Then We Take Berlin

Then We Take Berlin, by John Lawton

(Atlantic Monthly Press; September 3, 2013)

John Lawton is on my top-five list of contemporary authors, so I was excited when I heard he had created a new protagonist, John Wilfrid Holderness. That sounds like a posh name, but he's known by most people as Joe Wilderness––a much better fit to this character.

Joe is a London East End wide boy, a chancer who lives on his wits and guile. That's all the more true when his mother is killed in the Blitz, found dead, ensconced on a barstool with her gin still sitting in front of her. Joe's grandfather, Abner, moves Joe into an attic room at his place in Whitechapel, where Abner lives with his longtime girlfriend (and sometime prostitute), Merle. (Not that her name really is Merle, but that's a good Hollywood-sounding sobriquet for when she's on the game.)

Abner teaches Joe everything he knows about burglary and safe-cracking. Joe is a quick study, not just about crime, but about books, and observing people. Smart and lucky are two different things, though. Just when all the soldiers and sailors are returning home from World War II, Joe is drafted. He's about to be tossed into the punishment cells for insubordination (that's a mild name for it) during his basic training, when he's plucked out by Lieutenant Colonel Burne-Jones, who's seen Joe's IQ score. Burne-Jones sends Joe to Cambridge to learn Russian and German, and to London for individual tutoring in languages, politics and history.

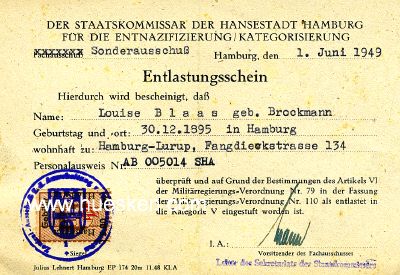

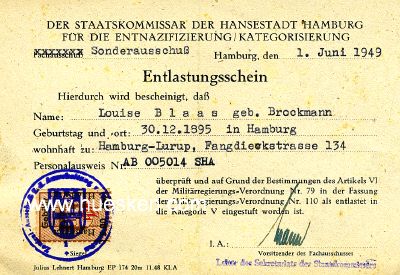

Of course, Burne-Jones is training Joe to work in military intelligence, but you already figured that out. Off Joe goes to Berlin in 1946, where his job is to assess German citizens looking to get jobs in the de-Nazified country. To qualify, Germans had to fill out a form the Germans nicknamed

Fragebogen, the Questions. Intelligence officers like Joe quizzed candidates over their answers to determine whether they would qualify for the prized

Entlastungsschein––which the Germans called

Persilschein, after Persil laundry detergent––the whiter-than-white document that proved that you're not considered an enemy or a threat.

Aside from that dull desk job, though, what an amazing time and place for a wide boy. "It was love at first sight. He and Berlin were made for each other. He took to it like a rat to a sewer." In between intelligence jobs for Burne-Jones, Joe can't resist becoming a black market seller, then increasing the stakes in his black market game, which means making ever larger and more dangerous deals; deals that involve bent Russians and dangerous crossings to the Russian sector.

But for Joe, it's not all about sussing out former Nazi bigwigs and scientists by day, and smuggling by night. At one of Berlin's nightclubs––famous in the Weimar era for using tabletop telephones and pneumatic tubes so that strangers could propose assignations––Joe meets Christina Helene von Raeder Burckhardt, known by the Brits and Yanks as Nell Breakheart. Not because she actually breaks hearts, but because she's so beautiful, inside and out, that they're lining up in hopes of getting their hearts broken. And wouldn't you know, she chooses Joe.

|

Yes, Joe's quip is about Hitler, who was a

Corporal in the First World War |

I can't blame Nell. Joe's got that bad-boy fascination and I wanted to hang around with him for the snappy patter alone. In one of my favorite scenes, he is introduced to Nell's old friend Werner, who's no fan of the occupying forces. Werner sneers, "I do not care to sit down with the Allies, Herr Corporal." Joe answers: "Now don't you go bashin' corporals. We may be a bunch of numskulls but some of us go on to run empires that last a thousand years."

|

| Trümmerfrauen clearing rubble |

In language so vivid the scenes unreel like a half-remembered film, Lawton recreates postwar Berlin, with its ruined buildings, squalid living quarters created in cellars or apartments with shorn-off walls, crews of women who earn rations by clearing rubble in bucket lines, dirty kids harassing occupation forces servicemen for candy bars, the stink of open sewers, fear and despair, and the sweeter scents of money, graft and opportunity. I read a ton of World War II historical novels and I can't think of another one that does it with more verve.

|

| JFK in Berlin |

But the novel isn't all postwar Berlin. The bombed-out Berlin tale is bookended by the stories of Joe and Nell in the summer of 1963. You know, the summer JFK made his famous visit to Berlin. If there is some of the 1963 plot that is not quite up to snuff (and, admittedly, there is), that takes up a very small proportion of what is a dazzlingly inventive and layered story, packed with fully dimensional characters–––several of whom Lawton fans will recognize from Lawton's series of Frederick Troy novels.

I've often wondered why John Lawton hasn't gained the recognition I firmly believe he deserves. I've come to think it might be because of the book world's compulsion to categorize books and authors into easy genres and sub-genres. Lawton's books are most often classified as mystery and espionage, but neither is accurate. As Lawton once commented, they are "historical, political thrillers with a big splash of romance, wrapped up in a coat of noir." The noir comes in because, as you might have suspected, reading about Joe Wilderness, John Lawton likes to write about people on the edge, living in a world of shadowy morality. Lawton says, "I don't think there are unequivocal good guys. If there are, then they're teetering on the edge, and it's the edge, the ambivalence, that I like about espionage and spooks." Me too.

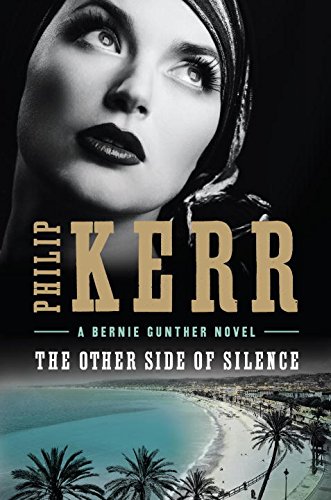

If you enjoy authors like Ian McEwan, Philip Kerr, Sebastian Faulks and William Boyd, give this book a try, along with his other novels, especially his haunting 2011 title,

A Lily of the Field.

Note: I received a free review e-galley of

Then We Take Berlin from NetGalley––but I loved it so much I ordered the hardcover as soon as I finished reading the galley. Versions of this review may appear on Amazon, Goodreads and other reviewing sites under my usernames there.

This is another one of Kerr’s dual-narrative novels, which he’s done a few times with Bernie. It starts in 1956, with Bernie working as a hotel concierge on the French Riviera. Because of his World War II misadventures as a reluctant aide to some big-time Nazi war criminals, he’s living under the false name Walter Wolf. The other narrative, which takes up only a couple of chapters, flashes back to 1945 Königsberg, East Prussia, when Bernie was in the German army, falling in love with a young radio operator while the Russian army encircled the city.

This is another one of Kerr’s dual-narrative novels, which he’s done a few times with Bernie. It starts in 1956, with Bernie working as a hotel concierge on the French Riviera. Because of his World War II misadventures as a reluctant aide to some big-time Nazi war criminals, he’s living under the false name Walter Wolf. The other narrative, which takes up only a couple of chapters, flashes back to 1945 Königsberg, East Prussia, when Bernie was in the German army, falling in love with a young radio operator while the Russian army encircled the city.