleanor Holm must have been some kind of inspirational! Deford's book had its moments, but much of its dialog was awkward and the story forgettable. More than

Game of Lies or

Bliss, Remembered,

Flight from Berlin reminded me of Erik Larson's

In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror and an American Family in Hitler's Berlin. Larson's story heavily features Martha Dodd, and wonderfully evokes the mixture of excitement, fear and dread that prevailed in Berlin under the Nazis in the 1930s.

I also recently read Alan Furst's

Mission to Paris. In 1938, France walks on a high-tension wire. Germany has re-armed and is on the march. Austria has become part of the glorious Reich, the Sudetenland and Danzig are being vociferously claimed, and the French wait to see what Hitler plans next.

Some of the French have already succumbed, willingly, to what they see as inevitable. Businessmen openly admire the new Germany and use their connections with certain newspapers to propagandize in favor of authoritarianism, falsely positing that anything to the left of that is equivalent to the menace of bolshevism. Too many politicians and bureaucrats are also ready to accept Germany's domination of Europe.

Many of France's refugees, on the other hand, are too well acquainted with the Third Reich to be anything but frightened for the future of Europe and themselves. Embassy and intelligence personnel from other countries, stationed in Paris, anxiously monitor developments and prepare for the worst.

|

| Coco Chanel collaborated with the Nazi occupiers |

Into this seething atmosphere comes Frederic Stahl, an American movie star who has arrived in Paris to make a movie. Stahl was born in Austria under the name Franz Stalka, then lived in Paris for several years. No admirer of the Nazis, Stahl is surprised to find many Germans and German-friendly French in Paris's high society––and just as surprised to find himself assiduously courted by them.

When courting is followed by pressure and threats by Germany's agents to get Stahl to act, essentially, as a celebrity supporter of the Reich, Stahl decides to become a player on the other side of the intelligence and influence war being waged.

Though I read a lot of World War II-era fiction, I have not been a fan of Alan Furst in the past, largely because I haven't been engaged by his characters. But I'm very much an admirer of this book––even if I'd still say characterization isn't Furst's strong suit. You might think that a pre-war espionage story can't be compelling, but Furst masterfully evokes feelings of tension and frustration, as we see the inevitable cataclysm building, and Stahl's efforts to hold back the storm. He also seems effortlessly to put the reader into the scenes he's created, so that we are there on the Paris streets, at the glittering parties, in the cafés, on the movie set.

In some ways, this book also reminded me of William Boyd's

Restless. Not, as with

Trapeze, in the part about the agent's training, but in the story of an agent engaged in pre-war intelligence; in

Restless, a female agent working in the US for Britain, trying to move the US away from isolationism. I recommend both books for fascinating views of how war works before the shots are fired.

Note: I was given advance reading copies of

Flight from Berlin (available July 10) and

Mission to Paris (available June 10) for review. Parts of my review here appear under my Amazon user name on the Amazon product pages.

In Trapeze (Other Press, 2012), which is the predecessor to Tightrope, Simon Mawer gives us the story of a fictionalized SOE agent named Marian Sutro. She's English and French, grew up in Switzerland and moved to England with her family as things got dangerous on the European continent before World War II broke out. She had friends in France, especially Clément, the young scientist whom she'd had a crush on for years. When Germany overran France, it seemed very black and white to her; a place and people she loved were in danger from an evil invader and she wanted to help.

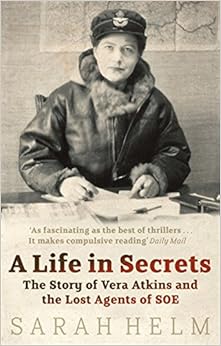

In Trapeze (Other Press, 2012), which is the predecessor to Tightrope, Simon Mawer gives us the story of a fictionalized SOE agent named Marian Sutro. She's English and French, grew up in Switzerland and moved to England with her family as things got dangerous on the European continent before World War II broke out. She had friends in France, especially Clément, the young scientist whom she'd had a crush on for years. When Germany overran France, it seemed very black and white to her; a place and people she loved were in danger from an evil invader and she wanted to help. When Tightrope begins, the war is in its last weeks and Marian is coming home. She wasn't an SOE agent in France for long. She was betrayed, captured by the Nazis, tortured and finally sent to Ravensbrück, the notorious prison camp for women near Berlin, where many real-life SOE female agents were sent. (By the way, I highly recommend Sarah Helm's masterful history of the camp: Ravensbrück: Life and Death in Hitler's Concentration Camp for Women (Nan A. Talese, 2015).)

When Tightrope begins, the war is in its last weeks and Marian is coming home. She wasn't an SOE agent in France for long. She was betrayed, captured by the Nazis, tortured and finally sent to Ravensbrück, the notorious prison camp for women near Berlin, where many real-life SOE female agents were sent. (By the way, I highly recommend Sarah Helm's masterful history of the camp: Ravensbrück: Life and Death in Hitler's Concentration Camp for Women (Nan A. Talese, 2015).)

After the US drops atomic bombs on Japan, develops the far more powerful hydrogen bomb and seems to be seriously considering a preemptive strike on the Soviet Union, she wonders what was the point of all the sacrifice only a few years before, if World War III is now on the doorstep. Slowly, inexorably, Marian is drawn back into the ambiguous world of intelligence, with its agents, counter-agents, double agents and moles. Marian is once again in an environment where security and life itself depend on hierarchies, networks and groups. Will her choices lead to safety or betrayal?

After the US drops atomic bombs on Japan, develops the far more powerful hydrogen bomb and seems to be seriously considering a preemptive strike on the Soviet Union, she wonders what was the point of all the sacrifice only a few years before, if World War III is now on the doorstep. Slowly, inexorably, Marian is drawn back into the ambiguous world of intelligence, with its agents, counter-agents, double agents and moles. Marian is once again in an environment where security and life itself depend on hierarchies, networks and groups. Will her choices lead to safety or betrayal?