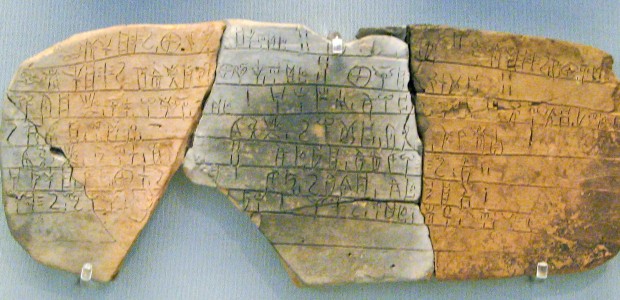

Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, thought to be written in the eighth century B.C., are among the oldest written works of Western literature we know. Imagine the excitement, then, when hundreds of clay tablets were discovered on the island of Crete, and they were dated back to sometime between 1400 and 1450 B.C.; in other words, hundreds of years before Homer did his work and even before the battle of Troy he described.

During the Victorian era, the sun never set on the British Empire––as you may have heard––and Victorian gentlemen trampled all over the empire and the world digging up artifacts of ancient civilizations. In 1900, one of these gentlemen, Arthur Evans, discovered a huge, ruined palace on Crete, where the clay tablets were preserved by fire after the palace was apparently sacked and torched.

Some of the symbols on the tablets were pictograms, lovely little representations of horses, for example. Mostly, though, the characters were a mystery. Nobody knew what language was used on Crete at the time the tablets were written, and the symbols that weren't pictograms were just tantalizingly ornate hints of life in this long-ago civilization.

Some of the symbols on the tablets were pictograms, lovely little representations of horses, for example. Mostly, though, the characters were a mystery. Nobody knew what language was used on Crete at the time the tablets were written, and the symbols that weren't pictograms were just tantalizingly ornate hints of life in this long-ago civilization. Margalit Fox tells the story of the three preeminent figures in the life of "Linear B," as Evans called the script found on the tablets. Evans, the archeologist whom Fox calls "The Digger"; Alice Kober, an assistant professor of Classics at Brooklyn College, who spent most of the 1940s sitting at her kitchen table painstakingly making note cards, charts and graphs to crack the code of Linear B; and Michael Ventris, the precocious English polymath with a prodigious systematic memory, who made the final breakthrough discoveries that allowed the mystery of Linear B to be solved.

Margalit Fox tells the story of the three preeminent figures in the life of "Linear B," as Evans called the script found on the tablets. Evans, the archeologist whom Fox calls "The Digger"; Alice Kober, an assistant professor of Classics at Brooklyn College, who spent most of the 1940s sitting at her kitchen table painstakingly making note cards, charts and graphs to crack the code of Linear B; and Michael Ventris, the precocious English polymath with a prodigious systematic memory, who made the final breakthrough discoveries that allowed the mystery of Linear B to be solved.Although most of the action in this book consists of these three sitting at tables, in solitary, obsessive pursuit of the key to a long-dead language and civilization, this is still a gripping adventure story. Anyone who has an interest in codes and cryptography will be riveted by Fox's descriptions of the methodology and thought processes that Kober and Ventris, in particular, used. With so much of the work taking place during World War II, paper rationing forced Kober to use cigarette cartons for file card holders and scraps of reused greeting cards and receipts as note cards. Ventris was a navigator on RAF bombers, and on trips back to England after bombing runs, he sometimes used his large map table in the the bomber to spread out his research cards and continue his work.

Each small step forward in the quest to solve Linear B is thrilling, though it's also sad to see how much of the rest of their lives Kober and Ventris sacrificed. Kober fell ill and died in 1950, when she might have been within a few more months or years of cracking the code. After being the one to make the final victory in 1952, Ventris seemed to feel his life had lost its meaning, and he died in a mysterious car wreck shortly thereafter.

Each small step forward in the quest to solve Linear B is thrilling, though it's also sad to see how much of the rest of their lives Kober and Ventris sacrificed. Kober fell ill and died in 1950, when she might have been within a few more months or years of cracking the code. After being the one to make the final victory in 1952, Ventris seemed to feel his life had lost its meaning, and he died in a mysterious car wreck shortly thereafter.Evans, Kober and Ventris never thought they were working on some great, recovered work of literature. They knew that the tablets were, essentially, municipal records. These were inventories of livestock and produce, and records of transactions. But no matter how prosaic their subject matter, as Fox notes, the tablets "disclose the day-to-day workings of a civilization three thousand years distant" and allow us to imagine these very real people so long ago, on that sunstruck rock in the Mediterranean.

|

| Alice Kober's Linear B card files |

how Alice Kober, because of her sex, was never given her due for her groundbreaking work on Linear B, with claims that she was ignored in the 1940s and forgotten now. To be fair, Fox's own introduction to the book, as well as a couple of pages at the end, seem to take this tack. But the bulk of the book doesn't really bear this out. Fox describes in detail Kober's correspondence with the big names of her time who were active in the world of Linear B, her winning a Guggenheim Fellowship to further her work, her well-received academic publications, and Ventris's acknowledgment of the firm foundation Kober created that allowed him to reach his goal. If I hadn't read the introduction, the book would never have given me any idea that Kober was ignored or forgotten.

I suspect this whole notion that sexism caused Kober to be ignored and forgotten has been added on as a sort of marketing ploy––though with Fox's apparent acquiescence, given that introduction. My guess is that Kober would have dismissed that whole notion as a distraction. Judging from the correspondence quoted in this book, for her, it was always all about the work, not the personal. And in this case, the work of Kober and Ventris is what makes this book special. (I didn't find Evans's story, which takes up about one-quarter of the book, nearly as interesting as the rest of the story; possibly, because he didn't seem to have a clue about how to go about analyzing the script.) The descriptions of the methodology can be tough going at times, but this adventure in history, linguistics, cryptography and archeology is worth the effort.

* * *

Pop Quiz

I got a kick out of one small part of the book in which Margalit Fox uses a quiz to give us just a slight flavor of the process of figuring out what symbols might mean on a found language tablet. The job with figuring out Linear B was far, far more complex, of course. So just look at the following as a puzzle for entertainment.

The following 11 symbols are from the ideographic language Blissymbols, created by Charles K. Bliss and intended to be a universal written language that speakers of different languages could use to communicate with each other. Fox explains that at the 2010 International Olympiad of Linguistics, these symbols were used in a competitive quiz.

|

| Top row: Symbols 1-6; bottom row: Symbols 7-11 |

Use your linguistics or cryptographic skills to match each of the symbols above with the appropriate word below:

waist, active, ill/sick, activity, to blow, western, merry, to weep, saliva, to breathe, lips.

It can be done with no further information. When I tried it, I admit I blew the answers to two of them, but I felt confident about the other nine as I worked them out.

Did you figure it out? Do you need a hint? If so, here's your hint (highlight the following text to read the hint):

group the words by parts of speech and see if there are visual cues in the symbols to indicate parts of speech.

If the hint's not enough, or you've finished your work on the quiz, here are the answers and an explanation.

The words are four nouns, four adjectives and three verbs. Four of the symbols have "v" carets on top and three have "tent" carets on top, so that's a clue that the three symbols with the tent carets are the verbs.

Your next clue is that "activity" and "active" are related words, so we look for two symbols in which one is the same as the other except for a caret. That's true of #10 and #4. We don't know which is which, though, so we need to figure out whether the "v" caret indicates a noun or an adjective.

Take a look at the symbols with "v" carets. Of the four possible nouns and four possible adjectives, doesn't it seem most likely that the last symbol, the one with the heart and the upward arrow, would stand for "merry"? If so, all the signs with "v" carets are adjectives and #4 would be "active," while #10 would be the noun, "activity." This also tells us that nouns are the symbols with no carets on top.

At this point, we have three still-unidentified nouns: waist, lips and saliva. The latter two have to do with the mouth, and two of the symbols have little circles: #2 and #8. So that likely means that the remaining noun symbol, #5, is "waist." Just from the look of the symbols, we can guess that #2 is "saliva" and #8 is "lips."

We have two still-unidentified adjectives: #3 and #7. Which is "sick" and which is "western"? (This is the one I had a hard time with and ultimately got wrong.) The big circle stands for the sun and the directional caret over the sun points west, so #3 is "western."

That leaves us with the three verbs; the symbols with the tent carets on top. Two of those verbs have to do with the mouth, and we already know that the mouth is symbolized by the small circle. Of the three symbols left, one has a small circle with a dot in the middle, and it has a downward arrow with it. So that one, #9, should be "to weep." Number 1 and #6 must be "to breathe" and "to blow," then, and since #6 looks like it's almost the same as #1, but with a directional arrow, it's logical to conclude that #1 is "to breathe" and #6 is "to blow."

In summary, then:

The first symbol is a verb, composed of the symbols for nose + mouth: to breathe.

The second symbol is a noun, composed of the symbols for water + mouth: saliva.

The third symbol is an adjective, composed of the symbols for sun + a pointer: western.

The fourth symbol is an adjective, composed of the symbol for activity, plus the indicator for an adjective: active.

The fifth symbol is a noun, composed of the symbols for body (torso) and two pointers: waist.

The sixth symbol is a verb, composed of the symbols for mouth + (air+outwards): to blow.

The seventh symbol is an adjective: ill/sick.

The eighth symbol is a noun, composed of the symbols for a mouth and two pointers: lips.

The ninth symbol is a verb, composed of the symbols for eye + (water+downwards): to weep.

The tenth symbol is a noun: activity.

The eleventh symbol is an adjective, composed of the symbols for heart + upwards: merry.