Yesterday began a week of Dali Time at my house. That's what my husband and I call our kids' obsession with time since Daylight Saving Time ended and we set the clocks back an hour on Sunday morning. I cannot say, "Lunch is at 1:00," without their response, "You mean Now Time or Real Time?" as if we're time traveling, or any moment the hands on the clock will spring forward again. They heatedly debate what time it really is until my head spins. This is when I'd take refuge in a book, but if the book is anything like some I've read recently, time doesn't stay put there either.

Yesterday began a week of Dali Time at my house. That's what my husband and I call our kids' obsession with time since Daylight Saving Time ended and we set the clocks back an hour on Sunday morning. I cannot say, "Lunch is at 1:00," without their response, "You mean Now Time or Real Time?" as if we're time traveling, or any moment the hands on the clock will spring forward again. They heatedly debate what time it really is until my head spins. This is when I'd take refuge in a book, but if the book is anything like some I've read recently, time doesn't stay put there either.The past collides with the present through memories and visions in The Fire Witness, a riveting and spooky thriller by Lars Kepler (translated from Swedish by Laura A. Wideburg), published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in July 2013.

The crime scene at a home for troubled girls in Sundsvall, Sweden, is disturbing. A ward nurse and teenage resident were bludgeoned to death. The bloody weapon is found under Vicky Bennett's pillow, but Vicky has vanished into the forest, only to reappear and steal a car with a young child asleep in the backseat. The case is closed when the empty car turns up in the river. But Stockholm Detective Inspector Joona Linna doesn't believe Vicky and little Dante are dead and he isn't convinced of Vicky's guilt. No one trusts Linna's instincts, because he's still off-kilter from an internal affairs investigation and worries about his family's safety. Then he receives a call from medium Flora Hansen, who insists this time her visions are real.

Time, logic and and identity shift in César Aira's The Hare (translated by Nick Caistor), published in July 2013 by New Directions.

Nineteenth-century British naturalist/explorer Tom Clarke is in the Argentine pampas, searching for the mythical leaping and flying Legibrerian hare. Accompanying him are a gaucho with plans of his own and a 15-year-old boy. Their mission is interrupted when Cafulcura, leader of the Mapuche tribe, disappears and Clarke assumes the role of detective responsible for finding him. An all-out tribal war ensues.

That makes too much sense to convey the tangle of subplots, the sense of improvisation and strange conversations in which the meaning of words changes as they are spoken. Despite the wild and woolly disorder, it ties together in a meaningful way. You'll want to read this if you have an appetite for imaginative and absurd Victorian adventure.

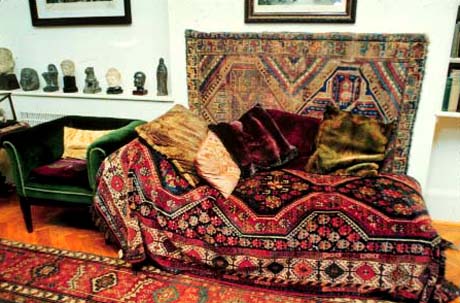

After a decade of quietly observing the ravages of time, a guard at London's National Gallery becomes restless with her stalled life.

In Chloe Aridjis's hypnotic modern Gothic, Asunder (September 2013, Mariner Books/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), Marie is the 33-year-old guard. Her great-grandfather was also a museum guard there and his inability to stop suffragette Mary Richardson's vandalism of Velàzquez’s Rokeby Venus haunted him and weighs on Marie. Almost as quiet as her work is her life outside the museum, hanging out with her roommate and creating tiny landscapes inside eggshells. A trip to Paris with her poet friend Daniel tears her life asunder.

The asides, such as the explanation of why varnish on painted canvas forms a network of cracks ("craquelure"), are fascinating. The beauty of the writing about the effects of time invites margin notes and underlining. This is a book I'll remember.

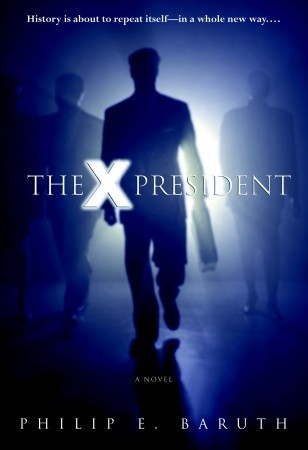

Let's leap four decades into the future with a U.S. President from our past, and then travel back in time to the '60s.

Let's leap four decades into the future with a U.S. President from our past, and then travel back in time to the '60s.It's 2055 in Philip E. Baruth's satire/sci fi/thriller The X President. Several bills signed by then-President Bill Clinton in the 1990s have now resulted in decades of global Tobacco Wars. The war isn't going well for our country, and the National Security Council has the answer. Surprisingly, it isn't drones or spying on Americans, our enemies and our friends. They want to time travel to 1995 and undo those Clinton decisions. To this end, they kidnap Sal Hayden, the official biographer of now 109-year-old "BC" (it's due to bionics, not veganism) and send Sal back to 1963 to find the 16-year-old "yBC." Accompanying Sal are NSC operatives code-named "George" (Stephanopoulos), "James" (Carville) and "Virginia" (yes, she's beautiful). It's kinda silly but who doesn't like (a) time travel, (b) satire/thrillers and (c) BC? (Hey, if you can't say anything nice....)

I often correct my kids' manners with that reminder, and now that reminds me. It might be time for my kids to go to bed. That is, if it's really their bed time.

+Lange.jpg)