|

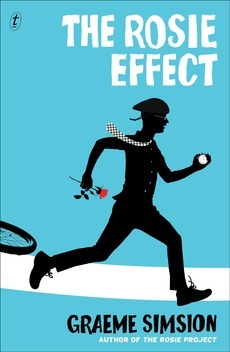

| UK cover on the left, US on the right. As usual, the UK cover is lots better |

It's 1964, and young Barbara Parker decides that winning Miss Blackpool would doom her to a year of dreary local ribbon-cutting ceremonies, much too long to wait to go to London to make her fortune. So she refuses the tiara and heads off, hoping to emulate her idol, Lucille Ball. In fairly short order, she wins the lead in a BBC sitcom called Barbara (and Jim), about a young couple's married life. Hornby takes Barbara (screen-named Sophie Straw) and the creative characters behind the show through their personal comedies and tragedies, all the way up until the present.

I'm reading that the book includes a mix of real history and fiction, and has a selection of black-and-white photographs that lend it a little of the feel of a sort of celebrity bio or TV history. Word also is that it's both hilarious and touching, as the characters experience sudden celebrity and what happens after.

Another character looks back on a long and eventful life in Alison Jean Lester's Lillian on Life (Putnam Adult, January 13). Even though I claim to be cynical about authors' blurbs, I have to admit that this first caught my eye when one of my favorite authors, Kate Atkinson, wrote: "I absolutely loved Lillian on Life. It was a delight . . . so fresh and clever."

In this debut novel, Lillian is born to a stereotypical staid midwestern family in the 1930s, but leaves convention behind, as she samples men and cultures around the country and the world. I like the idea that the story isn't told as a straight chronology, but as a series of 24 life lessons, told with wry humor and a determination to avoid regret. I'm not at all sure I'll like Lillian, but I do like character studies and she definitely looks like quite a character.

Speaking of characters, how about the late columnist Dorothy Parker? I was recently reading the book Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair (Penguin, October 2014) and giggling over her "Hate Songs" pieces on men, actresses, relatives and the office. That put me in the mood for more.

Author Ellen Meister decided that Dorothy Parker should never die, so she decided to imagine that Parker lives on, as a feisty ghost residing at her old drinking and

rapier-wit-wielding place, the Algonquin Hotel. Book One was 2013's Farewell, Dorothy Parker. But it wasn't a farewell, because the ghost of Dorothy Parker will return in Dorothy Parker Drank Here (Putnam Adult, February 24).

Author Ellen Meister decided that Dorothy Parker should never die, so she decided to imagine that Parker lives on, as a feisty ghost residing at her old drinking and

rapier-wit-wielding place, the Algonquin Hotel. Book One was 2013's Farewell, Dorothy Parker. But it wasn't a farewell, because the ghost of Dorothy Parker will return in Dorothy Parker Drank Here (Putnam Adult, February 24).This time around, Dorothy will buttonhole Algonquin resident Ted Shriver, who is a reclusive resident waiting to die of cancer, which he refuses to have treated. Shriver has no will to live since his brilliant writing career was derailed years before by a charge of plagiarism. Dorothy will team up with TV producer Norah Wolfe to try to keep Shriver among the living. I've only seen one early review, but it says the book is full of heart, wit, suspense and compassion, so it seems like just the ticket for a gloomy midwinter day.

And speaking of characters who drink––a lot––Stewart O'Nan's West of Sunset (Viking Adult, January 13) takes on F. Scott Fitzgerald during the last three years of his life. His career was decrepit, Fitzgerald had ruined his health, Zelda was in a sanitarium, and in 1937 he grabbed one last chance by heading to Hollywood to be a screenwriter.

The Hollywood studios in the late 1930s and early 1940s produced some of my very favorite films (The Philadelphia Story, Holiday, The Wizard of Oz, Gone With the Wind, Rebecca), which means that I'm anxious to read this even though I've never been much of a Fitzgerald fan. Still, advance reviewers say it's an insightful novelization of the waning years of Fitzgerald's life, which were nothing like the Jazz Age period. And if I also get to read about Louis B. Mayer, Humphrey Bogart and––hey!––even Dorothy Parker in La-La Land, I'm happy.

I have some trepidation about Laurie R. King's 13th Mary Russell/Sherlock Holmes book, Dreaming Spies (Bantam, February 24). I practically hurled the 11th book in the series, Pirate King, across the room in sheer frustration. Holmes was barely a presence, and Mary on her own was so boring, with her complaining and humorless self-satisfaction that I decided that was the end of my reading in the series. But I have some friends who said the next book, Garment of Shadows, was much better. What pushes me toward wanting to read this one is that the title is a play on Matthew Arnold's reference to Oxford as a city of "dreaming spires." I'm a complete sucker for Oxford-based mysteries.

I have some trepidation about Laurie R. King's 13th Mary Russell/Sherlock Holmes book, Dreaming Spies (Bantam, February 24). I practically hurled the 11th book in the series, Pirate King, across the room in sheer frustration. Holmes was barely a presence, and Mary on her own was so boring, with her complaining and humorless self-satisfaction that I decided that was the end of my reading in the series. But I have some friends who said the next book, Garment of Shadows, was much better. What pushes me toward wanting to read this one is that the title is a play on Matthew Arnold's reference to Oxford as a city of "dreaming spires." I'm a complete sucker for Oxford-based mysteries.The story of Dreaming Spies is apparently set not only in Oxford, but also in Japan. This visit to Japan is alluded to in a couple of earlier books, but this is the first time readers will learn exactly what Russell and Holmes got up to in that faraway land in 1924. Word is that it involves a blackmailing English lord and ninjas. Yes, ninjas. Will this 13th story in the series be a lucky 13? The proof will be in the reading.

One of my favorite Golden Age mysteries is Delano Ames's She Shall Have Murder, the first in a delightful series featuring Jane and Dagobert Brown, who are a sort of English Nick and Nora Charles. Compared to the Charleses, the Browns drink fewer martinis and more tea, but they get up to just as much silliness. In this first book, Jane Hamish is not yet married and is working in one of those classic English village law offices, where all the law you need to know is in the head of the senior partner, and the tea cart will be coming around any minute.

When spinster client Mrs. Robjohn is found dead from a gas leak in her home, the underemployed Dagobert Brown, Jane's intended, refuses to believe it's an accident and decides to investigate, dragooning a reluctant Jane into his sleuthing. It's a delightful story, with its charming characters and evocative description of the austerity of Britain shortly after World War II.

Delightful as the story is, why am I mentioning this old chestnut in the context of a book preview? Simple. Manor Minor Press has just republished the book with new cover art and annotations that add depth to the story. For example, I now know what Veganins and Melachrinos are, along with the full explanation of that British Double Summer Time I've seen mentioned in so many period British mysteries.

Another protagonist who is equal parts entertaining and exasperating is Don Tillman, first met in Graeme Simsion's The Rosie Project, which I reviewed here. Don is an Australian genetics professor who resembles The Big Bang Theory's Sheldon Cooper, only with a lot more interest in sex. In The Rosie Project, Don's Wife Project, in which he attempts to find a mate via a rigorously designed requirements questionnaire, becomes tangled up in the Father Project, wherein he agrees to help barmaid/student Rosie identify her biological father.

Another protagonist who is equal parts entertaining and exasperating is Don Tillman, first met in Graeme Simsion's The Rosie Project, which I reviewed here. Don is an Australian genetics professor who resembles The Big Bang Theory's Sheldon Cooper, only with a lot more interest in sex. In The Rosie Project, Don's Wife Project, in which he attempts to find a mate via a rigorously designed requirements questionnaire, becomes tangled up in the Father Project, wherein he agrees to help barmaid/student Rosie identify her biological father.I don't want to spoil The Rosie Project for you, but in the upcoming The Rosie Effect (Simon & Schuster, December 30), Don and Rosie are married and have moved to New York, where he is a visiting professor at Columbia and she is a medical student. Don has loosened up some of his strict rules for living to accommodate the more spontaneous and flexible Rosie, since he has concluded that, despite her failure to achieve a passing grade on his Wife Project questionnaire, she is the world's most perfect woman.

But when Rosie announces she is pregnant, Don is knocked for a loop. The amount of research involved in optimal pregnancy diet and exercise, successful parenthood and the best infant equipment is daunting enough, but a series of calamities result when Rosie repeatedly fails to be a cooperative subject and the rest of the world just doesn't get Don's spirit of scientific inquiry, as when he decides to spend long periods of time on a park bench observing small children in a playground and making notes.

I had the opportunity to read an advance copy of The Rosie Effect and, while it has a little of the bloat you always seem to see in the sequel to a runaway best-seller, and it doesn't achieve the same heights of inspired lunacy as The Rosie Project, it still gave me a few chuckles. It might be something that would cheer you up if you're a little under the weather after New Year's Eve.

Is it appropriate to look forward to a new book in a series when I still haven't read the first one? I was so excited about William Shaw's She's Leaving Home last year (originally published in the UK as A Song from Dead Lips) that I bought it right away, but it's still there on my e-reader. I find that's the problem with e-books; too easy to lose track of them.

Is it appropriate to look forward to a new book in a series when I still haven't read the first one? I was so excited about William Shaw's She's Leaving Home last year (originally published in the UK as A Song from Dead Lips) that I bought it right away, but it's still there on my e-reader. I find that's the problem with e-books; too easy to lose track of them.Shaw's series features Detective Sergeant Cathal Breen and temporary Detective Constable Helen Tozer of London's Metropolitan Police in the Swinging 60s. It wasn't all rock-and-roll and miniskirts. The force was openly sexist and racist, and there were plenty of bent coppers. Crime rates were high; fraud and corruption were more the rule than the exception.

Life on the force can be hard for Breen, with his Irish heritage, and far harder for Helen. In Kings of London (Mulholland, January 27), Breen finds a death threat in his work pigeonhole and is met with indifference about the finding of a mutilated body thought to be a homeless man. The interest level changes when another body is found, this time the son of a powerful politician. The politician wants results, but the prominent don't want any publicity that could possibly harm them.

The more I look at the reviews of the books in this series, the harder I shake my head at my failure to read the first book yet. This looks like a gritty, stylish rendering of a past that's not so distant but is still a different world.

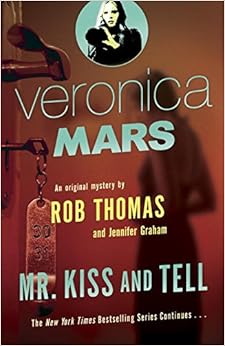

If you're a regular reader of Read Me Deadly, you know that I just love everything Veronica Mars. The TV show, the movie, and the book The Thousand-Dollar Tan Line that came out earlier this year. I'm even a devotée of the commercials that Kristen Bell is doing with her real-life husband, actor Dax Shepard, for Samsung. Check out their cute and funny Christmas ad here.

If you're a regular reader of Read Me Deadly, you know that I just love everything Veronica Mars. The TV show, the movie, and the book The Thousand-Dollar Tan Line that came out earlier this year. I'm even a devotée of the commercials that Kristen Bell is doing with her real-life husband, actor Dax Shepard, for Samsung. Check out their cute and funny Christmas ad here.Veronica will be sleuthing again in Rob Thomas's Mr. Kiss and Tell (Vintage Paperback Original, January 20). As fans know, the Neptune Grand hotel has been the scene of all manner of sins, from adultery to blackmail to murder. For the fanciest hotel in town, it sure has its seamy side!

Now, a woman complains that she was brutally assaulted in the hotel, smuggled out and dumped in a field, left for dead. The hotel hires Mars Investigations (i.e., Veronica, her father Keith, and their electronics savant, Mac) to investigate the woman's story. But the hotel isn't a terribly cooperative client; they refuse to turn over their reservation list, for example. Surveillance video has key gaps, the victim refuses to identify who she was supposed to meet at the hotel, and other witnesses seem to be hiding information too.

Now, a woman complains that she was brutally assaulted in the hotel, smuggled out and dumped in a field, left for dead. The hotel hires Mars Investigations (i.e., Veronica, her father Keith, and their electronics savant, Mac) to investigate the woman's story. But the hotel isn't a terribly cooperative client; they refuse to turn over their reservation list, for example. Surveillance video has key gaps, the victim refuses to identify who she was supposed to meet at the hotel, and other witnesses seem to be hiding information too.One of the strengths of the Veronica Mars world is its clear-eyed gaze on corruption in a town with a wide gap between rich and poor. The police force is usually responsive only to the powerful, and it takes Mars Investigations and its few allies in the force and the courts to get any form of justice. Early readers say that Veronica's usual cynicism about Neptune is in full force and that we see plenty of our other favorite characters, including Veronica's old biker buddy Weevil and love interest Logan. This looks like just what I'll need in the bleak midwinter.

Note: I received free review copies of The Rosie Effect and She Shall Have Murder.