Dante Alighieri's Inferno, the first part of his epic poem Divine Comedy, has inspired many tributes since it was written seven centuries ago. From writers like Milton and Marx, to Craig Johnson, Dante's poetic vision of hell has influenced literature. Musicians, from opera to Celtic music, have based their works on some themes of this same poem. Many painters have tried to depict the reality of what Dante wrote. Wildly popular in its time, it was the first work of literature written in the vernacular and thus accessible to every man or woman (if they could read). It is on the list of books I plan to read.

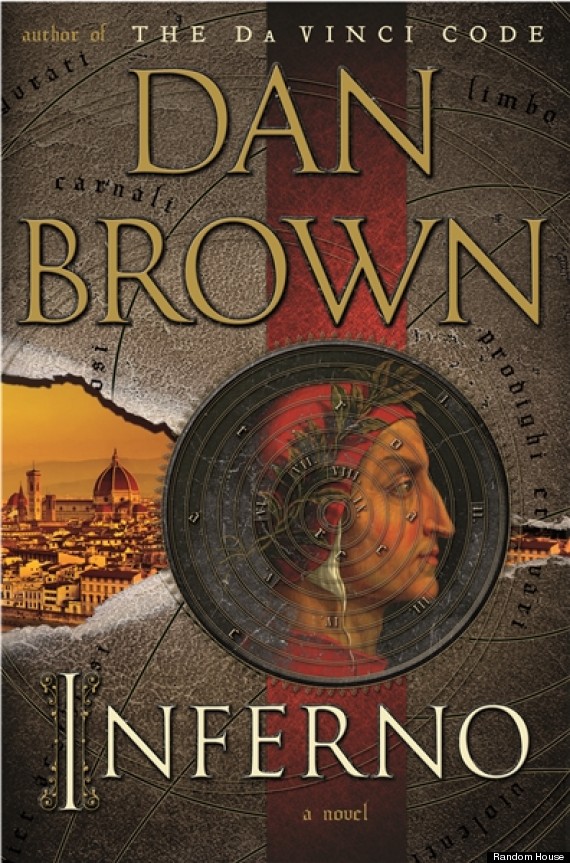

Dante Alighieri's Inferno, the first part of his epic poem Divine Comedy, has inspired many tributes since it was written seven centuries ago. From writers like Milton and Marx, to Craig Johnson, Dante's poetic vision of hell has influenced literature. Musicians, from opera to Celtic music, have based their works on some themes of this same poem. Many painters have tried to depict the reality of what Dante wrote. Wildly popular in its time, it was the first work of literature written in the vernacular and thus accessible to every man or woman (if they could read). It is on the list of books I plan to read.Dan Brown is well known for tackling historical subjects and causing great controversies over some of his ideas. There were plenty of readers who couldn't separate fact from fiction in his early works. In Inferno (Doubleday, 2013), Brown confronts modern problems facing the world today.

(Warning: Lots of plot description ahead, but not mystery spoilers.)

The saga begins when Robert Langdon wakes up from a nightmare, shouting. He finds himself in a hospital bed with absolutely no recollection of how he'd gotten there. Or where he'd been. He assumes he must have been in an accident, because he has stitches in his head––as well as amnesia.

The saga begins when Robert Langdon wakes up from a nightmare, shouting. He finds himself in a hospital bed with absolutely no recollection of how he'd gotten there. Or where he'd been. He assumes he must have been in an accident, because he has stitches in his head––as well as amnesia.In his nightmare, he'd been calling out something that sounds like "very sorry." It is not until he looks out the window that he realizes that he is in Italy––Florence to be specific. He is positive that he began his day at Harvard, where he is well known as a professor of Art History and Symbology.

A doctor comes into his room and introduces herself as Sienna Brooks, but before many more words come out of her mouth, an armed assassin bolts into the room, kills one person and is aiming for Langdon. Sienna pulls him into another room and they escape. And so it begins, a chase unlike any other. Langdon and Sienna are on the run, but they don't know who is on their heels or why they are in someone's sights. From past experience, Langdon should have considered a secret organization plot, but then he was having memory problems.

|

| La Mappa dell’Inferno by Sandro Botticelli |

In this case, it is Sandro Botticelli's La Mappa dell’ Inferno (The Map of Hell), one of the more frightening visions of the afterlife ever created. As Langdon looks at it closely, he sees that there have been some alterations in the artwork and he sees things that have also been manifesting in his recent nightmares of white-haired women, blood-red rivers and the stench of death. There is also the image of a plague mask, a uniquely shaped mask with a long beak. Doctors treating plague victims, who felt the long beak kept the pestilence from reaching their nostrils, wore it. The disease also known as The Black Death killed about a third of the population in the 14th century.

This piece of artwork was a tribute to the work that has become one of the world's most celebrated writings, Dante's Inferno, which presents the poet's macabre vision of his trip through the nine levels of hell that had tortures for specific types of sins. The painting reveals a subterranean funnel of suffering with fire, brimstone and sewage, with Satan himself waiting at the bottom.

This piece of artwork was a tribute to the work that has become one of the world's most celebrated writings, Dante's Inferno, which presents the poet's macabre vision of his trip through the nine levels of hell that had tortures for specific types of sins. The painting reveals a subterranean funnel of suffering with fire, brimstone and sewage, with Satan himself waiting at the bottom. The inspection of the image is interrupted by the squeal of tires and sirens, as police cars pull up and what appears to be an armed squad of soldiers with death or capture on their minds thunder up the stairs. Langdon and Sienna flee out the back way, thinking that the US government is after them as well.

The inspection of the image is interrupted by the squeal of tires and sirens, as police cars pull up and what appears to be an armed squad of soldiers with death or capture on their minds thunder up the stairs. Langdon and Sienna flee out the back way, thinking that the US government is after them as well. |

| Porta Romana |

Sienna's asset is a mind of incredible genius that it has set her apart from all her peers most of her life; but she lacks the art education to help Langdon.

The one thought that comes to Langdon's mind is that what he had been saying during that nightmare was "Vasari," not "very sorry," and he had to have been referring to Giorgio Vasari, an Italian painter and architect who has painted a mural at the Palazzo Vecchio. The twosome head there, and on the way Robert catches a glimpse of the white-haired woman from his dreams.

The one thought that comes to Langdon's mind is that what he had been saying during that nightmare was "Vasari," not "very sorry," and he had to have been referring to Giorgio Vasari, an Italian painter and architect who has painted a mural at the Palazzo Vecchio. The twosome head there, and on the way Robert catches a glimpse of the white-haired woman from his dreams. |

| Museo Casa di Dante |

Sneaking out through the Buontalenti Grotto, they dash into the Palazzo Vecchio where they hasten to the Hall of Five Hundred and then escape through the Hall of Geographical Maps.

Now there comes a charge through Robert's mind, with memories and revelations hitting him like jolts of electricity.

|

| Hall of Maps |

They spring to the Museo Casa di Dante that leads to Chiesa di Santa Margherita de' Cerchi and, finally, they dart to the Baptistery of San Giovanni, with doors by Ghiberti, where they find Dante's death mask, in which there are clues that lead them to Venice and Saint Mark's Square.

They spring to the Museo Casa di Dante that leads to Chiesa di Santa Margherita de' Cerchi and, finally, they dart to the Baptistery of San Giovanni, with doors by Ghiberti, where they find Dante's death mask, in which there are clues that lead them to Venice and Saint Mark's Square.Are you tired yet? This is the first rest the two have had. I needed a rest for sure! I took one.

|

| San Giovanni |

To Zobrist, the main problem facing the world today is overpopulation. Zobrist claimed that he felt trapped on a ship where the passengers doubled every hour in geometric progression, while he tried desperately to build a lifeboat before the ship sunk under its own weight. He advocated throwing half of the people overboard. He felt the 14th-century bubonic plague was a boon to society, which was more healthy, wealthy and wise after the population was decimated––and this is what led to the Renaissance. He pushed for a similar drastic solution. Dr. Elizabeth Sinskey, the head of the World Health Organization, expects the worst. Of course, the reader accepts that the paths of Langdon and Sienna's two searches are bound to intersect.

|

| Doge's Palace, Venice |

Meanwhile, the intrepid pair find a clue at The Horses of Saint Mark, speed through Doge's Palace in Venice and finally scurry to some of Dante's favorite places––like the Baptistery of San Giovanni where Dante was baptized––which leads to St. Mark's Chiesa d'Oro, where Dante met his lifelong love, Beatrice, and where Langdon and Sienna gain additional insights.

The trail leads now 1,000 miles to Istanbul, and they fly (hope they serve nuts on the plane; they haven't eaten for a long time) to the crossroads of Europe and, lastly, they race to the Hagia Sophia, the eighth wonder of the world, an amalgamation of Christian and Islamic art and architecture. I have to stop here before I completely spoil the mystery.

|

| Hagia Sophia |

Readers who gravitate to codes and symbols will enjoy parts of Brown's Inferno. Firenzophiles will appreciate the travelogue, and history enthusiasts will learn a lot.

It seemed that whenever the plot got thin or repetitive, Brown tried to dazzle his audience with art, architecture and historical name-dropping. But as with other books from Dan Brown, I had to think and was left pondering the following from Dante’s Inferno: The darkest places in hell are reserved for those who maintain their neutrality in times of moral crisis.

What would I be willing to do to save humanity? Something to mull over in these hot-as-Hades days.