There's just something so very luxurious about shedding the day as well as my clothes, slipping into bed, and picking up a great book to be whisked away to a world outside my own. My husband may or may not be by my side, but my two dogs are definitely on the bed somewhere. On the bedside table, there's something to eat and drink, a heavy-duty flashlight (for under-the-covers use, and it doubles as a club if my reading conjures up a wild-eyed ax murderer lurking behind the closet door), and a bookmark for when I submit to "Nature's soft nurse," sleep.

But first, some books:

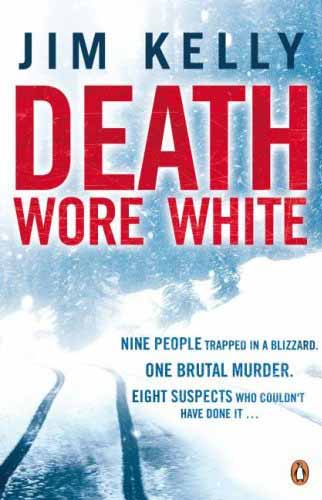

A warm bed is the best vantage spot for pondering Jim Kelly's version of a locked-room murder in the snow of West Norfolk, England. Death Wore White (2009) opens as Sarah Baker-Sibley, driving her Alfa Romeo, obeys a detour sign on the main coast road and follows tail lights onto the Siberia Belt, a narrow unpaved road. Half a mile away, Det. Inspector Peter Shaw and Det. Sgt. George Valentine are checking a report of toxic waste on frigid Ingol Beach when they discover a dead man on an inflatable raft floating into shore. The man's bloody mouth and a corresponding mark show that he has bitten his own arm to the bone.

A warm bed is the best vantage spot for pondering Jim Kelly's version of a locked-room murder in the snow of West Norfolk, England. Death Wore White (2009) opens as Sarah Baker-Sibley, driving her Alfa Romeo, obeys a detour sign on the main coast road and follows tail lights onto the Siberia Belt, a narrow unpaved road. Half a mile away, Det. Inspector Peter Shaw and Det. Sgt. George Valentine are checking a report of toxic waste on frigid Ingol Beach when they discover a dead man on an inflatable raft floating into shore. The man's bloody mouth and a corresponding mark show that he has bitten his own arm to the bone. When the two policemen make their way to the Siberia Belt, they find a line of eight vehicles stuck in the snow behind a pine tree that has fallen across the road. There is only one set of footprints leading to the pick-up that's first in line. The second vehicle's driver, Ms. Baker-Sibley, insists that the third vehicle's driver, who walked up to the pick-up's window for a brief conversation, kept his hands in his pockets the entire time. So who stabbed the pick-up's driver in the eye with a chisel? More forensic evidence makes this murder even more difficult to comprehend. Is it related to the corpse on the raft, and a body that's discovered in the sands later? As well as investigating these three murders, Peter looks into a cold case involving the murder of the Tessier boy. At that time, Peter's father, now dead, was George's partner, and the two cops made a mess out of the investigation. The senior Shaw retired, and George was demoted.

When the two policemen make their way to the Siberia Belt, they find a line of eight vehicles stuck in the snow behind a pine tree that has fallen across the road. There is only one set of footprints leading to the pick-up that's first in line. The second vehicle's driver, Ms. Baker-Sibley, insists that the third vehicle's driver, who walked up to the pick-up's window for a brief conversation, kept his hands in his pockets the entire time. So who stabbed the pick-up's driver in the eye with a chisel? More forensic evidence makes this murder even more difficult to comprehend. Is it related to the corpse on the raft, and a body that's discovered in the sands later? As well as investigating these three murders, Peter looks into a cold case involving the murder of the Tessier boy. At that time, Peter's father, now dead, was George's partner, and the two cops made a mess out of the investigation. The senior Shaw retired, and George was demoted.The less-than-warm relationship between current partners Peter and George is nothing new for experienced crime fiction readers, but the ingenious plot, the interpretation of the forensic evidence, and the vivid Norfolk setting and its hard-scrabbling inhabitants make this police procedural, first in the Shaw/Valentine series, worth losing sleep.

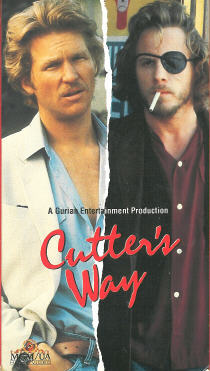

Oh man, there are no sweet dreams when the disillusionment of Vietnam comes home to America. In Newton Thornburg's Cutter and Bone (1976), Alex Cutter is a paranoid, scarred, and disabled Vietnam vet, and Richard Bone is a hedonistic dude, fond of drink and getting high, who abandons his family and advertising career to scrape by as a gigolo. (In the 1981 movie based on the book, Cutter's Way, John Heard is Cutter and Jeff Bridges is Bone.)

Oh man, there are no sweet dreams when the disillusionment of Vietnam comes home to America. In Newton Thornburg's Cutter and Bone (1976), Alex Cutter is a paranoid, scarred, and disabled Vietnam vet, and Richard Bone is a hedonistic dude, fond of drink and getting high, who abandons his family and advertising career to scrape by as a gigolo. (In the 1981 movie based on the book, Cutter's Way, John Heard is Cutter and Jeff Bridges is Bone.) One night when Bone is drunk, he thinks he sees a man dumping a bag of golf clubs into an alley trash can; however, the next day he realizes that what he saw was the disposal of a high school girl's dead body. Although it was dark, and Bone saw the distant man only in silhouette, when he sees a newspaper photo of Missouri corporate tycoon J. J. Wolfe, Bone exclaims, "It's him!" This electrifies Cutter, and, although Bone tries to backpedal, Cutter will have none of that. Cutter seeks justice for the girl, sure, but bringing revenge on Wolfe will somehow fix what happened to Cutter in Vietnam and what's wrong with the country he returned to. Bone allows himself to be overruled, and he and Cutter head to the Ozarks to investigate.

One night when Bone is drunk, he thinks he sees a man dumping a bag of golf clubs into an alley trash can; however, the next day he realizes that what he saw was the disposal of a high school girl's dead body. Although it was dark, and Bone saw the distant man only in silhouette, when he sees a newspaper photo of Missouri corporate tycoon J. J. Wolfe, Bone exclaims, "It's him!" This electrifies Cutter, and, although Bone tries to backpedal, Cutter will have none of that. Cutter seeks justice for the girl, sure, but bringing revenge on Wolfe will somehow fix what happened to Cutter in Vietnam and what's wrong with the country he returned to. Bone allows himself to be overruled, and he and Cutter head to the Ozarks to investigate.Cutter and Bone is haunting. It's not so much about redemption, as the conflict between alienated prodigal sons and corrupt authority figures. It takes place mostly in Santa Barbara, California, the same lushly beautiful beach town that provides an incongruous setting for Margaret Millar's novels about society's misfits. (It's also the model for Sue Grafton's fictional Santa Teresa, home of private eye Kinsey Millhone.) Thornburg's dialogue is pitch perfect, and you won't forget his two young men.

Noirish thrillers are perfect for night-time reading. But let's say your car needs a new muffler, your dog chewed one of your favorite shoes, or your spouse's spaghetti gave you indigestion. For whatever reason, you don't have the heart for noir, no matter how wonderful. Fix yourself a cup of tea and have one of these almond biscotti. What to read? Perhaps a little something before turning off the lights. Karen Russell's Vampires in the Lemon Grove, George Saunders's Tenth of December, and Jess Walter's We Live in Water are all enchanting 2013 short-story collections.

Maybe you want something more substantial than a short story. Outstanding British humor? Try the 1889 masterpiece by Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog), about the holiday boating trip on the Thames between Kingston and Oxford taken by friends Harris and George and their dog Montmorency. Others: Henry Howarth Bashford's Augustus Carp, Esq., by Himself: Being the Autobiography of a Really Good Man. The Diary of a Nobody (1892), which details 15 months in the life of Mr. Charles Pooter, was written by brothers George and Weedon Grossmith. Cold Comfort Farm (1932), by Stella Gibbons. Stephen Potter's The Theory and Practice of Gamesmanship (or the Art of Winning Games without Actually Cheating) (1947). Gerald Durrell's autobiographical My Family and Other Animals (1956).

Or, snuggle back into your pillow and roll your eyes at Dornford Yates's "Berry" Pleydell, his family, and close friends—British aristocrats who find themselves fish out of water, as England experiences social and financial upheaval between the World Wars. In the seventh series book, The House that Berry Built (1945), the Pleydells sell their ancestral pile in Hampshire, England, and flee to the cheaper South of France, where they believe aristocrats are still appreciated. There, Berry builds Gracedieu, a mountainside château, patterned after Cockade, the author's own French residence. The joy of this comic novel is in the very detailed description of Gracedieu's construction process. As World War II approaches, the Pleydells are forced to skedaddle once more.

Or, snuggle back into your pillow and roll your eyes at Dornford Yates's "Berry" Pleydell, his family, and close friends—British aristocrats who find themselves fish out of water, as England experiences social and financial upheaval between the World Wars. In the seventh series book, The House that Berry Built (1945), the Pleydells sell their ancestral pile in Hampshire, England, and flee to the cheaper South of France, where they believe aristocrats are still appreciated. There, Berry builds Gracedieu, a mountainside château, patterned after Cockade, the author's own French residence. The joy of this comic novel is in the very detailed description of Gracedieu's construction process. As World War II approaches, the Pleydells are forced to skedaddle once more. I could go on forever, talking about books for bed, because, really, what books aren't suitable there? It's eminently satisfying to lie flat on my back between the sheets, book raised above my face, and read about, say, corpses who can't lie still and must lurch around like zombies. Or corpses lying as quietly as I am. For example, Lee Child's Without Fail involves Jack Reacher's attempts to stop assassins targeting the new American vice president. In The Crossing Places, by Ellie Griffiths, forensic archaeologist Ruth Galloway is called when a child's bones are found on a Norfolk, England beach. Or people who might be rolled up in sheets to lie quietly. You may be familiar with Oregon psychiatric patient, Randle McMurphy, in Ken Kesey's 1962 classic, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (made into a movie that won the Academy Award for Best Picture); and hospital patients in Dennis Lehane's Shutter Island (2003) (Martin Scorcese directed the movie). But have you met the man who wakes up with no memories in a mental institution and pulls himself back together in Virginia Perdue's excellent suspense Alarum and Excursion (1944)?

I could go on forever, talking about books for bed, because, really, what books aren't suitable there? It's eminently satisfying to lie flat on my back between the sheets, book raised above my face, and read about, say, corpses who can't lie still and must lurch around like zombies. Or corpses lying as quietly as I am. For example, Lee Child's Without Fail involves Jack Reacher's attempts to stop assassins targeting the new American vice president. In The Crossing Places, by Ellie Griffiths, forensic archaeologist Ruth Galloway is called when a child's bones are found on a Norfolk, England beach. Or people who might be rolled up in sheets to lie quietly. You may be familiar with Oregon psychiatric patient, Randle McMurphy, in Ken Kesey's 1962 classic, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (made into a movie that won the Academy Award for Best Picture); and hospital patients in Dennis Lehane's Shutter Island (2003) (Martin Scorcese directed the movie). But have you met the man who wakes up with no memories in a mental institution and pulls himself back together in Virginia Perdue's excellent suspense Alarum and Excursion (1944)? More sheets find their way onto mummies; for example, in books by Elizabeth Peters, featuring feminist Amelia Peabody, a Victorian Egyptologist. In Dermot Morrah's 1933 charmer, The Mummy Case Mystery, the police are satisfied that the charred body in Oxford Professor Benchley's room is the professor and not the newly acquired mummy of Pepy I. Professors Sargent and Considine aren't so sure. There should be two bodies, not one. Their investigation is full of Oxford ambience, wit, and red herrings.

More sheets find their way onto mummies; for example, in books by Elizabeth Peters, featuring feminist Amelia Peabody, a Victorian Egyptologist. In Dermot Morrah's 1933 charmer, The Mummy Case Mystery, the police are satisfied that the charred body in Oxford Professor Benchley's room is the professor and not the newly acquired mummy of Pepy I. Professors Sargent and Considine aren't so sure. There should be two bodies, not one. Their investigation is full of Oxford ambience, wit, and red herrings.Now, I'm getting sleepy. I'll have to finish Gerald Seymour's fine book of espionage, 2000's A Line in the Sand, tomorrow night. I love reading in bed. If you haven't already, I strongly suggest you give it a try.