|

| Disbelief that didn't maintain suspension |

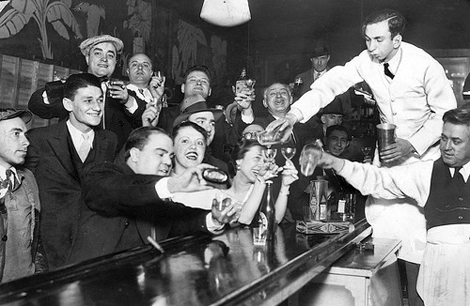

We're anticipating a pretty big storm here tonight and rain through the weekend. Living on California's Central Coast means I don't need to mount snow tires, check a backup boiler or stock the pantry with emergency food. I do need to put our patio bar stools in the garage. During a storm last winter, the wind tossed one of them against a window. That chair took flight much more easily than my disbelief while reading on occasion. Rain at night makes reading in bed mandatory. What books can I read this weekend that will keep my eyes anchored to the pages while my disbelief goes flying?

|

| Disbelief reluctant to take off |

Getting disbelief into suspension is a tricky undertaking. Sometimes, my disbelief has its heavy foot glued to the floor, and I need to concentrate harder or put the book aside for awhile to dislodge that foot. Other times, a glass of wine or leaping into the bathtub with the book does it. Occasionally, nothing I do helps. An author I love could have written the book or it could be highly recommended, but it doesn't matter. These days, 50 pages or sometimes 20 pages is enough to tell me my disbelief's flight has been cancelled. Maybe it's an act of God, and the book and I just aren't meant to be.

|

| Surprisingly, disbelief remains suspended |

|

At times, a book will drag me in and keep me there, despite some nagging residual skepticism, until the final page. Such was the case when I read Marcus Sakey's 2011 book of suspense,

The Two Deaths of Daniel Hayes. The tale opens on a beach in Maine, deserted but for a man emerging from the water:

"He was naked and cold, stiff with it, his veins ice and frost. Muscles carved hard, skin rippled with goose bumps, tendons drawn tight, body scraped and shivering. Something rolled over his legs, velvet soft and shocking. He gasped and pulled seawater into his lungs, the salt scouring his throat. Gagging, he pushed forward, scrabbling at dark stones. The ocean tugged, but he fought the last ragged feet crawling like a child."

The man spots a lonely BMW in the parking lot. Luckily, it's unlocked, and he can get in. He hits the push-button start and in a minute the heat is roaring. Inside are a map, a Rolex watch, several hundred dollars, and an almost empty bottle of Jack Daniel's. The trunk contains some dirty clothes that fit him. The glove box holds an owner's manual, some keys, and a gun. He knows it's a semiautomatic. He knows that, but he doesn't know his name. He assumes the water is the Atlantic, and by the map, that he's in Maine; yet, he doesn't know how he got there or where he came from. He studies the owner's manual and finds a registration card and proof of insurance. He decides he's Daniel Hayes, resident of 6723 Wandermere Road, Malibu, California.

Hayes drives to the nearest cheap hotel and spends a couple of nights. He watches a TV show with a female character who somehow beckons him, and his nights are filled with disturbing dreams of concrete canyons. When a cop knocks at his door, Hayes knows he must run even though he doesn't know why. Maybe he's Daniel Hayes, and maybe he'll find out more in Malibu, California.

Saying more would be a disservice, because the fun of this book is involved in accompanying Hayes as he discovers who he is and what sent him into the Atlantic. Sakey spins his tale out at a satisfying pace. It's not mentally challenging and is suitable for reading, say, when water is 20 feet away from your beach towel or drumming little drops on your window in the middle of the night.

I haven't read any of Sakey's other books.

The Blade Itself, which

Publishers Weekly awarded a starred review, is about "a horribly botched pawnshop robbery by childhood friends Evan and Danny." My disbelief's foot is tapping, so maybe I'll take a looksee.

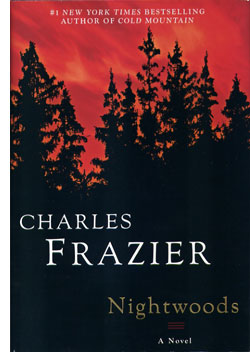

Like Marcus Sakey, Charles Frazier is an author new to me. The appearance of his

Nightwoods on a

Washington Post list of "Notable Fiction of 2011" made me curious. Upon reading the opening paragraph, my foot of disbelief scrabbled to leave the floor:

"Luce's new stranger children were small and beautiful and violent. She learned early that it wasn't smart to leave them unattended in the yard with the chickens. Later she'd find feathers, a scaled yellow foot with its toes clenched. Neither child displayed language at all, but the girl glared murderous expressions at her if she dared ask where the rest of the rooster went."

At its heart, this book is about moving forward despite "whatever trail of ashes are left behind." Life goes one way only: "Nothing changes what already happened. It will always have happened. You either let it break you down or you don't."

Luce has chosen not to let it break her down. When the book begins, it is the 1960s, and she is a beautiful young woman who has taken refuge from life's hard knocks as the caretaker of the Lodge, an abandoned old hotel in the Appalachians of North Carolina. Luce is the daughter of Lola, who had a free-range philosophy about child raising and warned Luce and her sister Lily never ever to cry before she disappeared while they were still in elementary school, and Lit, a bantam-size deputy sheriff who is likened to a mink in a hen house and who has a fondness for substances that make him feel "up."

Luce lives across the lake from town, and her days are rather lonely, but she is content, watching the seasons change, observing the creatures in the woods, and reading the books in the hotel's library. Her isolation is broken by the appearance of her sister Lily's young twins, Delores and Frank. Lily has been murdered by her husband Bud, under the eyes of these children, and Luce is now their guardian. The twins are traumatized and mute; they love setting fires and getting themselves into trouble. But, "[b]eing uncommunicative and taking an interest in fire were neither crimes nor sins, just inconvenient. And Luce didn't have to love them. She just had to take care of them."

Taking care of Frank and Delores, and Luce's life in general, are made more complicated when Bud, whose murder trial stuttered to a halt when two jurors voted not guilty, moves to town so he can look for money he thinks Lily had and keep a nasty eye on the twins. Young Stubblefield, who knew Luce in high school and inherited the Lodge when his grandfather died, shows up, too. The main cast is now complete, and life will go forward.

Nightwoods is a literary book. It's a compelling narrative told by a southerner with a writing style that makes one think of the words "trance," "molasses," and "baroque." Frazier's characters are all memorable, and what they do is worth watching. Sometimes the prose tends to the purple, but I had no desire to stop reading. If you love the woods, as I do, you'll probably enjoy Frazier's knowledge and feel for those dark and mysterious places. I liked the book, and I'm going to look for his

Cold Mountain, a story about a wounded Confederate deserter who walks for months to return to the love of his life, and

Thirteen Moons, set in the mid-19th century and based loosely on the life of William Holland Thomas.

|

| Disbelief well suspended |

These are a couple of the books that kept my disbelief suspended during the past few days. On my bedside table for my rainy night reading are

The Shadow of the Shadow by Paco Ignacio Taibo II, a historical fantasy that I've been saving for a special treat because a friend raved about it; Michael Kortya's

The Ridge, a 2011 thriller set in the woods of eastern Kentucky; Tom Perrotta's 2011 book,

The Leftovers, involving a mass disappearance called the Sudden Departure; and

Gerontius by James Hamilton-Paterson, who made me laugh out loud with his wonderful satire set in Tuscany,

Cooking with Fernet Branca. When I read

Gerontius, I'll head up the Amazon with Sir Edward Elgar, a distinguished composer. Other books that took me to Amazon territory are Ann Patchett's

State of Wonder and David Grann's

The Lost City of Z, and I recommend both of them.

Disbelief is an unpredictable thing. I'd love to hear about the books that are kept your disbelief suspended and those that didn't, and why.

|

| Disbelief following a moving plot |