Where Monsters Dwell by Jørgen Brekke

Where Monsters Dwell by Jørgen BrekkePresent-day seers without the benefit of oracles from Delphi have confidently predicted what the future holds for the "14ers" (babies born in 2014). Apparently, along with car keys, DVDs and light bulbs that work, dead tree books are something those little hands will never hold. I will boldly take the position that the Golden Books and Dr.Seuss are safe for a while, because tiny fingers can access them easily (no password protection) and they taste better too. It’s amazing to contemplate the disappearance of something that has been highly valued for centuries.

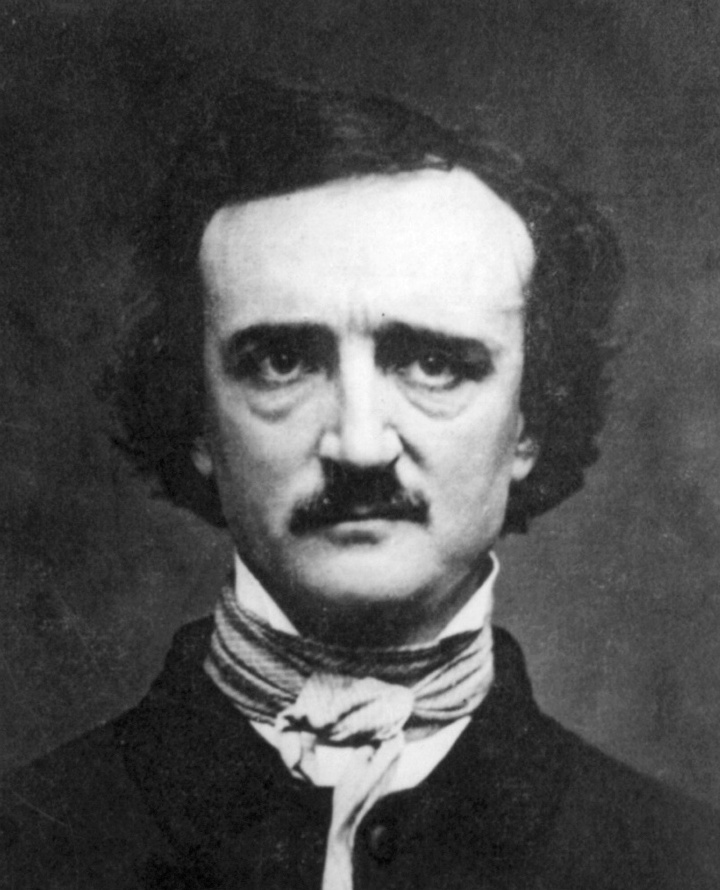

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore." ("The Raven," Edgar Allan Poe)

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore." ("The Raven," Edgar Allan Poe)Of course, that is because the value of a book extends far beyond the words encompassed between its covers. Sometimes, a good story can encapsulate some of the essence of the value of writing, and writers and books that have crossed the paths of many individuals and affected their lives by their very existence.

This is the case in Jørgen Brekke’s Where Monsters Dwell (translated from the Norwegian by Steven T. Murray; to be published by Minotaur on February 11, 2014).

It all starts with a book, a

unique volume, the only one of its kind.

It all starts with a book, a

unique volume, the only one of its kind.Efrahim Bond was working as a librarian in his office at the Edgar Allan Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia. He had ended up there after a somewhat nomadic career, but was satisfied because he had come across the find of a lifetime. He had fragments of a book known as The Johannes Book, written by a mendicant friar who lived in Norway during the 1500s.

It was a book handwritten on parchment, from an age when paper was becoming more common. From what Bond could read, the book contained confessions of a grisly nature. He heard a knock.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, / Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore— / While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, / As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door." / 'Tis some visiter," I muttered, "tapping at my chamber door— / Only this and nothing more." ("The Raven," Edgar Allan Poe)

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, / Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore— / While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, / As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door." / 'Tis some visiter," I muttered, "tapping at my chamber door— / Only this and nothing more." ("The Raven," Edgar Allan Poe) It was the

cleaning woman at the museum who made the gruesome

discovery of Efrahim Bond's remains, in a state worse than anything imagined by the

master of the macabre himself, Edgar Allan Poe. Poe spent much of his childhood in Richmond, Virginia, and studied at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville before he enlisted in the military. While in Richmond, he enjoyed the full use of his mental faculties; it was only later that he began to have periods of mental problems that remain undefined to this day.

It was the

cleaning woman at the museum who made the gruesome

discovery of Efrahim Bond's remains, in a state worse than anything imagined by the

master of the macabre himself, Edgar Allan Poe. Poe spent much of his childhood in Richmond, Virginia, and studied at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville before he enlisted in the military. While in Richmond, he enjoyed the full use of his mental faculties; it was only later that he began to have periods of mental problems that remain undefined to this day. About

the same time Efrahim was meeting his fate, in a Kingdom by the Sea (a/k/a Norway, by the Norwegian, the North

and Barents Seas) Jon Vatten rode his disintegrating bicycle to the Gunnerus

Library in Trondheim, Norway, where he worked as the chief of security. One of the main treasures of this library is The Johannes Book.

About

the same time Efrahim was meeting his fate, in a Kingdom by the Sea (a/k/a Norway, by the Norwegian, the North

and Barents Seas) Jon Vatten rode his disintegrating bicycle to the Gunnerus

Library in Trondheim, Norway, where he worked as the chief of security. One of the main treasures of this library is The Johannes Book. Those who dream by day are cognizant of many things

which escape those who dream only by night. ("Eleonora," Edgar Allan Poe)

Those who dream by day are cognizant of many things

which escape those who dream only by night. ("Eleonora," Edgar Allan Poe)Vatten liked weekends best, because he had free time to work a bit on his thoughts about what actually killed Edgar Allan Poe. He was fascinated by the idea that such a preeminent writer should die destitute. He’d had the opportunity to visit the museum in Richmond, Virginia, the summer before.

"Every

poem should remind the reader that they are going to die." (Edgar Allan Poe)

"Every

poem should remind the reader that they are going to die." (Edgar Allan Poe)Before Vatten got settled into his day, he was introduced to a new librarian named Siri Holm. Her avocation was to figure out the identity of the villain in any murder mystery before the end of the first third of the book. To do this, she has some interesting theories. But, perhaps, her main skill was seduction. The Gunnerus Library passed a quiet weekend, but on Monday morning a mutilated body was found in the book vault by the head of the library.

Now this is the point. You fancy me mad. Madmen know nothing. But you should have seen me. You should have seen how wisely I proceeded.... ("The Tell-Tale Heart," Edgar Allan Poe)

The body is that of the librarian Gunna Britte Dahle, whom Siri had just replaced. Gunna had also been to the Poe museum in Richmond in recent months. The motive for the killing was unclear but it, like the murder in Richmond, had the air of fiction about it, as if it had been imagined ahead of time.

Over the Mountains / Of the Moon, / Down the Valley of the Shadow, / Ride, boldly ride ("Eldorado," Edgar Allan Poe)

Over the Mountains / Of the Moon, / Down the Valley of the Shadow, / Ride, boldly ride ("Eldorado," Edgar Allan Poe)Felicia Stone of the Richmond police follows her nose and some subtle clues, which lead her to the Norway connection, and she works with Chief Insp. Odd Singsaker of the Trondheim police to make sense of the madness. The murderer is not yet finished and the clues are few.

Grains of the golden sand— / How few! yet how they creep / Through my fingers to the deep, / While I weep—while I weep! ("A Dream within a Dream," Edgar Allan Poe)

Despite the fact that I found the murders extremely grisly, the story itself was intriguing.

Jørgen Brekke interweaves a marvelous

history of the creation of The Johannes Book into the story, and tells the

reader a fascinating tale of how anatomic dissection first became acceptable as

a route to medical knowledge, then finally legal. He also gives some absorbing

details of how early books were put together in the era when the basic raw

materials were scarce. Imagine the excitement when, over 500 years ago, printer Teobaldo Manucci (a/k/a Aldus Manutius) invented strange

little vellum-bound books that a reader could easily carry under his arm. Brekke's scattered pearls of the life history of Edgar Allan Poe were decorations on the cake.

Jørgen Brekke interweaves a marvelous

history of the creation of The Johannes Book into the story, and tells the

reader a fascinating tale of how anatomic dissection first became acceptable as

a route to medical knowledge, then finally legal. He also gives some absorbing

details of how early books were put together in the era when the basic raw

materials were scarce. Imagine the excitement when, over 500 years ago, printer Teobaldo Manucci (a/k/a Aldus Manutius) invented strange

little vellum-bound books that a reader could easily carry under his arm. Brekke's scattered pearls of the life history of Edgar Allan Poe were decorations on the cake.We gave the Future to the winds, and slumbered tranquilly in the Present, weaving the dull world around us into dreams. ("The Mystery of Marie Rogêt," Edgar Allan Poe)

The pundits may be correct in their predictions of a society without dead-tree books. In my own office, magazines are disappearing since the advent of e-readers, the Kindle app and newspaper apps for smart phones. But most of the people I ask have no idea of the name of the book they are reading, nor its author––and it doesn’t seem to matter to them, because the books themselves are simply chosen because they are free or very low cost.

A niece of mine goes to a school where there are no textbooks, only iPads, and the students get along very well. I will have to check whether crayons have gone the way of cursive in this school. Surely Crayola crayons are here to stay.

A niece of mine goes to a school where there are no textbooks, only iPads, and the students get along very well. I will have to check whether crayons have gone the way of cursive in this school. Surely Crayola crayons are here to stay.In fact, the country’s first totally digital public library system opened in San Antonio, Texas this week. The place (can it really be called a library?) is called Bibliotech. Appropriately, this name is inspired in part from the Spanish word for library––biblioteca. The Oxford English Dictionary defines library as "a building or room containing collections of books, periodicals, and sometimes films and recorded music for people to read, borrow, or refer to." So it is an appropriate use of the word.

There were patrons lining up to check out the online catalog on Apple touchscreen computers and check out books on e-readers. Say goodbye to judging a book by its cover.

There have been other libraries without printed books; for one, the Tucson-Pima Public library system opened such a branch, but the people who lived in the community demanded print books be added to the shelves. I am not alone.

Note: I received a free review copy of Brekke's Where Monsters Dwell. Some versions of this review may appear elsewhere under my user name there.