Today, we'll wrap up our discussion of the year-end lists of our favorite reads in 2014.

Today, we'll wrap up our discussion of the year-end lists of our favorite reads in 2014. Georgette Spelvin: I'm not the person Sister Mary Murderous should ask for help in kicking her book-buying habit. She lays waste to my own pocketbook with her emails that begin, "I just

ran across a book with your name all over it, Georgette." I've been afraid to ask her exactly what this means, but she definitely has my number. In addition to directing me to Marlon James's A Brief History of Seven Killings last year, she suggested several of my favorite reads from the year before: Philipp Meyer's The Son, an epic about the McCullough family of Texas, from the pre-Civil War days to post-9/11; and The Infatuations by Javier Marías, a novel that uses a supposedly random homicide to examine guilt,

mortality, and truth. And we both loved Kate Atkinson's Life After Life, Nick Harkaway's Angelmaker, and Graeme Simsion's The Rosie Project in 2013 (see here).

Georgette Spelvin: I'm not the person Sister Mary Murderous should ask for help in kicking her book-buying habit. She lays waste to my own pocketbook with her emails that begin, "I just

ran across a book with your name all over it, Georgette." I've been afraid to ask her exactly what this means, but she definitely has my number. In addition to directing me to Marlon James's A Brief History of Seven Killings last year, she suggested several of my favorite reads from the year before: Philipp Meyer's The Son, an epic about the McCullough family of Texas, from the pre-Civil War days to post-9/11; and The Infatuations by Javier Marías, a novel that uses a supposedly random homicide to examine guilt,

mortality, and truth. And we both loved Kate Atkinson's Life After Life, Nick Harkaway's Angelmaker, and Graeme Simsion's The Rosie Project in 2013 (see here).All of the books on Sister Mary's 2014 list have migrated onto my library request list. The two that have me tapping an impatient foot in anticipation are her absolute favorite, Ben Macintyre's A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal (The Brits! Cambridge! Spies!) and Phil Hogan's A Pleasure and a Calling. Hogan's William Heming, a British real estate agent who takes advantage of home buyers who don't bother to change the locks after they purchase a house from him, brings to mind Canadian writer Russell Wangersky’s Walt (Spiderline, 2014), a grocery store janitor who collects shopping lists customers leave behind. Walt's wife has disappeared and so have some of the store's female customers. I think winter nights scream out for hair-raising psychological suspense and sinister protagonists. Don't you?

Another of Della's picks, Station Eleven, by Emily St. John, is an original take on a post-apocalyptic America, and I enjoyed it. I haven't read James L. Cambias's A Darkling Sea, with Earthlings, lobster-like Ilmatarans, and six-legged Sholen at loggerheads on a planet far from Earth, but it sounds like a lot of fun.

I'm always anxious to meet fellow literature lovers, even if they're fictional characters like Aalyia Sohbi of Beirut in Rabih Alameddine's An Unnecessary Woman.

|

| Sir Ian McKellen in Mr. Holmes |

|

| Hugh Laurie as Bertie Wooster and Stephen Fry as Jeeves |

Okay, let's straighten up in our chairs and think about books that are more serious before we look at some satire. In Malcolm Lowry's masterpiece, Under the Volcano, Geoffrey Firmin's most important relationship isn't with his wife, Yvonne––it's with alcohol. On the Day of the Dead in 1938, he resigns his post as British Consul, sits at a bar, and resolves to drink himself to death. It's a powerful read about guilt and the struggle for redemption. I'd like to read Alice McDermott's Charming Billy, featuring another alcoholic.

I enjoyed Nigel Williams's satirical The Wimbledon Poisoner (see review here), in which a man likes the image of himself as a grieving widower so much he sets out to murder his wife. Unfortunately, his skill set doesn't include pinpoint killing, and his neighbors pay the price for his bumbling. After seeing this other Williams book, Unfaithfully Yours, on Lady Jane Digby's Ghost's list and reading Sister Mary's comments, I scurried to the Book Depository website to order it.

LJDG's comments about Lissa Evans's Crooked Heart are too much for me to resist: "A small part of the reader's heart will be left with the suffragette medal given new love in Noel's charitable hands. This is a wonderful, unforgettable read." (Regarding India Knight's blurb about the book: Sister Mary isn't the only one who loves Nancy Mitford's The Pursuit of Love. You really should read that book and also Dodie Smith's witty and moving coming-of-age novel, I Capture the Castle. It has one of literature's best first lines: "I write this sitting in the kitchen sink.")

|

| Not only eggs are hardboiled |

If you haven't read any of Block's hardboiled Scudder books, I'll suggest a couple you could start with: Eight Million Ways to Die (a prostitute finds big trouble when she wants to quit her profession) or When the Sacred Ginmill Closes (Scudder looks back to the 1970s when he was drinking heavily and juggling several investigations for friends). Or, if you want to start at the beginning, that's The Sins of the Fathers, in which the father of a dead prostitute asks Scudder to investigate.

Della Streetwise: Around Thanksgiving, I resolved to increase my reading speed in 2015. I have now made a startling discovery that will have me reading at warp speed by year's end. As my reading velocity has increased, so has my rate of new book acquisition. Because these two activities are positively correlated, my reading pace should therefore increase if I merely step up my purchases and library requests. I can utilize these Read Me Deadly year-end lists guilt-free because they're helping me keep my New Year's resolution!

Della Streetwise: Around Thanksgiving, I resolved to increase my reading speed in 2015. I have now made a startling discovery that will have me reading at warp speed by year's end. As my reading velocity has increased, so has my rate of new book acquisition. Because these two activities are positively correlated, my reading pace should therefore increase if I merely step up my purchases and library requests. I can utilize these Read Me Deadly year-end lists guilt-free because they're helping me keep my New Year's resolution! |

| What is this other than a bird's eye view? |

I haven't read a Camilleri mystery for quite some time and am glad to be reminded of his cynical Sicilian police inspector, Salvo Montalbano. Montalbano knows how to live by balancing work with pleasure. I'm going to bring some Italian warmth into my living room this winter with Camilleri's Treasure Hunt and MC's other Italian suggestion, Maurizio de Giovanni's I Will Have Vengeance.

I'm coming to rely on Lady Jane Digby's Ghost for recommendations of British authors (onto my list goes Unfaithfully Yours by Nigel Williams) and unforgettable characters (Crooked Heart by Lissa Evans). Like Sister MM, I rushed to get Ben Elton's Time and Time Again after hearing about it from LJDG. Hugh Stanton takes the responsibility for staving off the shot that signaled the first World War. It's a fascinating book and I'm still thinking about what it means. It reminded me of another book, Rebecca Makkai's The Hundred-Year House (Viking, 2014). In that book, actions and possessions of Laurelfield residents are repeatedly overlooked or misinterpreted during later decades. The unintended consequences of these mistakes stack up over a hundred years and remind us that we can't look into a crystal ball and see clearly when we can't even interpret history perfectly.

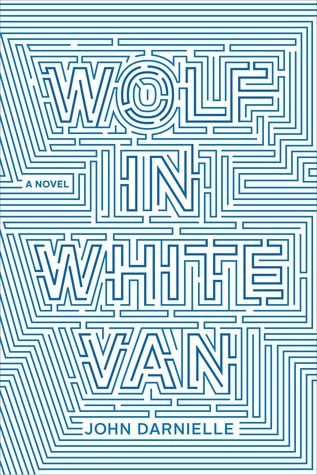

LJDG tells us the extremely careful Robert Purcell causes an accidental death and disrupts the perfection of his carefully planned life in Jon Canter's A Short Gentleman. Of course, I'm going to have to read this along with Georgette's recommendation for books about the consequences of choices, Wolf in White Van, by John Darnielle.

Michel Faber's sci fi, The Book of Strange New Things, looks like a must read. I'm interested in how people balance pressures exerted by their own needs against their loved ones' and society's. I'd like to see what happens when Peter Leigh, a human minister on another planet, is caught between his employer, his congregation of extraterrestrials and his wife on a disintegrating Earth.

I still haven't gotten around to reading the book that mopped up all 2014 sci fi awards, Ann Leckie's Ancillary Justice (Orbit, 2013). Its heroine was once one of a thousand mindless humans controlled by a spaceship's artificial intelligence but she is now her ship's only remaining consciousness. I've also ordered Dave Hutchinson’s Europe in Autumn (Solaris, 2014), "a thriller of espionage and the future which reads like the love child of John le Carré and Franz Kafka." This book is set in a Europe fractured into many little pieces by economic disaster and a flu pandemic. I still have room on my shelves for sci-fi Georgette liked: Cixin Liu's The Three-Body Problem, which sounds mind-blowing, and Andy Weir's The Martian, also given a thumbs up by Sister MM's husband and Becky LeJeune.

Of course, we're sorry to learn Sister MM is in any kind of distress. Notwithstanding the benefits we all receive from her books researching, reading and reporting, we're more than happy to respond to her request for help with a books addiction. Might I suggest she go to bed an hour later so she can squeeze in more reading and feel better about the number of unread books on her shelf? Perhaps her husband could read to her at breakfast. There's also lunch and dinner.

Of course, we're sorry to learn Sister MM is in any kind of distress. Notwithstanding the benefits we all receive from her books researching, reading and reporting, we're more than happy to respond to her request for help with a books addiction. Might I suggest she go to bed an hour later so she can squeeze in more reading and feel better about the number of unread books on her shelf? Perhaps her husband could read to her at breakfast. There's also lunch and dinner. While she's contemplating these ideas, I'll thank her for several books on her list that I already read at her suggestion, Robert Harris's Ian Fleming Steel Dagger winner, An Officer and a Spy, and Terms & Conditions by Robert Glancy. I have Christopher Fowler's Bryant & May and the Bleeding Heart in the pipeline. That weird William Heming, who keeps the keys to houses he sells, gives me the shivers so I must read A Pleasure and a Calling by Phil Hogan.

I'm pondering my next read (quickly) as I bid you goodbye. I hope everyone is off to a good start reading in 2015.