During World War II, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered the new Special Operations Executive to "set Europe ablaze" by supporting the resistance to the Nazis in occupied countries. Many young men and women who knew other languages, especially French, were sent behind enemy lines to gather intelligence and work with local resistance groups. Their chances of being captured, tortured, imprisoned and executed were very high––and they knew it from the start.

For years, I've been fascinated by the story of the SOE, and especially of the young women who volunteered for this lethally dangerous duty. In an era when it was rare for a woman to do anything other than graduate from school to marriage and children, these women were trained in the arcana of espionage, including parachute jumping, hand-to-hand combat and silent killing. What was in the minds and hearts of the women who became SOE agents?

In Trapeze (Other Press, 2012), which is the predecessor to Tightrope, Simon Mawer gives us the story of a fictionalized SOE agent named Marian Sutro. She's English and French, grew up in Switzerland and moved to England with her family as things got dangerous on the European continent before World War II broke out. She had friends in France, especially Clément, the young scientist whom she'd had a crush on for years. When Germany overran France, it seemed very black and white to her; a place and people she loved were in danger from an evil invader and she wanted to help.

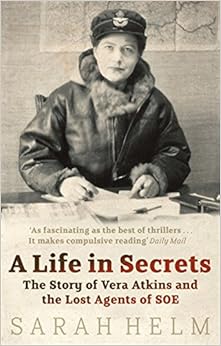

In Trapeze (Other Press, 2012), which is the predecessor to Tightrope, Simon Mawer gives us the story of a fictionalized SOE agent named Marian Sutro. She's English and French, grew up in Switzerland and moved to England with her family as things got dangerous on the European continent before World War II broke out. She had friends in France, especially Clément, the young scientist whom she'd had a crush on for years. When Germany overran France, it seemed very black and white to her; a place and people she loved were in danger from an evil invader and she wanted to help. When Tightrope begins, the war is in its last weeks and Marian is coming home. She wasn't an SOE agent in France for long. She was betrayed, captured by the Nazis, tortured and finally sent to Ravensbrück, the notorious prison camp for women near Berlin, where many real-life SOE female agents were sent. (By the way, I highly recommend Sarah Helm's masterful history of the camp: Ravensbrück: Life and Death in Hitler's Concentration Camp for Women (Nan A. Talese, 2015).)

When Tightrope begins, the war is in its last weeks and Marian is coming home. She wasn't an SOE agent in France for long. She was betrayed, captured by the Nazis, tortured and finally sent to Ravensbrück, the notorious prison camp for women near Berlin, where many real-life SOE female agents were sent. (By the way, I highly recommend Sarah Helm's masterful history of the camp: Ravensbrück: Life and Death in Hitler's Concentration Camp for Women (Nan A. Talese, 2015).)Back home in England, nobody knows how to treat Marian and she hardly knows who she is and how she is to live in this postwar world. Mawer evocatively portrays Marian's numbness and alienation, the way she can more easily relate emotionally to her memories of her fellow Ravensbrück prisoners than to her own family and colleagues. To help her recover from her traumatic war experiences, Marian is advised to see a psychiatrist. She tells him that life in the camp appeared to be nothing but gray, but underneath the monochrome their lives were complex, with hierarchies, networks and groups. The way a prisoner made her way through the complex meant the difference between life and death.

|

| Queueing for rationed food in 1947 |

Marian is offered a job and she attempts to return to some semblance of a normal life, but her past keeps impinging on the present. She has friends who are nuclear scientists, she has contacts in the intelligence services and, when she returns to Ravensbrück to testify against Nazi prison camp guards, she meets others who are in the intelligence game.

After the US drops atomic bombs on Japan, develops the far more powerful hydrogen bomb and seems to be seriously considering a preemptive strike on the Soviet Union, she wonders what was the point of all the sacrifice only a few years before, if World War III is now on the doorstep. Slowly, inexorably, Marian is drawn back into the ambiguous world of intelligence, with its agents, counter-agents, double agents and moles. Marian is once again in an environment where security and life itself depend on hierarchies, networks and groups. Will her choices lead to safety or betrayal?

After the US drops atomic bombs on Japan, develops the far more powerful hydrogen bomb and seems to be seriously considering a preemptive strike on the Soviet Union, she wonders what was the point of all the sacrifice only a few years before, if World War III is now on the doorstep. Slowly, inexorably, Marian is drawn back into the ambiguous world of intelligence, with its agents, counter-agents, double agents and moles. Marian is once again in an environment where security and life itself depend on hierarchies, networks and groups. Will her choices lead to safety or betrayal?Although this is a long and slow-moving novel, and Marian is a difficult character, I was riveted. Mawer makes Marian completely believable, even if often not very likable, and he immerses the reader in the tensions and uncertainty of her position, slowly upping the ante as the story goes on. Mawer has done his research, too, and skillfully interweaves real characters and events from SOE history, and British intelligence during the Cold War, into Marian's story. Details of Marian's SOE experiences will ring true to those who have read the histories. Her experiences reminded me a good deal of the description of what happened to SOE agent Eileen Nearne, which you can read about in brief here.

|

| Former SOE agents Eileen Nearne and Odette Sansom attend the 1993 unveiling of a plaque at Ravensbrück, where both were imprisoned |

|

| Hayley Atwell in Restless |

Although I did read Trapeze before reading Tightrope, I don't think that's at all necessary. Tightrope is also a better read than Trapeze, so if there's any question in your mind about whether you'd like either of them, I'd go with Tightrope first.

|

| Just in case you want to read more . . . |

Note: I received a free review copy of Tightrope from the publisher, through the Amazon Vine program. Versions of this review may appear on Amazon, Goodreads, BookLikes and other reviewing sites under my usernames there.