What do you do when you fall into bed exhausted and then can't get to sleep? After rejecting ideas too masochistic (scouring out the bathtub, ironing) and even worse (lying there and making a mental list of where you've gone wrong since first grade, pondering our current US Congress), you should reach for a book or a DVD and the remote. Which one all depends on how you feel.

|

| Morgan Freeman and Tim Robbins |

If work has you feeling imprisoned and you've got a life sentence with those in bed beside you: your spouse, snoring and snorting in his sleep, and your dog, who won't stop licking his privates: Break out with George Clooney in

O, Brother, Where Art Thou?, if you're hankering for a Coen brothers movie with bluegrass music, or

Out of Sight, if you're more in the mood for an escaped Clooney pining after Jennifer Lopez, who plays a dedicated US marshal in a movie based on the Elmore Leonard novel. Perhaps you like the idea of the prison being a World War II German POW camp, and your thoughts about the escapee run to the more the merrier, and include Steve McQueen on a motorcycle; if so, fire up

The Great Escape. You could watch a cult favorite,

The Shawshawk Redemption, featuring unconventional prisoner Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins), and his buddy, the prisoner/entrepreneur, Red (Morgan Freeman).

Or, crack open Michael Robotham's

Life or Death (Mulholland, March 2015), for a look at another enigmatic prisoner, Audie Palmer, who climbs out of a Texas prison the night before he's due to be paroled. Audie had admitted his involvement in an armored truck robbery that led to the deaths of four people. He was sentenced to 10 years, but the missing $7 million was never recovered. Weaving in and out with Audie's back story are the efforts to find him by pint-size FBI Special Agent Desiree Furness; the sheriff, who as a deputy shot Audie in the head during the robbery; and a prison buddy named Moss. Aussie author Robotham's storytelling kept me turning pages, but some British substitutions for their American counterparts (such as bank "queue" rather than "line") were a little distracting. More distracting are the length of Audie's sentence (c'mon, this is Texas, not Scandinavia), the fact Audie even survived in the joint, given the particulars, and the ease with which he escaped; however, these quibbles weren't enough to keep me from enjoying it. This isn't one of those pulse-pounding thrillers; it's the kind that makes you want to know what happened in the past and how things would end, and, no, I didn't peek.

For when you're so tired, you're feeling less than human––in fact, you're wondering if you're lower on the mammal totem pole than your dog: Empathize with Jax, a mechanical servitor who longs for freedom in Ian Tregillis's

The Mechanical (Orbit, March 2015), a hybrid of steampunk, fantasy, and alternate history set in the early 1900s. The book opens with the public execution of some Catholic spies and the destruction of a rogue mechanical man. In the 17th century, the work of scientist

Christiaan Huygens led to the development of a Dutch army of automata powered by alchemy and clockworks. These

"Clakkers," capable of independent thought, but enslaved through a built-in hierarchy of obligations

called "geasa" to their masters and the Queen on the Brasswork Throne, allowed the Netherlands to become the most powerful nation in the world.

There is now an uneasy truce between the Netherlands and the remnants of its opposition in New France (in Canada). In the capital of Marseilles-in-the-West,

spy-in-charge Berenice Charlotte de Mornay-Périgord has her hands full with a dangerous

Game of Thrones-like situation. Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, her small espionage network is disappearing. One of her spies,

Luuk Visser, a Catholic priest working undercover as a Protestant pastor, gives Jax an errand and then, oh man, you really must read this book for yourself. Everyone is passionate and scheming away like mad. I've never read anything quite like this cinematic novel, and I bet we'll see it eventually on the big screen. It tackles free will, what it means to be human, identity, loyalty, the meaning of faith and religious freedom, and revenge and redemption. Tregillis doesn't shy away from harming his characters, so you can't assume anyone is safe. Some people may find Berenice's foul mouth offensive, and there are a few scenes I found genuinely disturbing. Some scenes drag a little bit, but these flaws are minor. I'm glad there are two more coming in the Alchemy Wars trilogy because this book was great reading on a sleepless night.

If you'd rather watch a robot than read about one, there are the Terminator movies with our former California governator, Arnold Schwarzenegger, as a cyborg sent back from a future in which machines rule the world. I'm telling you, Schwarzenegger was born to play this role. Blade Runner, based on the Philip K. Dick novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

If you'd rather watch a robot than read about one, there are the Terminator movies with our former California governator, Arnold Schwarzenegger, as a cyborg sent back from a future in which machines rule the world. I'm telling you, Schwarzenegger was born to play this role. Blade Runner, based on the Philip K. Dick novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?,

features Harrison Ford as Los Angeles cop Rick Deckard, who is called back to duty in 2019 to track down and kill rogue replicants. James Cameron's Aliens has a cyborg on hand when Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver was born for this one) returns to the planet of Alien. Paul Verhoeven's 1987 movie,

Robocop (forget the re-make), is about a Detroit cop, killed in action, who returns to the force as half-human/half-robot. (And they say Humpty Dumpty couldn't be put back together again.) There are many more of these movies worthy of the time it takes to pop corn and wash it down with a Coke, such as the charming animated flick,

The Iron Giant;

Star Wars, Episode IV: A New Hope (thank goodness there's no Jar Jar Binks)....

Say you're in that half-asleep/half-awake state when your identity feels like a mirage, so you could really get into something to do with spies:

Say you're in that half-asleep/half-awake state when your identity feels like a mirage, so you could really get into something to do with spies: Of course, you can't go wrong with another viewing of

The Third Man, set in Allied-occupied Vienna and

starring Joseph Cotten as pulp western writer Holly Martins and Orson Welles as his childhood friend, Harry Lime. We could argue whether it's the best-ever espionage movie. In

Éric Rochant's 1994 film,

Les Patriotes (

The Patriots), Ariel Brenner (Yvan Attal) leaves his home in France for Israel on his 18th birthday. There, he joins Mossad and loses his idealism in a morally fuzzy world. Naval commander Tom Farrell (Kevin Costner) takes up with Susan Atwel (Sean Young), the mistress of US Secretary of Defense David Brice (Gene Hackman), in 1987's

No Way Out. Susan's murder cues the spinning of a web of deceit. This is a re-make of a terrific 1948 movie,

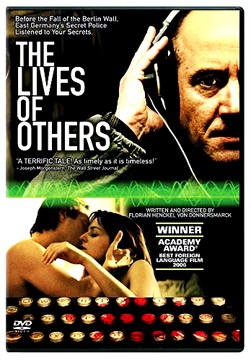

The Big Clock, with Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, and Maureen O'Sullivan. In the German movie,

The Lives of Others, it's 1984, and Stasi agent Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe) is compelled to launch an investigation of

the celebrated East German playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) by a man who has designs on Dreyman's girlfriend. Don't you love wheels within wheels?

Make sure you leave the butter off your popcorn if you decide to watch your spies on the page instead of on the screen. Don't waste time piddling around when you're tired; go straight to the British novels. What is it about MI5 and MI6 that makes seeing them under the microscope so diverting? We'll think about that while we cringe at some of these British writers' disdainful depictions of the CIA "cousins" as demanding and inept, throwing around cash, bigfooting joint operations, and screwing them up because they think about short-term payoffs rather than long-term consequences.

I kept a stiff upper lip about the cousins and enjoyed Charles Cumming's

A Colder War (St. Martin's Press, 2014). It's the second series book about Thomas Kell, an MI6 agent disgraced during the Witness X affair, whom we first met in the 2012 Steel Dagger winner,

A Foreign Country (see review

here). Kell has now once again been hauled out of the cold, this time to investigate the death of Paul Wallinger, head of the SIS station in Turkey, in an airplane crash. MI6's Amelia Levene thinks three recent intelligence disasters point to a mole in the SIS or the CIA.

Yeah, looking for a mole is nothing new, but Cumming does a good job with it. He takes his time; there are close to 400 pages. Notable are the clarity of the writing, use of locations, and the charm of the descriptions. It was a pleasure to learn what Tom is reading and to see what's on his shelves. Cumming once worked for MI6, and I liked his knowledge about how the agency works (the extent to which personal relationships affect spying is interesting) and his familiarity with spycraft. The life of a Cumming spy definitely isn't for everybody. Their careers ruin their family relationships and make keeping their stories straight––to themselves, as well as everyone else

––almost impossible. They are betrayed by ass-covering superiors and ambitious colleagues, and they need a good night's sleep and sweet dreams as much as anybody. At least a gorgeous young woman falls into bed with Tom, a lonely man in his mid-40s. You might roll your eyes at this, but, hey, while Tom's no James Bond, he's not John Gardner's cowardly Boysie Oakes of

The Liquidator fame, either. I'm looking forward to seeing Tom again on a night I can't sleep.

Danger Calling

Danger Calling Down Under

Down Under Rolling Stone

Rolling Stone