Cheaply-made pistols, an old pamphlet headlined

Libération, a leather suitcase with a striped prisoner's uniform and photographs of prisoner-number tattoos inside. These are objects that open the door into a painful past for characters in two new World War II novels of mystery and suspense.

Book Review of Peter Steiner's

The Resistance

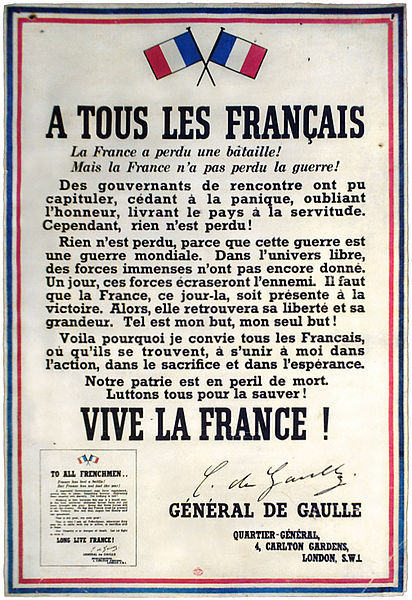

We begin in the Nixon era, with CIA agent Louis Morgon suddenly being axed from his job. Knocked for a loop, he leaves his life behind and moves to a small village, Saint-Léon-sur-Dême, in France. While fixing up the decrepit cottage he's purchased, he finds a cache of weapons and French Resistance pamphlets. He takes them to Saint-Léon's lone gendarme, young Jean Renard. Renard has lived in Saint-Léon all his life, and his father, Yves, was the village's gendarme during World War II.

Yves Renard, like many other villagers, won't talk about the war. Jean Renard has heard rumors that Yves was a collaborator; that, as a gendarme, he did the bidding of the occupiers. Helping Louis investigate the cache provides Jean with an opportunity to delve into the history of Saint-Léon in wartime, and a present-day murder breaches the villagers' wall of silence about the war.

After a brief couple of chapters introducing us to Louis Morgon, Jean Renard and the finding of the cache, we are transported back to the war and the story of Saint-Léon's residents. We meet the village's mayor and councilmen, Yves Renard, young farmers Onesime and Jean, and their mother Anne-Marie, the widow Troppard, Count Maurice de Beaumont and his wife Alexandre, and many other locals, as well as a shadowy Resistance organizer code-named Simon. The villagers take sides in a secret and deadly game of chess; one where a player can't be sure whether the others are playing black or white––or maybe both.

The Resistance's subtitle, "A Thriller," is a little misleading and may do this book a disservice. Although there is plenty of intrigue and tension in the plot, it's no bang-bang, action-driven story. The focus is on the secrets and lies forced upon the villagers by the occupation, the moral compromises they must make, and the effect these have on their relationships with their neighbors and loved ones. The pace is measured and deliberate. We have time to watch the seasons pass; to see birth, death and rebirth.

From a historical viewpoint, this is an insightful treatment of the development of resistance. After France was so quickly defeated, most hoped that life could go on as before. Many were eager to cooperate with the occupiers; at least the occupation ensured that the Communists would not take over, they thought. Others had political and moral convictions that led them to resist from the start. The immediate resisters-from-conviction, and the unreflective collaborators, are not Steiner's focus. He shows us, instead, ordinary people and the difficult individual choices they make. This is a subtle and sympathetic treatment of the moral complexities of life under occupation.

The Resistance was published in 2012 by Minotaur Books. I recommend it for readers who enjoyed Martin Walker's

Bruno, Chief of Police and Sebastian Faulks's

Charlotte Gray.

* * * * *

Book Review of Greg Dinallo's

The German Suitcase

Stacey Dutton, a young go-getter at a New York ad agency, spots an old, high-end leather suitcase among the discarded storeroom belongings from a grand Manhattan apartment building being converted to condos. Her agency represents Steinbach & Co., the maker of the suitcase, and Stacey is inspired to grab the suitcase for use in an ad campaign. When it's found that the suitcase belongs to a prominent doctor and pillar of New York philanthropy, who is also a Holocaust survivor, the suitcase becomes much more than a prop in an ad campaign. But when Stacey's boyfriend, a

New York Times reporter, finds discrepancies between the doctor's story and the artifacts found in the suitcase, a mystery tale begins.

In alternating chapters, we travel between contemporary New York, and Munich during the last year of World War II, where three friends are surgeons in a hospital, treating military and civilian victims of war wounds. This is an unlikely friendship, considering that one, Max Kleist, is an officer in the Waffen-SS, while Eva Rosenberg and Jacob Epstein are Jews working under an extremely rare exemption from the Nazi state's laws that forbade Jewish doctors to treat Aryan patients. This exemption is abruptly yanked, and Jake and Eva must go on the run to avoid falling into the Nazis' genocidal machine. Max, whose close relationship with his Jewish colleagues is known, and whose prominent family is suspected of working underground to help victims of Nazi persecution, is sent to serve as a medical officer at the Dachau extermination camp.

For Germany during World War II, Nazism and the cult of Hitler supplanted all other loyalties and beliefs. Soldiers swore fealty not to the Fatherland, but to Adolf Hitler personally. Formerly devout Catholics and Protestants converted to a faith in Nazism's confused melding of Nordic mythology and racial destiny. Even scientific truths were corrupted by Germany's new dogma of racialism, with its virulent anti-Semitism and belief in the superiority of Aryans. At Dachau, Max finds himself in an environment where he is expected to pervert his Hippocratic oath in the service of these twisted beliefs and aims. His family and his own destiny are held hostage to his choices.

There are some weaknesses in the book. The present-day characters lack the dimensionality of the World War II characters. The conclusion doesn't live up the promise of the rest of the book. A plot twist is obvious (to die-hard mystery readers, anyway) almost from the get-go. The writing in the early part of the book is overburdened with adjectives and adverbs, which bogs down the pace and makes it feel like the author is trying too hard. Fortunately, he snaps out of this and the writing becomes clean and assured. Despite its flaws, I recommend this book to the readers of World War II-era novels. Author Greg Dinallo poses difficult questions about moral choices in impossible circumstances, and challenges our black-and-white views of World War II survivors. The topic of doctors in Nazi Germany is particularly interesting, and one that is not often the focus of World War II fiction. Above all, the stories of Max, Jake and Eva are gripping.

Greg Dinallo is a former filmmaker and television and movie writer. He turned to novel writing 20 years ago and, before

The German Suitcase, published five thrillers, including

Red Ink, which was named a

New York Times Notable Book.

The German Suitcase is Dinallo's first digital-only title, published in 2012 by Premier Digital Publishing.

Disclosure: I received a free publisher's review copy of

The German Suitcase.

Note: Versions of these reviews may appear on Amazon and other reviewing sites under my user names there.

I found a gray hair. On our dog. My husband's birthday is coming up. I dragged out my mom's old iron skillet and was in the middle of making corn bread when I realized my baking powder had expired. It seems as if old age is closing in from all directions. Even my books yell "Old!" Take a look at my recent reading and you'll see characters who aren't spring chickens. Or the books themselves are middle-aged, or set in the distant past. Of course, there's no expiration date on excellence when it comes to the written word.

I found a gray hair. On our dog. My husband's birthday is coming up. I dragged out my mom's old iron skillet and was in the middle of making corn bread when I realized my baking powder had expired. It seems as if old age is closing in from all directions. Even my books yell "Old!" Take a look at my recent reading and you'll see characters who aren't spring chickens. Or the books themselves are middle-aged, or set in the distant past. Of course, there's no expiration date on excellence when it comes to the written word. Becky Masterman: Rage Against the Dying (2013). There's Clarice Starling and now there's retired FBI Special Agent Brigid Quinn. Brigid is married to an ex-priest and settled in Tucson, Arizona, when she learns that the Route 66 killer, involved in the disappearance of her protégé, has been captured. But maybe not. The beginning, in which a predator sizes up his prey, nearly creeped me out but I'm glad I persevered. Brigid, at age 59, kicks ass better than she cooks dinner.

Becky Masterman: Rage Against the Dying (2013). There's Clarice Starling and now there's retired FBI Special Agent Brigid Quinn. Brigid is married to an ex-priest and settled in Tucson, Arizona, when she learns that the Route 66 killer, involved in the disappearance of her protégé, has been captured. But maybe not. The beginning, in which a predator sizes up his prey, nearly creeped me out but I'm glad I persevered. Brigid, at age 59, kicks ass better than she cooks dinner. Peter Steiner: The Terrorist (2010). Retired CIA Middle East expert Louis Morgon, who's living in France and dealing with cancer, is coerced by the imprisonment of a young friend into rejoining his old employer's war on terror. This is unusually character-driven espionage and also a beautifully written novel about relationships and mortality. The next book in the series, The Resistance, is reviewed by Sister Mary Murderous here.

Peter Steiner: The Terrorist (2010). Retired CIA Middle East expert Louis Morgon, who's living in France and dealing with cancer, is coerced by the imprisonment of a young friend into rejoining his old employer's war on terror. This is unusually character-driven espionage and also a beautifully written novel about relationships and mortality. The next book in the series, The Resistance, is reviewed by Sister Mary Murderous here. Paul McEuen: Spiral (2011). Scientific thriller fans, make a note. Cornell physicist McEuen wrote what he knows in an exciting and thought-provoking doomsday thriller. His debut combines nanotechnology, biological engineering and Japanese WWII history. I hated to see Nobel Prize winner and Cornell Professor Emeritus Liam Connor leap off an Ithaca bridge to his death, but I enjoyed the investigators: Connor's physics department colleague Jake Sterling, his granddaughter Maggie and her nine-year-old son Dylan.

Paul McEuen: Spiral (2011). Scientific thriller fans, make a note. Cornell physicist McEuen wrote what he knows in an exciting and thought-provoking doomsday thriller. His debut combines nanotechnology, biological engineering and Japanese WWII history. I hated to see Nobel Prize winner and Cornell Professor Emeritus Liam Connor leap off an Ithaca bridge to his death, but I enjoyed the investigators: Connor's physics department colleague Jake Sterling, his granddaughter Maggie and her nine-year-old son Dylan. Michael Gilbert: Fear to Tread (1953). Gilbert wrote one intelligent mystery after another for decades. His best-known Inspector Hazelrigg book is probably Smallbone Deceased, but this is another good one. Wilfred Wetherall is a boys' school headmaster in post-WWII London. He carries on in good British fashion by resolutely tackling every problem, including a ring of vicious black marketeers. It's a very satisfying read.

Michael Gilbert: Fear to Tread (1953). Gilbert wrote one intelligent mystery after another for decades. His best-known Inspector Hazelrigg book is probably Smallbone Deceased, but this is another good one. Wilfred Wetherall is a boys' school headmaster in post-WWII London. He carries on in good British fashion by resolutely tackling every problem, including a ring of vicious black marketeers. It's a very satisfying read. John Mortimer: Forever Rumpole: The Best of the Rumpole Stories (2011). Let's raise a glass of Pommeroy's best plonk to the memory of Mortimer, who died in 2009, and his Old Bailey hack, Horace Rumpole. The 14 stories in this collection aren't new, but there's a new introduction by Anna Mallalieu––who knew Mortimer personally and professionally when he was Queen's Counsel––and a new piece of an unfinished novel, "Rumpole and the Brave New World." Reading Rumpole is one of the best ways to counter feeling old. Whether he's defending a member of the criminous Timson family, talking with colleagues in chambers or parrying the commands of his wife Hilda ("She Who Must Be Obeyed"), Rumpole is ageless in his optimism and enthusiasm for a good battle.

John Mortimer: Forever Rumpole: The Best of the Rumpole Stories (2011). Let's raise a glass of Pommeroy's best plonk to the memory of Mortimer, who died in 2009, and his Old Bailey hack, Horace Rumpole. The 14 stories in this collection aren't new, but there's a new introduction by Anna Mallalieu––who knew Mortimer personally and professionally when he was Queen's Counsel––and a new piece of an unfinished novel, "Rumpole and the Brave New World." Reading Rumpole is one of the best ways to counter feeling old. Whether he's defending a member of the criminous Timson family, talking with colleagues in chambers or parrying the commands of his wife Hilda ("She Who Must Be Obeyed"), Rumpole is ageless in his optimism and enthusiasm for a good battle. David Lawrence: The Dead Sit Round in a Ring (2004). Compelling blackest noir written under a pseudonym by acclaimed English poet David Harsent. Three elderly siblings, who must have formed a suicide pact, and an unidentified man are found dead in a London apartment. As if Det. Sgt. Stella Mooney doesn't have enough of a headache with her private life, there's this complex crime. This is the debut of a gritty English police procedural series featuring a tough and attractive female cop.

David Lawrence: The Dead Sit Round in a Ring (2004). Compelling blackest noir written under a pseudonym by acclaimed English poet David Harsent. Three elderly siblings, who must have formed a suicide pact, and an unidentified man are found dead in a London apartment. As if Det. Sgt. Stella Mooney doesn't have enough of a headache with her private life, there's this complex crime. This is the debut of a gritty English police procedural series featuring a tough and attractive female cop. Michael Innes: A Night of Errors (1947). Over-the-top frolicking from Innes. Sir John Appleby, retired from New Scotland Yard, investigates the bizarre fireplace death of Sir Oliver Dromio, who followed family tradition by burning to a crisp. Appleby and Inspector Hyland do a full night's work, combing through the many suspects' motives. Bodies litter the landscape before it's over and the case draws to a close in this eleventh of 35 Appleby books. Very entertaining.

Michael Innes: A Night of Errors (1947). Over-the-top frolicking from Innes. Sir John Appleby, retired from New Scotland Yard, investigates the bizarre fireplace death of Sir Oliver Dromio, who followed family tradition by burning to a crisp. Appleby and Inspector Hyland do a full night's work, combing through the many suspects' motives. Bodies litter the landscape before it's over and the case draws to a close in this eleventh of 35 Appleby books. Very entertaining. Laura Joh Rowland: Red Chrysanthemum (2006). A blood-soaked chrysanthemum is the only clue samurai investigator Sano Ichirō has to clear his wife Reiko of suspicion in the murder of Lord Mori. This is Rowland's eleventh book set in feudal Japan. It's wonderfully atmospheric and features her usual graceful writing and deft characterization.

Laura Joh Rowland: Red Chrysanthemum (2006). A blood-soaked chrysanthemum is the only clue samurai investigator Sano Ichirō has to clear his wife Reiko of suspicion in the murder of Lord Mori. This is Rowland's eleventh book set in feudal Japan. It's wonderfully atmospheric and features her usual graceful writing and deft characterization. Alana White: The Sign of the Weeping Virgin (2012). The title sounds like a Perry Mason case, but it's historical fiction set in 1480 Italy. Real-life Florentine lawyer Guid'Antonio Vespucci and his nephew Amerigo (who later explored and donated his name to the New World) have barely returned from a diplomatic mission in France before they're embroiled in Florentine politics and investigations of a kidnapping and a painted Virgin Mary that seems to be weeping. White's knowledge and wit, and the presence of the Vespuccis, Boticelli, da Vinci, the Medici family and other Renaissance figures, make this book a fun Italian trip.

Alana White: The Sign of the Weeping Virgin (2012). The title sounds like a Perry Mason case, but it's historical fiction set in 1480 Italy. Real-life Florentine lawyer Guid'Antonio Vespucci and his nephew Amerigo (who later explored and donated his name to the New World) have barely returned from a diplomatic mission in France before they're embroiled in Florentine politics and investigations of a kidnapping and a painted Virgin Mary that seems to be weeping. White's knowledge and wit, and the presence of the Vespuccis, Boticelli, da Vinci, the Medici family and other Renaissance figures, make this book a fun Italian trip.