|

Following a search tangent is like cutting

off a head of the Lernaean Hydra. Many

more search possibilities pop up. |

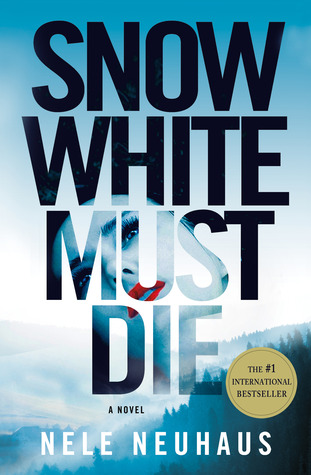

Snow White Must Die by Nele Neuhaus, trans. by Steven T. Murray

Please cut me some slack today, as I give in to searchtangentitis, in which a word or idea prompts me to follow research trails that become increasingly unrelated until the original reason for searching has been lost. Nele Neuhaus's

Snow White Must Die is full of searchtangentitis triggers. Just to give you a flavor of one of the trails I followed, I researched the German fairy tale and the Brothers Grimm, of course, and from there I went to dwarfs and apple varieties,

Tales of Monkey Island (Disney, who made a Snow White movie, bought LucasArts, maker of the game

Monkey Island), Haiti (an island), Tonton Macoute (scary-as-hell Haitian paramilitary group), wonton soup, Great White sharks, and Henry VIII. You get the idea. Since this is Friday, and

Read Me Deadly has an "all bets are off" policy on Fridays, I'll indulge my searchtangentitis by giving some starting points for research as I talk to you about Neuhaus's book.

Snow White Must Die

Snow White Must Die's prologue is a dreamy, tender scene reminiscent of the fairy tale. In a hidden place, an unknown man visits a recumbent woman, whom he calls Snow White. He knows she's dead, and, judging from her stiff and leathery skin, she died years ago. (→

mummy,

a list of mummy movies,

Steve Martin as King Tut,

Nele Neuhaus)

The scene shifts, and it's Thursday, November 6, 2008. Famous German actress Nadia von Bredow is picking up her childhood friend, Tobias Sartorius, outside the Rockenberg Correctional Facility. Now 30 years old, Tobias served a 10-year sentence for the 1997 murders of two teenage girls, Laura Wagner and Stefanie Schneeberger. Laura was his ex-girlfriend, and Stefanie was his current girlfriend when they were last seen, entering Tobias's house. Tobias claims that his memory about what happened that night is a "black hole," and the bodies were never found. He was convicted on eyewitness testimony, circumstantial evidence, and blood stains on his clothes, in his room, and in the trunk of his car. Other physical evidence was found hidden in his house, and the murder weapon was found hidden outside. (→

international homicide rate,

black hole,

forensic crime fiction,

amnesia)

When Nadia drops off Tobias at his family home in the Taunus Mountains village of Altenhain, Tobias is shocked by what he finds. His father, Hartmut, is a wreck, and the farm is strewn with trash. Hartmut's once-thriving restaurant has closed. His parents have divorced, and his mother, Rita Cramer, lives in Bad Soden. Tobias, who had planned to stay a few days, decides to help his father by cleaning up the property. When Tobias discovers one of his father's friends has taken financial advantage of him, he vows to stay until he can figure out what happened 11 years ago. This will not be easy, because the villagers are furious that Tobias has dared to return. A campaign of harassment begins. (→

Taunus Mountains,

The Wall Street Journal,

musophobia,

German politics)

Among the few people who are friendly are Claudius Terlinden, the most powerful man in the village, and the father of Tobias's former best friend, Lars; Terlinden's autistic son, Thies; and a 17-year-old newcomer named Amelie Fröhlich, who works at the Black Horse. Amelie is friendly with Thies, and lives with her father and stepmother in the Schneebergers' old house. Everyone notices that Amelie has an "almost spooky" resemblance to the murdered Stefanie Schneeberger, who was nicknamed Snow White. Amelie has the "same finely etched and alabaster-pale facial features, the voluptuous mouth, the dark, knowing eyes." Until Tobias's arrival, Amelie found the villagers as interesting "as a sack of rice in China." Now she's obsessed with finding out about the old murders. (→

Altenhain,

autism,

graffitti art,

snowflakes)

While Tobias deals with village hostility and a budding romance with Nadia, two significant events happen outside of Altenhain: a backhoe operator at a long-closed airfield in Eschborn discovers human bones and a skull in an empty underground jet fuel tank, and Tobias's mother is hospitalized in a coma after she's shoved off a Bad Soden pedestrian overpass and lands on a car passing below. Investigating these two crimes are Detective Inspector Pia Kirchhoff and her superior, Detective Superintendent Oliver von Bodenstein, who soon follow the evidence to Altenhain. There, they receive little cooperation. Pia notes discrepancies in the evidence that sent Tobias to prison, but what is she to think about Tobias's guilt when Amelie disappears? Man, there is

no shortage of secrets in Altenhain. (→

prehistoric brain surgery,

Freud on guilt,

Patricia Highsmith,

"guilt"-tagged movies,

BMW cars)

Snow White Must Die is a beautifully atmospheric German thriller about a search for justice, involving themes of guilt and redemption, outsiders vs. insiders, and loyalty and betrayal. The village's cultural mores are fascinating, as are the topical issues in mental health and crime. It's the fourth book in the Bodenstein-Kirchhoff series, although so far it's the only one translated into English. Translator Steven T. Murray has done an excellent job. After the flow of Scandinavian crime fiction, perhaps we'll finally see more mysteries from Germany trickling in. (→

thriller genre,

atmospheric optics,

outsider art)

German cops, like cops everywhere, juggle personal loyalty to each other with loyalty to the force, and demands of work and family. I liked Neuhaus's cops. Bodenstein is the son of a countess (when he is wounded, Pia laughs to see his blood is red, rather than blue) and father of three children. Pia says he's Cary Grant handsome and charming. (Does Bodenstein remind you at all of Dorothy L. Sayers's Lord Peter Wimsey or Elizabeth George's Thomas Lynley?) Bodenstein would be happier if Cosima, his movie-producer wife, stuck to Kinder, Küche, Kirche. Their relationship has been strained since their Mallorca vacation was interrupted by Bodenstein's job. Bodenstein is now miserable because he suspects that Cosima is having an affair. Pia also has distractions: Bodenstein isn't his usual self, her ex-husband is in a messy spot, and her farm remodeling plans were denied a permit. Despite these issues, the 41-year-old Pia is happy. Her lover, Christoph Sander, is a zoo director whose smile "always triggered in Pia the almost irrepressible desire to throw herself into his arms." (→

Cary Grant movies,

German beer,

Life of Pi)

I also enjoyed a peek at Germany's law enforcement and legal systems. A couple of things struck me: for murder, there's no statute of limitations in the US, but there's a 30-year statute of limitations in Germany. When those human bones are discovered in the old airfield fuel tank, careful forensic analysis to determine how long it's been since death is crucial. And, I was surprised that Tobias could study to become a locksmith while in prison; would that be allowed here? (→

statute of limitations,

the Wright brothers,

explore human anatomy,

list of films featuring extraterrestrials)

Finally, Neuhaus repeatedly uses the Snow White colors⎯"white as snow, red as blood, black as ebony"⎯to gorgeous effect in descriptions of the winter settings, names (

e.g. the Ebony Club, Schnee[snow]berger), and characters' appearances, emotions (

e.g., black despair, white rage, red embarrassment), and relationships. Scenes alternate between the villagers in Altenhain and the investigating cops, but there's no trouble following the action. The plot is timely and twists smartly. Although the final quarter could have been trimmed, the suspense is well handled, with skillful misdirection and foreshadowing. Nele Neuhaus's

Snow White Must Die was already an international best-seller when it was published by Minotaur Books in 2012. It's no wonder. I enjoyed it, and I'm hoping for more.

.png)