I'm in that frantic state some of us reach when preparing to hit the road: dashing from room to room, grabbing clothes and stuffing them willy nilly into a duffel bag with one hand, while watering houseplants with the other hand. Whirling around my legs are the dogs, hysterical now that the quilt they use when I take them along has been put in the car.

I'm in that frantic state some of us reach when preparing to hit the road: dashing from room to room, grabbing clothes and stuffing them willy nilly into a duffel bag with one hand, while watering houseplants with the other hand. Whirling around my legs are the dogs, hysterical now that the quilt they use when I take them along has been put in the car. Before we lay rubber down the driveway, I want to tell you about a book I read last night, Lin Enger's The High Divide (Algonquin Books, September 2014). It's about a man named Ulysses Pope, who disappears from his home on the Wisconsin prairie on a quest for redemption, and the quests of his wife and their two young sons to find him.

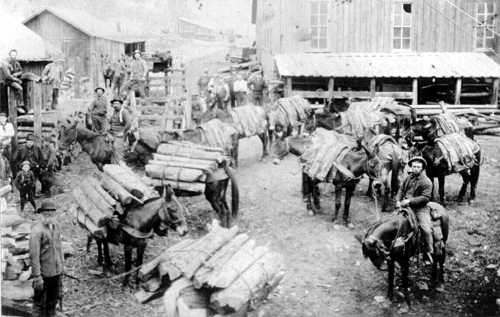

Before we lay rubber down the driveway, I want to tell you about a book I read last night, Lin Enger's The High Divide (Algonquin Books, September 2014). It's about a man named Ulysses Pope, who disappears from his home on the Wisconsin prairie on a quest for redemption, and the quests of his wife and their two young sons to find him.Their 1886 journeys are traceable on a sketched map of the State of Minnesota and the Dakota and Montana Territories in the book's front. Ten years earlier, Custer and his 7th Cavalry Regiment blundered into the Battle of the Little Big Horn in Montana. Cheyenne, Crow, and Arapahoe Indians have been driven onto reservations, where promised provisions from the U.S. government don't always arrive. Buffalo Bill's Wild West show is making annual appearances. Buffalo, which once roamed the West in uncountable herds, have been shot for sport from passing trains and killed by market hunters––and now number in the hundreds.

The disappearance of Ulysses is related to his baptism by an itinerate preacher. Rather than feeling purged, Ulysses feels called to answer for more than his mortal soul. He and his Danish wife, Gretta, love each other, but Ulysses isn't by nature a talker, and Gretta doesn't by nature invite him to confide. While Ulysses feels guilty decades later over the accidental death of a girl's collie, the beautiful and strong-willed Gretta has "a ruthless capacity for self-protection," rarely allowing herself to think about her losses or committing her sympathies beyond a point at which they might cause her damage. Without Ulysses, Gretta looks for more work. Six weeks go by, and then her sons, 16-year-old Eli and his sickly younger brother, Danny, take off without a word. Gretta, abandoned by most of her friends and her men, and hounded for money and favors by the repulsive Mead Fogarty, owner of the title on the Popes' house, has had enough. She heads out to find Ulysses, Eli, and Danny––and discovers how little she knows about the man she calls her husband.

The disappearance of Ulysses is related to his baptism by an itinerate preacher. Rather than feeling purged, Ulysses feels called to answer for more than his mortal soul. He and his Danish wife, Gretta, love each other, but Ulysses isn't by nature a talker, and Gretta doesn't by nature invite him to confide. While Ulysses feels guilty decades later over the accidental death of a girl's collie, the beautiful and strong-willed Gretta has "a ruthless capacity for self-protection," rarely allowing herself to think about her losses or committing her sympathies beyond a point at which they might cause her damage. Without Ulysses, Gretta looks for more work. Six weeks go by, and then her sons, 16-year-old Eli and his sickly younger brother, Danny, take off without a word. Gretta, abandoned by most of her friends and her men, and hounded for money and favors by the repulsive Mead Fogarty, owner of the title on the Popes' house, has had enough. She heads out to find Ulysses, Eli, and Danny––and discovers how little she knows about the man she calls her husband. The High Divide is an exploration of guilt and redemption, the corrosive character of terrible secrets, the nature of home, and the costs of racial hatred and traditional gender roles, set against the backdrop of the American West in the 1800s. It casts several historical events in such personal terms that it brought me to tears. There's no mistaking the western nature of this gripping book, but you don't need to love westerns to enjoy it. Its lyrical writing describes a man with a face "like a baked apple, riven and dark, who spent the better part of an hour cleaning his teeth with a length of horsehair and then his toenails with a Bowie knife." A boy reminds Gretta of a muskrat, with a "nose flat against his face and a mouth perennially ajar, as if he lacked the energy to close it." Stars in the western sky are so thick "some giant hand might have skimmed cream from the pail and tossed it up against the firmament."

The High Divide is an exploration of guilt and redemption, the corrosive character of terrible secrets, the nature of home, and the costs of racial hatred and traditional gender roles, set against the backdrop of the American West in the 1800s. It casts several historical events in such personal terms that it brought me to tears. There's no mistaking the western nature of this gripping book, but you don't need to love westerns to enjoy it. Its lyrical writing describes a man with a face "like a baked apple, riven and dark, who spent the better part of an hour cleaning his teeth with a length of horsehair and then his toenails with a Bowie knife." A boy reminds Gretta of a muskrat, with a "nose flat against his face and a mouth perennially ajar, as if he lacked the energy to close it." Stars in the western sky are so thick "some giant hand might have skimmed cream from the pail and tossed it up against the firmament."The High Divide reminded me a bit of Patrick deWitt's Booker-shortlisted novel, The Sisters Brothers (reviewed here), and James McBride's The Good Lord Bird (see review here) in their depictions of how tough life could be in earlier America. It's too bad some folks made it worse than tough.