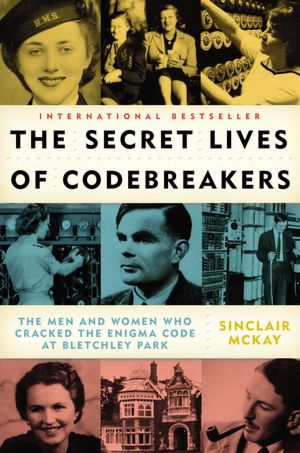

The Secret Life of Codebreakers: The Men and Women Who Cracked the Enigma Code at Bletchley Park by Sinclair McKay

The Secret Life of Codebreakers: The Men and Women Who Cracked the Enigma Code at Bletchley Park by Sinclair McKayImagine being a member of a team whose work was said to have shortened World War II by at least two years––and not being able to tell anybody about it for decades. Your friends, neighbors and family may even have thought you were a coward who failed to join up and fight for your country. That's exactly the position of the 10,000-plus men and women who worked at England's Bletchley Park to crack the codes used by the Axis powers during the war. They were summoned to Buckinghamshire with no disclosure of the reason for the summons and were required to sign the Official Secrets Act almost as they arrived.

It wasn't until over 30 years later that the requirement of silence was lifted. During all those years, unlike other wartime groups, Bletchley Park's personnel had no reunions and were deprived of the chance to sit and reminisce with old colleagues. By the time they could share their stories with their families, most of their parents had died.

Much has been written about how Germany's Enigma code was broken at Bletchley Park––or BP, as it was often called––but Sinclair McKay's principal focus in this insightful book is the people there; who they were, their working and living conditions, and the social environment in this hothouse atmosphere. And what a grab-bag of personnel BP was. University dons, debutantes and inner-circle graduates of Eton and Harrow, Oxford and Cambridge worked alongside the working class––mostly young women––with little of the social stratification that normally typified British life. Because of their long working hours and strict secrecy, they had to entertain themselves in their off hours. And they did, with amateur theatricals, singing groups, dancing, films, tennis, hiking and chess and bridge games.

BP is best known as the place where Alan Turing and others developed the precursors of modern computers. Germany's Enigma encryption machine performed its encoding mechanically, and Turing's conviction was that decryption should be possible by using a machine. The "bombes," as they were called, that the BP team eventually developed were massive machines straight out of science fiction of the era, with electrical connections snaking all over, long strips of paper feeding through, and loud, rackety clacking noise as the bombes ran through thousands and thousands of possible decrypts.

But before Turing's machines came online––and even afterward––hard work and ingenuity cracked codes, even Enigma codes. The BP boffins were able to study some early Enigma machines, so they knew how they worked. They used that knowledge, together with insights about human nature, to come up with starting places for decryption.

The "Herivel Tip" was a way to increase the odds of figuring out that day's cipher key from an Enigma machine. The cipher key was a three- or four-letter combination on a rotor with multiple rings of letters, a little like a luggage lock. The cipher key was used to encrypt the plaintext message, and anyone who knew the cipher key could decrypt the encrypted message. Hut 6's John Herivel imagined that a hurried or lazy Enigma operator might not bother to lift the rotor out of the machine to spin the rings and reset the cipher key for the day. If the operator took the shortcut of changing the setting by just sticking a finger inside the machine and pushing the rings, that would limit how far a ring could rotate from the previous day's setting. Since the starting position of the rings before the reset was typed––unencrypted––in the first message sent for the day, this greatly narrowed down the possibilities for the current day's key and allowed the analyst to run through them all first.

Hervel's Tip wasn't the only insight into human nature that allowed codes to be cracked. Other BP personnel remembered to see the Enigma operators as humans with ordinary frailties too. The Abwehr's Enigma machine used a four-letter cipher key, so BP's personnel would start by trying out common four-letter curse words and names.

I got a particular kick out of reading about how Operation Double Cross helped in decryption. I recently read Ben Macintyre's excellent Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies, which describes the double agents used by British intelligence. Because British intelligence knew what these agents' reports to their German contacts said, when the reports reappeared in German encrypts, they were readily decrypted, thus revealing that day's cipher key.

McKay is at his best when describing how BP's personnel applied their brain power and quirky styles of thinking to their formidable task. BP just gathered a group of academics, bright people from the various armed services, and civilians with language and other skills (like being particularly good at the Times cryptic crossword puzzle) and told them to get on with it. Despite the many privations, most recall it as the time of their lives, and nothing afterward ever quite touched the level of the experience. McKay isn't quite as good at bringing to life the BP personnel in their off hours, but reading about the human context of the work at BP makes this book a valuable reading experience for anyone who enjoys World War II social history.

The Secret Life of Codebreakers will be published by Plume (a division of Penguin Group USA) on September 25, 2012. It was published in the UK last year under the title The Secret Life of Bletchley Park: The WWII Codebreaking Centre and the Men and Women Who Worked There.

Note: I received a free advance reading copy of this book for review. Versions of this review appear (or may appear in the future) on Amazon and Lunch.com under my usernames there.