|

| Abolitionist John Brown |

The Good Lord Bird by James McBride

The Good Lord Bird by James McBrideThe mistake central to McBride's The Good Lord Bird (August 2013, Riverhead) happens like this: It's 1856, and white abolitionist John Brown has his rifle trained on angry Pro Slavers (people who are pro-slavery) inside Dutch Henry's Tavern in Kansas Territory. All the blacks have hauled ass home, except for our narrator, then 10-year-old mulatto Henry Shackleford, and his pa, both slaves. Henry, like other black boys his age, wears a potato sack. "You and your daughter is now free," Brown says. Pa only manages, "Henry ain't a," before he is killed accidentally. Brown grabs Henry and runs, and thus begins Henry's—or Henrietta's—17 years as a black woman and the story of how he came to be the only black survivor of Brown's ill-fated raid on the federal armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859.

|

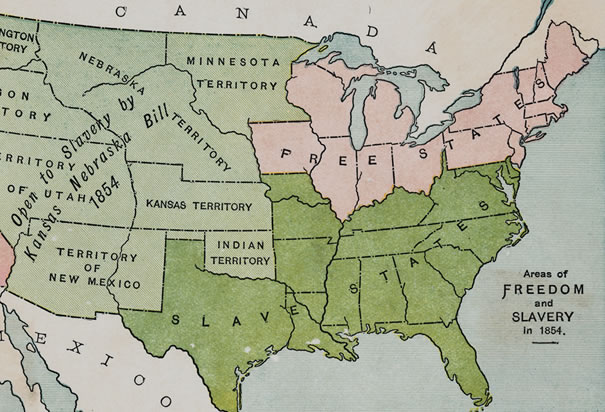

| Missouri, a slave state, shares a border with Kansas Territory |

Before continuing with Henry's story, a little history is in order. When Kansas Territory was created by the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, the question of slavery in Kansas was left up to popular sovereignty. Unfortunately, pro-slavery Border Ruffians from the neighboring slave state of Missouri took this as an invitation to force the acceptance of slavery onto Kansans through terrorism and fraud. Most whites in Missouri were too poor to own slaves, but they hated Yankees and abolitionists and feared more free blacks living nearby. In addition, they knew that if Kansas were admitted to the Union as a free state, the balance of anti- and pro-slavery representation in the U.S. Senate would be disrupted.

Between 1854 and 1861, when free-state Kansas gained admission to the Union, there were so many violent confrontations in Kansas Territory that spilled over into western Missouri, the Territory was called "Bleeding Kansas." Most Kansas Free Staters weren't abolitionists, but they were forced to fight back against Pro Slavers.

Between 1854 and 1861, when free-state Kansas gained admission to the Union, there were so many violent confrontations in Kansas Territory that spilled over into western Missouri, the Territory was called "Bleeding Kansas." Most Kansas Free Staters weren't abolitionists, but they were forced to fight back against Pro Slavers.Abolitionist John Brown had several adult sons living in Kansas Territory, and he left his wife and other children (of 22 children, 12 were still living) in upstate New York to join them. Several events in 1856 helped persuade Brown that he "couldn't have a sit-down committee meeting with the Pro Slavers and nag and commingle and jingle with 'em over punch and lemonade and go bobbing for apples with 'em" to eradicate slavery: Pro Slavers sacked Lawrence, Kansas, and South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks was proclaimed a hero in the South after he caned Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner for delivering a U.S. Senate speech in which he likened Border Ruffian violence in Kansas Territory to the rape of virgins.

Enough background history. The Good Lord Bird is rollicking tragicomedy/historical fiction that follows Old John Brown, narrator Henry (AKA "the Onion" after "she" unthinkingly ingests Brown's lucky onion and becomes Brown's walking good luck charm), and Brown's ragtag band of sons and assorted followers from their murderous attack on a Pro Slaver's homestead to battles at Black Jack and Osawatomie before the Onion is left at a Pikesville, Missouri whorehouse while Brown heads back East to fundraise, and his men disperse. After surviving several years working for whorehouse madam/businesswoman Miss Abby and the budding of understandable adolescent boy yearnings for a beautiful prostitute named Pie, Onion is back on the trail with Brown.

Enough background history. The Good Lord Bird is rollicking tragicomedy/historical fiction that follows Old John Brown, narrator Henry (AKA "the Onion" after "she" unthinkingly ingests Brown's lucky onion and becomes Brown's walking good luck charm), and Brown's ragtag band of sons and assorted followers from their murderous attack on a Pro Slaver's homestead to battles at Black Jack and Osawatomie before the Onion is left at a Pikesville, Missouri whorehouse while Brown heads back East to fundraise, and his men disperse. After surviving several years working for whorehouse madam/businesswoman Miss Abby and the budding of understandable adolescent boy yearnings for a beautiful prostitute named Pie, Onion is back on the trail with Brown.They head to Boston, where Brown introduces fundraising speeches with "I'm John Brown from Kansas, and I's fighting slavery." Onion hates speechifying without "joy juice," but she tells stories about how hungry and miserable she was as a slave, which are lies, since the only starving she's ever done has been in the company of Brown, who never seems to eat, and his dozen men, who sometimes dine on one measly squirrel while listening to Brown bark and pray and howl at his Holy Redeemer for hours until his son Owen, the only one who dares, stops him with a "Pa! The Pro Slavers posse (or U.S. cavalry) is coming!" Raising funds is very difficult for Brown, because white Northerners sympathetic to his anti-slavery cause want to know exactly what he plans to do with their money, and Brown, fearing U.S. government spies, refuses to divulge his plans.

| Old John Brown was feared and hated by Pro Slavers and revered by blacks and fellow abolitionists |

|

| Author James McBride |

Given McBride's entertaining and insightful portraits of fictional blacks like Onion, Pie, and a slave named Sibonia; and the real-life Brown, his sons, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman, I wasn't surprised when The Good Lord Bird won the National Book Award this year. I strongly suggest it to people who enjoy historical fiction like John Barth's romp, The Sot-Weed Factor, in which failed English poet Ebeneezer Cooke, his sister, and their tutor travel to Maryland in the 1700s; E. L. Doctorow's Ragtime, in which we meet historical figures such as Harry Houdini in turn-of-the-century New York City; and Dennis Lehane's atmospheric The Given Day, which centers around a Boston cop's family in early 20th-century Boston.

Note: McBride's Good Lord bird, whose feathers John Brown's son Frederick claims bring good luck and "understanding all your life," might be the ivory-billed woodpecker, although Kansas Territory might have been a bit northwest for one. People lucky enough to spot this large woodpecker reportedly cried, "Lord God!," and that gave it its nickname, the Lord God bird.

Hunting and overlogging drove this species near extinction in the late 1930s. For sixty years, it was feared extinct. In 2004, a sighting and sounds (characteristic tin-horn cries and double-knock pounding) were reported in the Big Woods of Arkansas, but extensive searching by ornithologists has produced no definitive evidence that the ivory-billed woodpecker still exists in America. That's very unlucky for us.