One of the rites of spring that I always enjoy is the opening day for Little League baseball and softball. My town begins the season with a parade down the main street, and while there are many more marching in the parade than there are watching, it it is fun to see such happy faces on the kids and their parents. Just the names of the teams––like River Bandits and Sand Gnats––are enough to lift the spirits. Hats off to all the Little League dads and moms who are great volunteers.

One of the rites of spring that I always enjoy is the opening day for Little League baseball and softball. My town begins the season with a parade down the main street, and while there are many more marching in the parade than there are watching, it it is fun to see such happy faces on the kids and their parents. Just the names of the teams––like River Bandits and Sand Gnats––are enough to lift the spirits. Hats off to all the Little League dads and moms who are great volunteers.Mothers and their influences have been a topic in my reading lately as well.

Will Schwalbe was working in the publishing world when his

mother received the grim diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Mary Anne Schwalbe had

always lead a very active life, which at this point in time revolved around the

treatment of refugees in war torn countries. It was not unusual for her to arrive

home in poor health, after having contacted some kind of infection from living

in poor sanitary conditions.

Will Schwalbe was working in the publishing world when his

mother received the grim diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Mary Anne Schwalbe had

always lead a very active life, which at this point in time revolved around the

treatment of refugees in war torn countries. It was not unusual for her to arrive

home in poor health, after having contacted some kind of infection from living

in poor sanitary conditions.This time, when she arrived home from Afghanistan in early 2007, she was obviously ill. Despite seeing doctors, it took several months to pinpoint the cause of her symptoms, as is often the case with this particular malignancy. When she was given her final diagnosis, her condition was too far advanced for surgery, and her hope was for successful chemotherapy to prolong her life––but not save it.

Mary Anne's family rallied around to keep her company during

the chemo infusion sessions that could last for hours. Will and his mother had always

enjoyed reading and talking about books, and these discussions now morphed into

a book club meant for two. There

was no particular pattern in their reading choices; one or the other would

mention a book they were reading or wanted to read and they both read it and

shared their thoughts about it.

Mary Anne's family rallied around to keep her company during

the chemo infusion sessions that could last for hours. Will and his mother had always

enjoyed reading and talking about books, and these discussions now morphed into

a book club meant for two. There

was no particular pattern in their reading choices; one or the other would

mention a book they were reading or wanted to read and they both read it and

shared their thoughts about it. The End of

Your Life Book Club (Knopf, 2012), written

by Will Schwalbe, is the chronicle of the last months of his mother's life and how reading eased her way through a difficult time.

The End of

Your Life Book Club (Knopf, 2012), written

by Will Schwalbe, is the chronicle of the last months of his mother's life and how reading eased her way through a difficult time. Over the course of the next year, this pair read books of

varied genres, from mysteries like Brat

Farrar to books with a psychological bent, such as John Kabat-Zinn's Full Catastrophe Living. Most of the

books seemed to fall into the category that exemplifies the triumph of the human

spirit over adversity, whether it was by cancer, imprisonment, war or other

deprivations. No subject was too forbidding, too depressing or too violent for Mary Anne.

Over the course of the next year, this pair read books of

varied genres, from mysteries like Brat

Farrar to books with a psychological bent, such as John Kabat-Zinn's Full Catastrophe Living. Most of the

books seemed to fall into the category that exemplifies the triumph of the human

spirit over adversity, whether it was by cancer, imprisonment, war or other

deprivations. No subject was too forbidding, too depressing or too violent for Mary Anne.Mary Anne did not like silly books, however. One of Mary Anne's peculiarities was that she always read the end of the book first and then started at the beginning. In this way, she could get through the difficult and horrifying parts of books because she already knew how everything turned out.

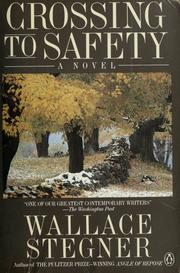

One of their favorites was Crossing to Safety, by Wallace Stegner, about the lifelong friendship of two couples, which was being changed because one of the women was dying of cancer. Another was The Savage Detectives, an ambitious novel by Roberto Bolaño, a Chilean poet and novelist, who died from liver disease before his book was translated to English. A book I would also like to read was Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, which is a narration by John Ames, an elderly preacher who has lived almost all of his life in Gilead, Iowa. He is writing a letter to his seven-year-old son, summing up the blessings of his life. Robinson writes the story as a meditation on fathers and children, particularly sons, on faith, and on the imperfections of man.

The Painted Veil, by W. Somerset Maugham, is another I added to my TBR. It is about the realization that finally comes to a self-absorbed young woman, that there are better goals in life for a woman than focusing on personal appearance and catching a mate.

Most of the books the pair read are covered cursorily in The End of Your Life Book Club, because the story is actually about the journey a son takes to become close to the mother who seemed at times to neglect her own children in her attempt to improve the lives of those children in other worlds of misery.

Mothers are a big influence in a person's life not only in the real world, but in fiction.

For Ellie Rush, the main protagonist in Naomi Hirahara's first of a new series, Murder on Bamboo Lane (Berkley, April 1, 2014), the problem is that she has been a big disappointment to her mother. Despite her mother's grand expectations, Ellie has joined the LAPD.

Ellie is half-white and half-Japanese, and she accepts the fact that she is never seen as white by whites or Japanese by the Japanese. Currently, just off probation, she has a very unglamorous job as a bicycle cop taking complaints, writing up tickets, and hearing more complaints.

While patrolling the porta-potty area during the Chinese New Year parade, Ellie is one of the first officers to come across a dead body in an

alley. She is dismayed to find that the experience much worse that she

thought it could be, and it was made more shocking by the fact that she

recognized the body as a girl she knew in college.

While patrolling the porta-potty area during the Chinese New Year parade, Ellie is one of the first officers to come across a dead body in an

alley. She is dismayed to find that the experience much worse that she

thought it could be, and it was made more shocking by the fact that she

recognized the body as a girl she knew in college.Ellie has the ambition to be a detective in the homicide division, and she doesn't mind taking on menial duties that will help her career. She eagerly helps the homicide detectives, who appreciate her inside information of the suspects in the case.

This case is one that will really test her loyalties, because

her friends now see her as one of "them." She has an aunt who holds a very high

position in the LAPD and who expects her help, but her co-workers resent her

assignment to the murder investigation.

This case is one that will really test her loyalties, because

her friends now see her as one of "them." She has an aunt who holds a very high

position in the LAPD and who expects her help, but her co-workers resent her

assignment to the murder investigation.This is an enjoyable story about a young woman at the beginning of her career who is torn over how to be a good friend as well as a good officer. She is also trying to be a good family member, but she still feels compelled to bring her pothead brother to task. Of course, in the end, Ellie's mom is beginning to take pride in her daughter's choices.

Naomi Hirahara is better known

for her Mas Arai series. Arai is a Los

Angeles gardener in his seventies who, as a boy, survived the atom bomb attack on

Hiroshima. Blood Hina is the fourth of this series, in which Arai is aging and financially

struggling, but the main problem in his life is that he is supposed to be best

man at the wedding of an old friend, Haruo, and Haruo's fiancée, Spoon. Arai takes his responsibilities quite

seriously. He has known Haruo for a long time and he bonded with him because they both survived Hiroshima, which left Haruo disfigured. Aside from fumbling and

losing the wedding ring in a koi pond, Mas foresees trouble in this new marriage, especially between Haruo and Spoon's daughter. His foreboding is

on the money because the wedding is called off when some Hina dolls are stolen

from Spoon's home and Haruo is blamed.

Naomi Hirahara is better known

for her Mas Arai series. Arai is a Los

Angeles gardener in his seventies who, as a boy, survived the atom bomb attack on

Hiroshima. Blood Hina is the fourth of this series, in which Arai is aging and financially

struggling, but the main problem in his life is that he is supposed to be best

man at the wedding of an old friend, Haruo, and Haruo's fiancée, Spoon. Arai takes his responsibilities quite

seriously. He has known Haruo for a long time and he bonded with him because they both survived Hiroshima, which left Haruo disfigured. Aside from fumbling and

losing the wedding ring in a koi pond, Mas foresees trouble in this new marriage, especially between Haruo and Spoon's daughter. His foreboding is

on the money because the wedding is called off when some Hina dolls are stolen

from Spoon's home and Haruo is blamed. What drew me to this mystery is that it revolves around

some old and interesting Japanese customs. Rather than celebrating mothers and

fathers in a festival, they honor children.

What drew me to this mystery is that it revolves around

some old and interesting Japanese customs. Rather than celebrating mothers and

fathers in a festival, they honor children. Girl's Day is a special day in Japan, celebrated on March

3, the third day of the third month. It is called Hinamaturi and it is also known as Doll's Day because the tradition of displaying Hina dolls on a tiered

stand, covered by a red carpet, at the top of which are the Emperor and Empress.

Girl's Day is a special day in Japan, celebrated on March

3, the third day of the third month. It is called Hinamaturi and it is also known as Doll's Day because the tradition of displaying Hina dolls on a tiered

stand, covered by a red carpet, at the top of which are the Emperor and Empress. It is some of these sometimes quite valuable dolls that are missing in Blood Hina, and Mas

Arai knows he has to find them if his friend Haruo is to be happy. Arai must

juggle his amateur sleuthing with the demands of multiple gardening clients

while trying to solve a few murders at the same time.

It is some of these sometimes quite valuable dolls that are missing in Blood Hina, and Mas

Arai knows he has to find them if his friend Haruo is to be happy. Arai must

juggle his amateur sleuthing with the demands of multiple gardening clients

while trying to solve a few murders at the same time. May 5 is Boy's Day in Japan, and it always falls on the fifth

day of the fifth month. Also known as the Feast of Banners, it is celebrated by

banners symbolizing the family. One of the themes for the day is that of respect for the individual personalities of children.

May 5 is Boy's Day in Japan, and it always falls on the fifth

day of the fifth month. Also known as the Feast of Banners, it is celebrated by

banners symbolizing the family. One of the themes for the day is that of respect for the individual personalities of children.In 1948, the government decreed this day to be a national holiday called Children's Day. It celebrates the happiness of all children and expresses gratitude to mothers.