Here we are again, previewing books. It's a fun time for us Material Witnesses because as we're spotting promising books for ourselves, we're also assessing books for each other. There's a World War II book for Sister Mary. Noir? Georgette. I bet Peri would like that one by Karin Fossum. And that European police procedural? It has the Maltese Condor's name all over it. Among the five of us, I hope we're showing you some books that are up your alley, too.

Recently, I've been watching the TV series

The Americans. It's set in the 1980s and concerns two Soviet KGB officers. They're posing as a married couple, Elizabeth and Philip Jennings, living in suburban Washington, DC with their kids. More than a story about spies,

The Americans is the story of these two Russians and their marriage. (Sister Mary wrote about the first season of the series

here.)

Chinese-American novelist Ha Jin (pen name of Xuefei Jin) uses an espionage novel,

A Map of Betrayal (Pantheon, November 4), in a similar way. He examines Gary Shang's divided loyalties in both love and politics. Shang loves China, where he was born and married. He also loves the United States, where he has an American wife, a daughter, Lilian, a trusted Chinese-American mistress––and a job as a Chinese mole at the CIA.

The book is narrated by the adult Lilian, who received her father's diaries from his mistress after her parents' deaths. Lilian knows the US convicted her father of treason, but she knows nothing of his previous existence in China.

A Map of Betrayal follows two story lines written from two different perspectives: Gary Shang's life, as he lived it, and Lilian's attempts to learn about it after his death. Ha Jin is a masterful writer about conflicted individuals (in

Waiting, for example, a man waits 18 years to divorce his wife because he loves another and, once divorced, isn't happy about it). This one sounds both complex and moving.

Many of us love books set in the world of books, in which the characters are librarians, writers, publishers, booksellers or obsessional readers. Here's one like that.

The Forgers will be published by Mysterious Press on November 4th. Its author, Bradford Morrow, is known for his gothic tales about troubled (and troubling) people. From the beginning, we're unsure how much we can trust the narrator, Will. He tells us he was a gifted forger of 19th-century manuscripts and signatures, but that life was behind him when Adam Diehl is found, dead and his hands severed, surrounded by his collection of rare manuscripts and books.

Will's efforts to create a new life with Adam's sister, Meghan, are hampered when he receives threatening letters apparently written by authors from the grave. I doubt

The Forgers is as wonderfully bizarre as Marcel Theroux's

Strange Bodies (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, February 2014), in which letters penned by English literary figure Dr. Samuel Johnson are found on modern paper in 21st-century London. Still, it looks good to me.

No one familiar with Ruth Rendell's writing will look at the cover of her upcoming stand-alone,

The Girl Next Door (Scribner, October 7), and expect something lovely in that battered tin. No matter if she's writing about Chief Inspector Reginald Wexford, stand-alones or dark psychological suspense pseudonymously as Barbara Vine, Rendell sees evil simmering under the surface of everyday suburbia.

Construction work unearthed the tin box containing a pair of mismatched hands on Essex property where children played in underground tunnels during World War II. After a police inspector tracks them down, the now-elderly friends get together to investigate their childhood secrets. Among the amateur investigators are Alan and his wife, Rosemary; widowed Daphne, whom Alan once loved; Michael, whose mother disappeared and who now considers getting together with his distant father; and Lewis, whose Uncle James was occasionally in the tunnels before he too disappeared. While thinking about this novel, I pictured the final scene of the movie

Deliverance, in which Ed awakens screaming from a nightmare when a dead hand reaches above the surface of a lake. A recurring theme in mystery fiction is the decades-old crime solved when it reaches into the present. There's something artistically pleasing about it reaching with a long-dead hand. Or two.

Let's set aside the morality of a career murdering people and think about it in purely practical terms. The job stress would drive me totally bonkers and I'm curious about people who become pro killers and what they do if they live long enough to retire (see

Who Ya Gonna Call? here). Don Winslow's Frank Machianno surfs and sells fish in San Diego now that he's no longer Frankie Machine, the Mafia's efficient killer (

The Winter of Frankie Machine). In Lenny Kleinfeld's hip and hilarious

Shooters & Chasers, a crew of killers is headed by Arthur Reid, a wine connoisseur whose retirement goal is owning a vineyard that supplies a great red for a White House state dinner.

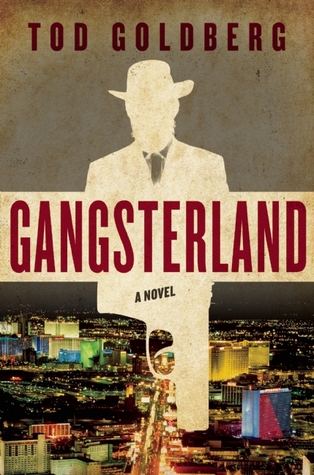

Tod Goldberg's

Gangsterland (Counterpoint, September 9) features a Chicago Outfit killer, Sal Cupertino, who might feel at home with Kleinfeld's eccentric characters. Sal longs to be reunited with his wife and toddler and simply disappear. But he messed up and killed three FBI agents and the feds are now on his trail. After Sal undergoes several plastic surgeries and does a lot of studying, the crime syndicate resurrects him in Las Vegas, where they expect his help in an organized crime scheme operating out of a local synagogue, of all places. Yes, Sal is now Rabbi David Cohen, who delivers rabbinical homilies sprinkled with lyrics from Springsteen. Goldberg's book is earning reviewers' praise, including this verdict from

Kirkus: "Clever plotting, a colorful cast of characters and priceless situations make this comedic crime novel an instant classic."

Ha Jin isn't the only writer on my fall books-to-read list to explore the topics of love and betrayal. David Bezmozgis wrote his book,

The Betrayers (Little, Brown, September 23), before Gaza erupted this summer, but his themes of patriotism, sacrifice, ultimate truth, what it means to be a moral man and the double-edged nature of deeply-held principles are timeless.

The book is set over the course of a day in August 2013. A smear campaign targeting Israeli politician Baruch Kotler, who supports West Bank settlements, causes the married Kotler and his much-younger mistress, Leora, to flee to a Crimean resort town Kotler remembers from his childhood. A surprise for Kotler awaits at the house the couple has rented. The owner is Chaim Tankilevich, the friend who betrayed Kotler to the KGB four decades earlier. Kotler was sentenced to 13 years in a gulag. Both men have suffered in the past, and both struggle with issues now. In a settling of scores, who owes what to whom?

I'm thinking about recent events in Ferguson, Missouri, and what they say about race relations in the US as I add Walter Mosley's

Rose Gold (Doubleday, September 23) to my list of fall books. It's 13th in the series about Easy Rawlins, a World War II vet who moved from Texas to Los Angeles in the late 1940s. Easy opened a "research and delivery" office because, as a black man, he was unable to obtain a private detective's license. Over the years, white city leaders have consulted him when they need a bridge to the black community. In exchange, Easy received a PI license, but there is still only one white cop Easy trusts.

Mosley is a gifted storyteller, and Easy is about as engaging a narrator as you could possibly meet. Through his observations and experiences, he delivers a picture of what life is like for a street-smart but honorable and hard-working black man in Los Angeles from the late '40s to 1967. That's the year he purposefully runs his car off the road (

Blonde Faith, 2007). Several months later, he's out of a coma and searching for a missing young man among hippies on Sunset Strip (

Little Green, 2013; see review

here). In

Rose Gold, it's still 1967. Easy juggles several cases at once, including one for Roger Frisk, assistant to the chief of police. Frisk asks Easy to find Rosemary Goldsmith, daughter of a weapons manufacturer. She has disappeared from her UC Santa Barbara dorm and there's a question of whether a black ex-boxer, who changed his name to Uhuru Nolica and leads the revolutionary group Scorched Earth, is involved. The feds and other LA cops try to warn off Easy but good luck with that. As usual, Easy will trade favors and use his head to clear things up. Having Easy for company in a case with shades of Patty Hearst spells an irresistible read.

I'm fascinated by people (and fictional characters) who refuse to be shackled by society's expectations. I recently enjoyed Erin Lindsay McCabe's

I Shall Be Near to You (Crown, January 2014) about one such woman. When her husband, Jeremiah Wakefield, joins the Union Army, Rosetta Edwards won't hear of staying home. She becomes "Ross Stone" and fights in the American Civil War at his side with other volunteers from rural New York who keep her secret. This book is based on letters home by women who actually fought in the Civil War.

Rosetta Edwards doesn't want her husband to enlist, and

I Shall Be Near to You is primarily a love story. In contrast, in Laird Hunt's

Neverhome (Little, Brown, September 9), narrator Constance Thompson feels so strongly about supporting the Union cause she enlists as "Ash" Thompson while her husband, Bartholomew, stays home on their Indiana farm. She's a crack shot and fits in with the men until she's betrayed by someone she thought she could trust. Reviewers' raves compare

Neverhome to Charles Frazier's

Cold Mountain, but describe Constance's journey as her own.

Publishers Weekly says, "Hunt’s characterization of Constance transcends simplistic distinctions between male and female, good and bad. The language of her narration is triumphant as well: sometimes blunt, sometimes visionary, and always fascinating."

I'll give you a few of the steps I went through to research Robert Jackson Bennett's book,

City of Stairs (Broadway Books/Random House paperback original, September 9), about intelligence officer Shara Komayd's investigation of the politically explosive murder of academic Efrem Pangyui in the city of Bulikov.

I read the publisher's blurb ("A densely atmospheric and intrigue-filled fantasy novel of living spies, dead gods, buried histories, and a mysterious, ever-changing city—from one of America’s most acclaimed young SF writers"), Georgette's

post about a previous Robert Jackson Bennett book,

American Elsewhere, and a starred

Library Journal review of

City of Stairs. It states, in part, "The world Bennett (The Troupe; American Elsewhere) has constructed is a complex political landscape of a subjugated people holding onto the memories of their glory days and protective gods and the conquerors reaping revenge for their own previous subjugation. An excellent spy story wrapped in a vivid imaginary world." This book is definitely for me. Is it also for you?

Next week, I'll tell you about more fall books I'm excited about. Tomorrow, we'll see some other books that caught Georgette's eye.

Recent reading has me contemplating human nature and destiny. Before we get to the actual books that inspired this thinking, we could warm up our minds by looking at Shakespeare for Cassius's ideas about being our own masters versus the fault in our stars or King Henry IV's desire to peek at the book of fate; however, it's Monday, and our heads are already spinning without the stimulus of the Bard. Let's ask instead why the chicken crossed the road. And no, we can't say it's simply to get to the other side.

Recent reading has me contemplating human nature and destiny. Before we get to the actual books that inspired this thinking, we could warm up our minds by looking at Shakespeare for Cassius's ideas about being our own masters versus the fault in our stars or King Henry IV's desire to peek at the book of fate; however, it's Monday, and our heads are already spinning without the stimulus of the Bard. Let's ask instead why the chicken crossed the road. And no, we can't say it's simply to get to the other side.

That sort of thing doesn't just slip unnoticed into the night. Jeff is placed on administrative leave. In the meantime, the Mob hustles Sal out of town for a series of plastic surgeries and quiet time for studying the Talmud (not difficult for Sal, who is known as "the Rain Man" for his memory), and then resurrects him as Rabbi David Cohen in Las Vegas. Las Vegas isn't what it used to be for organized crime, what with the corporatization of gambling and casinos, but there are still ways for connected guys to muscle in on the action in secondary markets, including construction, strip clubs, and drugs not handled by the Bloods and Crips. Believe it or not, there's even a place for a man like Sal at Temple Beth Israel, whose growing complex houses two rabbis, a mortuary, a cemetery, and a private school.

That sort of thing doesn't just slip unnoticed into the night. Jeff is placed on administrative leave. In the meantime, the Mob hustles Sal out of town for a series of plastic surgeries and quiet time for studying the Talmud (not difficult for Sal, who is known as "the Rain Man" for his memory), and then resurrects him as Rabbi David Cohen in Las Vegas. Las Vegas isn't what it used to be for organized crime, what with the corporatization of gambling and casinos, but there are still ways for connected guys to muscle in on the action in secondary markets, including construction, strip clubs, and drugs not handled by the Bloods and Crips. Believe it or not, there's even a place for a man like Sal at Temple Beth Israel, whose growing complex houses two rabbis, a mortuary, a cemetery, and a private school.

As we know from Homer's Iliad, the Trojan War was prompted by Aphrodite's promise that Trojan prince Paris could have the world's most beautiful woman. Thus, Paris abducted––or eloped with––Queen Helen of Sparta. Her husband's brother, King Agamemnon of Mycenae, led forces gathered from around the Hellenic world to lay siege to Troy and get her back. While the Greeks are waiting, Agamemnon orders Achilles to pillage some nearby cities for treasure and women captives. While sacking Lyrnessos, Achilles meets Briseis, a beautiful young healing priestess and wife of Prince Mynes, when she tries to kill him. Of course, they fall in love.

As we know from Homer's Iliad, the Trojan War was prompted by Aphrodite's promise that Trojan prince Paris could have the world's most beautiful woman. Thus, Paris abducted––or eloped with––Queen Helen of Sparta. Her husband's brother, King Agamemnon of Mycenae, led forces gathered from around the Hellenic world to lay siege to Troy and get her back. While the Greeks are waiting, Agamemnon orders Achilles to pillage some nearby cities for treasure and women captives. While sacking Lyrnessos, Achilles meets Briseis, a beautiful young healing priestess and wife of Prince Mynes, when she tries to kill him. Of course, they fall in love.