Most of the time, I like to read about all kinds of excitement that takes place far away from my back yard. This fall, my reading wish list will take me across the pond to some foreign locations I

would like to visit someday in person.

Most of the time, I like to read about all kinds of excitement that takes place far away from my back yard. This fall, my reading wish list will take me across the pond to some foreign locations I

would like to visit someday in person.It’s always nice to see a few new books coming out from both Francophiles written in English and works written in French and translated. My list has one of each of these.

I first encountered the charismatic Antoine Verlaque in M. L. Longworth's Death at the Chateau Bremont, the first in a series set in Provence. He is the Chief Investigating Magistrate of Aix, and he and an old friend of his, law professor Marine Bonnet, teamed up to solve the

murder of two brothers. I'm looking forward to the fourth mystery in the series, Murder on the Île Sordou (Penguin, September 30). Verlaque and Bonnet are taking a vacation on a small island off the coast of Marseilles, where they are staying at a 1960s retro hotel. This turns out to be no vacation from

crime, though. The hotel is filled with interesting company, including poets, actors, some Americans and the inevitable rude person. I'll let you guess who the murder victim is.

I first encountered the charismatic Antoine Verlaque in M. L. Longworth's Death at the Chateau Bremont, the first in a series set in Provence. He is the Chief Investigating Magistrate of Aix, and he and an old friend of his, law professor Marine Bonnet, teamed up to solve the

murder of two brothers. I'm looking forward to the fourth mystery in the series, Murder on the Île Sordou (Penguin, September 30). Verlaque and Bonnet are taking a vacation on a small island off the coast of Marseilles, where they are staying at a 1960s retro hotel. This turns out to be no vacation from

crime, though. The hotel is filled with interesting company, including poets, actors, some Americans and the inevitable rude person. I'll let you guess who the murder victim is.Just like the surroundings, the answer to the puzzles lie in the past. This should be a nice way to spend a fall weekend.

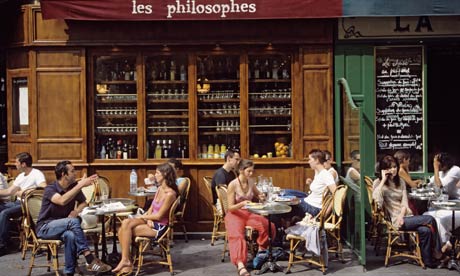

While you are in France, you might as well take a short jaunt over to Paris, because this next author writes novels with an authentic feel of Paris; its streets, its neighborhoods,

and the way its police work, as well as the life on the streets.

While you are in France, you might as well take a short jaunt over to Paris, because this next author writes novels with an authentic feel of Paris; its streets, its neighborhoods,

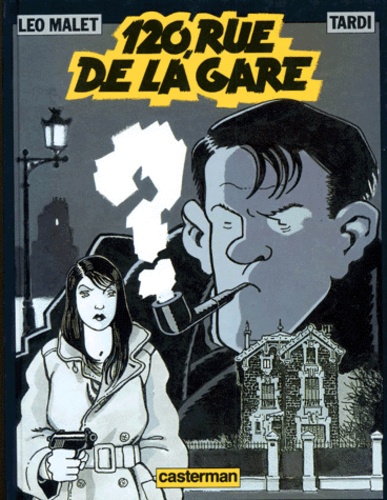

and the way its police work, as well as the life on the streets.Frédérique Molay's first book, The 7th Woman, took France by storm in 2006 and it was finally translated into English by Anne Trager in 2012. Next in the series is Crossing the Line (translated from the French by Anne Trager; Le French Book, September 23).

The Molay books feature super cop Chief of Police Nico Sirsky, who heads the top criminal investigation division in Paris, "La Crim." Sirsky is just returning to work after recovering from a gunshot wound. It is Christmas now in Paris, and Sirsky has romance on his mind. But his first day back at work sets him on the trail of a jewel thief, as well as dealing with a very peculiar disturbing message in a severed head. As in any busy metropolitan police station, the crimes begin to pile up and the crack homicide detectives have their work cut out for them as they work to distinguish the naughty from the nice.

If you have a craving for a bit of la dolce vita,

including skiing, as well as après ski with wine, pasta and skullduggery, take a look at David P. Wagner's Death in the Dolomites (Poisoned Pen Press, September 8), which is also on the fall menu.

If you have a craving for a bit of la dolce vita,

including skiing, as well as après ski with wine, pasta and skullduggery, take a look at David P. Wagner's Death in the Dolomites (Poisoned Pen Press, September 8), which is also on the fall menu.This is the second in a series featuring Rick Montoya, who is a 30-something American with a mother from Rome and an American father, from New Mexico. Rick has chosen to live in Rome and makes his living as a translator. But in this story, he is taking a break from his translating business to meet Flavio, a friend from his University of New Mexico days, for a skiing vacation.

It doesn't matter exactly what time of year it is in the Dolomites, which are in the southern alpine area, because it snows early and often. Many of the villages in these parts have prospered in the postwar days from flatlanders of many sorts, mostly skiers and hikers. Now, heavy snows have brought Rick and Flavio, but also criminals, who have found that deep crevasses are ideal for hiding bodies.

When an important banker goes missing, Rick's uncle, who is a policeman in Rome, asks him to aid the local police. A body found on the slopes happens to be an American. Rick is in the perfect spot to exercise his amateur sleuthing abilities. There are beautiful women, hair-raising escapades and more to entertain Rick before his adventure is over.

There are plenty of reasons to visit Denmark via crime books, and Jussi Adler-Olsen's Department Q books are among the best. These mysteries feature Chief Detective Carl Mørck, who used to be one of Copenhagen's best homicide detectives. After he was almost killed in an incident in which two of his colleagues were killed, he lost heart because he blamed himself.

When he returned to work, he was given a new assignment to investigate cold cases. He understood just how important his

new job was when he was allotted a broom closet in the basement for his new office. After he finally finagled a computer and an assistant, he settled back to put his feet up and snooze his life away. Somehow it doesn't work out that way.

When he returned to work, he was given a new assignment to investigate cold cases. He understood just how important his

new job was when he was allotted a broom closet in the basement for his new office. After he finally finagled a computer and an assistant, he settled back to put his feet up and snooze his life away. Somehow it doesn't work out that way.Mørck's assistant, Assad, is a wannabe Sherlock Holmes and Department Q, as it is termed, becomes successful. Eventually, Department Q gets another assistant, Rose, and a new boss.

Jussi Adler-Olsen's fifth Department Q novel is The Marco Effect (Dutton, September 9). The Marco of the title is Marco Jameson, a 15-year-old gypsy boy who has been forced to beg and steal from his infancy by his evil

uncle Zola. But Marco has dreams of leaving this dreadful life. His uncle has plans to cripple him to keep him under his thumb, but Marco flees.

Jussi Adler-Olsen's fifth Department Q novel is The Marco Effect (Dutton, September 9). The Marco of the title is Marco Jameson, a 15-year-old gypsy boy who has been forced to beg and steal from his infancy by his evil

uncle Zola. But Marco has dreams of leaving this dreadful life. His uncle has plans to cripple him to keep him under his thumb, but Marco flees.When Marco sees a poster of a missing man, he realizes that he has seen him before and he may have information that would be helpful to the police––and may save his own life. Department Q and Marco together make a case that leads from Denmark to Africa, from low to high, and who knows to what ends. This is powerful stuff. More than enough to get Mørck juiced up.

Since I am always looking for more exotic locations as backdrops to murder, I am looking forward to Deon Meyer's new book, Cobra (Atlantic Monthly Press, October 7).

Meyer's books are not for the faint of heart. They take place in South Africa––post-apartheid, but not post- cruelty, murder, fear and desperation. Into this mix comes Benny Greissel, who has hit bottom and bounced a few times, a police detective in a force that is undermanned and undertrained, while at the same time at odds with private security agencies with their own agendas and a citizenry that is as lawless as the Wild West.

Since I am always looking for more exotic locations as backdrops to murder, I am looking forward to Deon Meyer's new book, Cobra (Atlantic Monthly Press, October 7).

Meyer's books are not for the faint of heart. They take place in South Africa––post-apartheid, but not post- cruelty, murder, fear and desperation. Into this mix comes Benny Greissel, who has hit bottom and bounced a few times, a police detective in a force that is undermanned and undertrained, while at the same time at odds with private security agencies with their own agendas and a citizenry that is as lawless as the Wild West.In Cobra, Benny is part of a multiracial, multicultural, multilingual team called the Hawks. They are an elite team tracking a professional hit man who leaves a calling card at the site of each hit––a cartridge engraved with a spitting cobra. Benny and crew are not exactly sure who's against them; the top brass of the police themselves, Britain's MI6, or South Africa's own State Security Agency. Besides these, Benny has his own demons to battle. This story looks like a wild pulse-pumping ride that has heart attack written all over it.

One place that has always intrigued me, but I have never

really wanted to visit there in any frigate except a book, is that lonely and seemingly desolate Himalayan country, Tibet. The novels that have been my main

introduction to that remote place are those by Eliot Pattison, featuring ex-police

Inspector Shan Tao Yun, who spent his early days in Tibet in a gulag aerie among

imprisoned monks whom the Chinese were trying to reeducate––or else. Pattison's

latest offering, like those before, is a mirror of the struggle of the indomitable

Tibetans to retain their culture and autonomy.

One place that has always intrigued me, but I have never

really wanted to visit there in any frigate except a book, is that lonely and seemingly desolate Himalayan country, Tibet. The novels that have been my main

introduction to that remote place are those by Eliot Pattison, featuring ex-police

Inspector Shan Tao Yun, who spent his early days in Tibet in a gulag aerie among

imprisoned monks whom the Chinese were trying to reeducate––or else. Pattison's

latest offering, like those before, is a mirror of the struggle of the indomitable

Tibetans to retain their culture and autonomy.In Soul of the Fire (Minotaur Books, November 25), Shan and his friend Lokesh, whom he met originally in prison, are grabbed by the Chinese authorities. Despite their fear that their subversive activities of aiding the Tibetans have been discovered, they keep their calm. Shan's fear turns to confusion when he finds that he has been put on a special international commission to investigate Tibetan suicides, then to dismay when he begins to discover that some of these suicides are indeed murders. Unfortunately, the imprisonment of Lokesh is being used as a pawn to deter Shan's investigations.

I expect that this latest novel, like all of Pattison's stories, will take you in its grip and stir you up. You might be reminded of what a varied and complicated world there is out there.

There are more upcoming books I want to tell you about, a good many of them from the British Isles. I'll fill you in soon about them.