Here are Georgette Spelvin and Della Streetwise with more summer reading suggestions. You didn't think we were finished stuffing your beach bags and stacking books by your patio chair on Friday, did you?

In hot weather, a brain can get cranky and finicky. A good reading choice will either soothe a crabby psyche or say yah boo sucks to this nonsense and jump-start a heat-exhausted mind with something unusually thought-provoking or exciting. The latter choice is akin to eating very spicy food when you're already sweating.

Combining these approaches works well when you're stuck inside a sweltering house, and there's no air conditioning. Stand in front of an open refrigerator while holding an action thriller or police procedural in one hand; grasp and quickly fan the fridge door with your other hand.

Alternatively, cool yourself by stepping into the bone-rattling cold of a western Ukrainian winter with Dan Smith's taut, disturbing thriller,

The Child Thief, published on June 1 by Pegasus Crime. It's sorta what you'd get if you popped David Benioff's

City of Thieves, Geoffrey Household's

Rogue Male, Tom Rob Smith's

Child 44, and the Brothers Grimm into the blender and served it all over ice.

It's December 1930 when the book begins, and Stalin's authorities, accompanied by soldiers, are fanning across Ukraine. The villagers of Vyriv are very afraid. That's why the sight of a staggering stranger, hauling a sled, menaces hunters Luka Mikhailovich Sidorov and his 17-year-old twin sons, Viktor and Petro.

Despite his sons' misgivings, Luka, our narrator, insists they carry the near-dead stranger back to Vyriv. Once there, the sled's mysterious and horrifying cargo upsets the already nervous villagers. In the ensuing melee, Luka's young niece Dariya disappears. Promising his daughter he'll bring Dariya back, Luka sets out the next morning with Viktor, Petro, and Dariya's father, following man-sized tracks in the snow. As the men brave deadly cold, they hunt the child thief ahead of them and worry about the village awaiting discovery behind them. This worry remains when the tables are turned, the hunted becomes the hunter, and they run into Stalin's men. You cannot help but root for Luka, his loyal sons, and comrades. Their humanity is inextinguishable, even in the cruel icebox of Stalin's Ukraine.

This book contains brutality against adults and some gruesome elements involving children. Despite these issues, I'm glad I read it. Smith has crafted a beautifully poetic and hugely tense thriller, populated by unforgettable characters, in

The Child Thief.

After leaving the unrelenting Ukrainian winter, I was ready for another book, albeit something much lighter. I gulped when I read the Robert Louis Stevenson quotation in the preface: "Everybody, soon or late, sits down to a banquet of consequences." But 20 pages in, I was saying aloud, "Thanks, Hank, I needed this." Hank is Hank Phillippi Ryan, and her multiple-award-winning career in investigative reporting and experience with political campaigns are put to use in

The Other Woman, published in 2012 by Tor. It's coming out in paperback tomorrow, July 2nd, perfect timing for tucking into a beach or airline carry-on bag.

It's one of those books that lets you relax while the point of view shifts from one character to the next, and you only gradually see where everyone fits into the plot. Ryan skillfully ties together a political campaign, a series of deaths, and personal betrayals through the investigations of her two main characters, investigative reporter Jane Ryland and Boston PD Detective Jake Brogan.

The sweetness of Jake and Jane's near-romance, the All-hands-on-deck! approach to the political and personal shenanigans, and writer Ryan's spin-the-bottle pointers to an "other woman" made me smile as I sat in the shade, sipping a vodka collins. This is the first in a new series, with the next,

The Wrong Girl, due on September 10th.

A quick note before we move to books I hope to read. I loved

Ghostman, Roger Hobbs's incredibly original and gritty debut (Knopf, February 2013), featuring fixer Jack Delton, who has 48 hours in which to clean up a botched Atlantic City casino heist. I'll tell you more about this book soon.

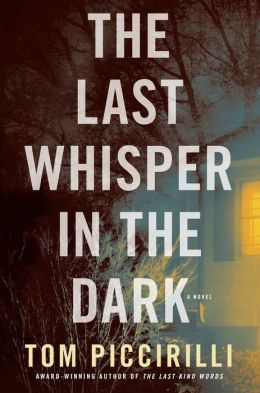

I like Tom Piccirilli's noir, in which he contrasts and compares ideas about right and wrong, honor, and redemption in law -breaking and -abiding folks. (Don't you love the incongruity of a professional killer in

Pulp Fiction, who insists that a colleague say "please" and complains about someone who has purposefully scratched his car?)

Last year, I read Piccirilli's series first,

The Last Kind Words (discussed

here). It introduces a memorable clan of grifters, the Rands, whose traditions include stealing and giving their children names of dog breeds. Until the events described in this book, they had prided themselves on never crossing a line to commit crimes of violence. In the second of the series,

The Last Whisper in the Dark (Bantam, due July 9), Collie Rand is dead, and his brother Terrier ("Terry"), is deeply unhappy and attempting to go straight.

A couple of debut novels involving life after death are intriguing me:

The first is Ofir Touché Gafla's debut,

The World of the End, translated from the Hebrew by Mitch Ginsburg, and published last week by Tor.

Publishers Weekly calls it "part romance, part mystery, and part science fantasy." Its protagonist is Ben Mendelssohn, an epilogist whom writers hire to compose suitable endings to their books. When he loses his beloved wife, Marian, in "an aeronautical event," Ben decides the right ending to their life together requires him to join her in the Other World. It's a very elaborate and confusing place, which forces Ben to hire an afterlife investigator, the Mad Hop, to help him find Marian.

The second book,

The Returned (Harlequin MIRA, due August 27), by poet Jason Mott, generated tremendous buzz at the recent Book Expo America and has received rave reviews from the four major review sources.

The tale involves people ("the Returned") who suddenly, without explanation, reappear on earth after death; they are the same age at which they died. The practical issues alone are mind-boggling, but I'm interested in the more poignant issues of mixed feelings resulting from these reappearances, and what people will decide to do about them.

I'm also excited about reading books by two authors whose previous books I loved:

The Way the Crow Flies

The Way the Crow Flies (HarperCollins, 2003) is by Canadian writer Ann-Marie MacDonald, who also wrote

Fall on Your Knees. It's a story about the destructive nature of secrets.

Members of the McCarthy family of Ontario, Canada, are happy until 1962, when Jack, a member of the RCAF, takes on the top-secret job of protecting a Soviet defector, a scientist en route to the U.S. to work for the space program. The highly moral Jack discovers that the scientist is an ex-Nazi. Meanwhile, the 8-year-old Madeleine keeps secret the molestation by a teacher at her school. Their secrets create a moral dilemma with devastating consequences when one of Madeleine's friends is murdered.

I've been looking forward to Marisha Pessl's next book since 2006, when I read her debut murder mystery,

Specialty Topics in Calamity Physics.

On August 20, Pessl's

Night Film will be published by Random House. It involves New York reporter Scott McGrath's investigation of the apparent suicide of Ashley Cordova, daughter of notorious "night film" director, Stanislas Cordova. Assisting McGrath are Holmesian "irregulars" Nora and Hopper.

Pessl uses crime as a springboard to tackle larger social issues, and her writing is very creative.

Night Film should be very fun.

My family travels a lot on weekends during the summer. Road trips mean cramped space, so my husband and I share more books than usual. Traditional mysteries stay home. Satire, sci-fi, police procedurals and nonfiction go. Before I tell you about books back on my shelves, I'll show you what I'm taking and tell you why.

I knew Martin Clark's

The Many Aspects of Mobile Home Living (Alfred A. Knopf, 2000) was a go when I read the first page and came to this:

On the morning that Evers got his first glimpse of the albino mystery, he'd been walking into the sun, scraping down the sidewalk, burping up squalls of alcohol and two-in-the-morning microwave lasagna. He had just passed by a can of garbage spilled in an alley when he thought he heard someone say his name. Evers was dizzy, the sun was sharp and combative, and he was trying hard to get to his office, so he didn't stop moving right away.

"Judge Wheeling? Sir?"

That's North Carolina Judge Evers Wheeling's introduction to car saleswoman Ruth Esther, who offers him a bribe if he'll find her brother not guilty. Of course, Evers does and then he joins a motley gang on what sounds like a trip down the rabbit's hole to Utah, on the trail of a fortune hidden by Esther's father.

Author Clark is a circuit court judge in Virginia. His legal expertise, combined with eccentric characters and vivid writing, make this black comic caper a book I can't wait to read.

My husband and I are both fans of nautical historical fiction. The Aubrey–Maturin series by Patrick O'Brian. C. S. Forester's Horatio Hornblower Saga. James McGee's

Rapscallion: A Regency Crime Thriller (Pegasus Crime, May 15), set onboard a floating prison, is irresistible.

Napoleon is at war with England in this third Matthew Hawkwood book. At the request of London's Home Secretary, Bow Street Runner Hawkwood disguises himself as an American captured fighting for the French and goes undercover to discover how prisoners of war are escaping from the

Rapacious.

No matter how sticky and uncomfortable we are in the car, we must compare favorably to those poor souls imprisoned in "gut-wrenching conditions." And this series is of the rip-roaring adventure variety. Perfect for summer.

Who didn't love the movie

In Bruges? There's no way I'll miss Pieter Aspe's English-language debut,

The Square of Revenge, published last month by Pegasus Crime. World-weary Bruges DI Pieter Van In pairs with gorgeous prosecutor Hannelore Martens to investigate an unusual jewelry store robbery. The gems weren't taken, but dumped into a tank of aqua regis, an acid so strong the gold melted. The criminals left behind a letter containing a cryptic clue. Strangely, Ludovic Degroof, store proprietor, seems more interested in covering up the crime than having it solved.

I'm always pleased to find a European crime series newly translated into English. Especially one like this, with an interesting protagonist. A lighthearted Belgian mystery, full of banter. What could be better?

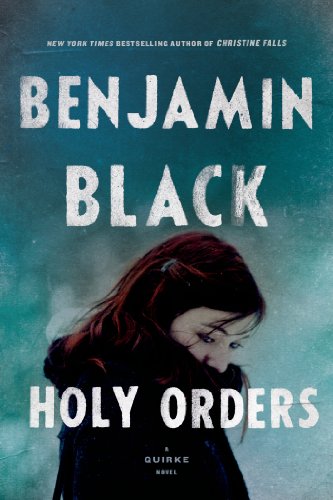

Benjamin Black's

Holy Orders: A Quirke Novel won't be released by Holt until August 20th but that will be in time for an end of summer trip over Labor Day.

After playing a supporting role to Inspector Hackett in last year's

Vengeance, Dublin pathologist Quirke returns with a case that's personal. The dead body of Jimmy Minor, a friend of Quirke's daughter Phoebe, is found floating in a canal. Hackett and Quirke must discover what story journalist Minor was working on at the time of his death.

I suspect this isn't the best book for people unfamiliar with Black's series to begin reading.

Christine Falls introduces the laconic and heavy-drinking Quirke. I like this series for its moody atmosphere, 1950s Dublin setting and the beauty of Black's prose. Black is the pen name of Booker Award winner John Banville.

I love Jo Nesbø's Harry Hole and dread the day the series ends. At least I didn't have to worry about that when I opened

The Redeemer (translated from the Norwegian by Don Bartlett), sixth in the nine-book series and re-released in the United States by Knopf in May.

The unreported rape of an unidentified girl by an unidentified boy at a Salvation Army summer camp begins a book in which the lines between right and wrong are blurred and guilt is a matter of degrees. There isn't a character who isn't looking for a form of redemption, including Nesbø's deeply flawed protagonist.

It's Christmas time in Oslo 12 years later, and Harry is investigating a drug-related death when Salvation Army volunteer Robert Karlsen is shot on the street. The Croatian hit man almost immediately realizes he's killed the wrong man, but by then Harry is on the case. Luckily for Harry, a snowstorm prevents the killer from leaving town, but he's as determined to make good on his mistake as Harry is to hunt him down. Nesbø goes into the killer's history and head to such an extent we can empathize with him. And Harry is Harry. What more does one need to say?

This is one of Nesbø's most richly detailed and intricately plotted books and not the best place to begin. I'd suggest beginning with

The Redbreast or

Nemesis.

Unlike my good friend Georgette, I feel cooler when I share my beach blanket with characters in a hot or humid setting. Hot. Humid. Mississippi.

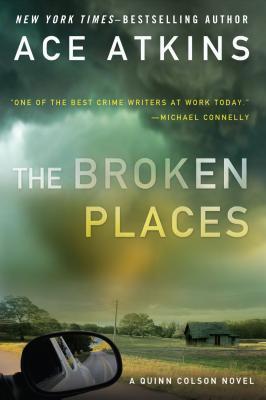

When Ace Atkins'

The Broken Places (Putnam, May 30) begins, Esau and Bones are breaking out of Parchman Prison, bound for a small town in northeast Mississippi. Already in residence is their old comrade-in-crime, Jericho native Jamey Dixon, pardoned after being convicted of killing his wife. Claiming he found Jesus at Parchman, Jamey is preaching out of a barn and romancing Caddy Colson, sister of former Army Ranger and current sheriff Quinn Colson.

Jericho is already dynamite awaiting detonation when the escaped cons arrive to accuse Jamey of cheating them out of the loot from an armored car robbery. Locals, who've never trusted Jamey, are talking vengeance. It's a perfect trifecta of trouble for Quinn when a tornado blows into town.

Ace Atkins fans already know the pleasures of reading his atmospheric Deep South books. High-wire tension, syrupy-drawling dialogue, characters you can smell and scenery you can clearly see. Quinn is an appealing character, much like Lee Child's Jack Reacher. This is the third book in the series and it's as good as the first two. No need to begin with the first,

The Ranger.

We wish we could go on forever, telling you about books we'd like to put under your noses, but we need to stop somewhere. You might want one of these for your next summer read (publication date in parentheses).

Jussi Adler-Olsen:

A Conspiracy of Faith (June 5) (translated from the Danish)

Lauren Beukes:

The Shining Girls (June 4)

Jim Crace:

Harvest (February 13)

A. S. A. Harrison:

The Silent Wife (June 25)

Stephen King:

Joyland (June 4)

Rachel Kushner:

The Flamethrowers (April 2)

Elizabeth Silver:

The Execution of Noa P. Singleton (June 11)

Carsten Stroud:

The Homecoming (July 16)

The Land of Dreams by Vidar Sundstøl

The Land of Dreams by Vidar Sundstøl So I was exhilarated to come

across The Land of Dreams, by Vidar Sundstøl (University of Minnesota, 2013). This is the first installment of his spine-chilling Minnesota Trilogy, and it is the flip side of what I was talking about.

It is a book written by a Norwegian, telling an American tale with a Norwegian

twist.

So I was exhilarated to come

across The Land of Dreams, by Vidar Sundstøl (University of Minnesota, 2013). This is the first installment of his spine-chilling Minnesota Trilogy, and it is the flip side of what I was talking about.

It is a book written by a Norwegian, telling an American tale with a Norwegian

twist. Lance is better known to

the locals as a historian and a genealogist with a great fount of knowledge

about the origins and backgrounds of the local citizenry, who are predominantly

Norwegian. Lance himself is of mixed ancestry, both Norwegian and French

Canadian. He is a divorced man in his early 40s, who lives a solitary life. He

sees his son, Jimmy, on alternate weekends and drives around with a picture of him taped on his steering wheel.

Lance is better known to

the locals as a historian and a genealogist with a great fount of knowledge

about the origins and backgrounds of the local citizenry, who are predominantly

Norwegian. Lance himself is of mixed ancestry, both Norwegian and French

Canadian. He is a divorced man in his early 40s, who lives a solitary life. He

sees his son, Jimmy, on alternate weekends and drives around with a picture of him taped on his steering wheel.

Because this is federal

land, the FBI agent, Bob Lecuyer, is in charge of the case. Eirik Nyland, a detective from the Norwegian police, also joins the team––bringing with him some Aquavit and lutefisk, which he has been assured is what everyone will expect as a gift from Norway.

Because this is federal

land, the FBI agent, Bob Lecuyer, is in charge of the case. Eirik Nyland, a detective from the Norwegian police, also joins the team––bringing with him some Aquavit and lutefisk, which he has been assured is what everyone will expect as a gift from Norway. He was

Ojibwe (known generally to the Europeans as Chippewa), and from what Lance has been

able to piece together of the history, he is certain that Caribou was murdered, most likely by

one of the small Norwegian community that existed at the time. But the secret of just what happened to Swamper Caribou has never been revealed.

He was

Ojibwe (known generally to the Europeans as Chippewa), and from what Lance has been

able to piece together of the history, he is certain that Caribou was murdered, most likely by

one of the small Norwegian community that existed at the time. But the secret of just what happened to Swamper Caribou has never been revealed.

Despite this, the Finnish

community persists to this day and their main claim to fame is St. Urho's

Day. Every year on March 16, the

day before some minor saint is celebrated for driving snakes out of Ireland,

St. Urho is celebrated for driving the grasshoppers out of Finland by saying "Grasshoppers, grasshoppers go to hell." According to Eirik Nyland, the people

in Finland have never heard of St. Urho.

Despite this, the Finnish

community persists to this day and their main claim to fame is St. Urho's

Day. Every year on March 16, the

day before some minor saint is celebrated for driving snakes out of Ireland,

St. Urho is celebrated for driving the grasshoppers out of Finland by saying "Grasshoppers, grasshoppers go to hell." According to Eirik Nyland, the people

in Finland have never heard of St. Urho. Keillor wrote this

sonnet for the bookstore opening:

Keillor wrote this

sonnet for the bookstore opening: skål

skål