In Christopher Fowler's Peculiar Crimes Unit series, the PCU is the red-headed stepchild of London policing, despite the fact that its case clearance rate is stellar and its budget tiny. The PCU's unpopularity with the police and government establishment is largely due to its chief, Arthur Bryant. Bryant is an ancient, shambling man in shabby and soup-stained clothing who is fascinated by history, the occult and odd phenomena, but who lacks any people skills or ability to deal with the real world.

In Christopher Fowler's Peculiar Crimes Unit series, the PCU is the red-headed stepchild of London policing, despite the fact that its case clearance rate is stellar and its budget tiny. The PCU's unpopularity with the police and government establishment is largely due to its chief, Arthur Bryant. Bryant is an ancient, shambling man in shabby and soup-stained clothing who is fascinated by history, the occult and odd phenomena, but who lacks any people skills or ability to deal with the real world.

In Bryant's world, phones malfunction after being smothered by toffee melting in his pocket, important evidence is tainted or goes missing, and entire buildings may be accidentally destroyed. After losing track of his car countless times, his solution is to make a habit of parking it in places that make people really angry, since that means when he's searching for it, people will remember having seen it. His way of dealing with a potentially troublesome journalist is to pretend to show her an iron maiden torture device, lock her in it and stroll off, forgetting all about her.

Bryant's principal colleague and best friend is John May, who is as dapper as Bryant is disheveled, and spends much of his time smoothing over ruffled feathers after Bryant has unfortunately been allowed to speak to witnesses or superiors. Other members of the PCU staff register on the misfit scale, too, just at a much lower level than Bryant.

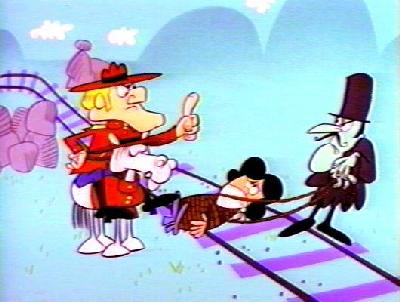

In the latest PCU book, Bryant & May and the Memory of Blood, the PCU is called in on a horrific case of the murder of a theater producer's infant son that is committed while the producer and his wife host a party to celebrate a new play with the production's cast and crew. What puts this crime within the PCU's remit is its bizarre and challenging circumstances. The boy was throttled and thrown out a sixth-floor window without anyone having witnessed any of the crime. The boy's nursery door was locked from the inside, and there is no evidence that will help identify the murderer. The crime scene is turned from puzzling to grotesque and eerie by the Punch puppet on the floor near the crib, and the fact that the impressions on the boy's neck match Punch's wooden hands.

While the rest of the PCU interview the party guests, construct timelines and analyze alibis, Arthur Bryant immerses himself in the arcana of puppetry, stage props and devices, and the history of the theater and of London buildings. He consults with carnies and Wiccans, and even a Victorian automaton of the seer Madame Blavatsky.

Bryant has a few other matters to distract him along the way. He and his housekeeper are being evicted from their longtime residence immediately––actually, it's only "immediately" because Bryant has spent months successfully avoiding paying any attention to the notices and his housekeeper's warnings. On another front, Bryant is dismayed when the appealing young woman who is helping him with his memoir is killed, and a CD of highly inflammatory and top-secret material culled from the memoir goes missing. To round off the distractions, hints begin to appear that someone in government is taking steps to discredit the PCU badly enough to force it to disband.

Bryant is convinced that a psychological drama is being played out by the staging of the murder and the use of the Punch puppet. The killer is trying to send a message. But what is the message, and for whom is it intended? Bryant's conviction grows as other guests at the party are murdered; their deaths also bizarre and apparently staged with reference to the Punch and Judy plays. As time goes by with no solution in sight, Bryant risks it all on one throw of the dice. He gathers the suspects and vows to his team that he will have his murderer by midnight or retire.

Bryant is convinced that a psychological drama is being played out by the staging of the murder and the use of the Punch puppet. The killer is trying to send a message. But what is the message, and for whom is it intended? Bryant's conviction grows as other guests at the party are murdered; their deaths also bizarre and apparently staged with reference to the Punch and Judy plays. As time goes by with no solution in sight, Bryant risks it all on one throw of the dice. He gathers the suspects and vows to his team that he will have his murderer by midnight or retire.There is nobody like Christopher Fowler for combining dark, even horrifying, crime with comedy. Within seconds after wincing at a description of a crime scene, you may burst out laughing at one of Bryant's scathing observations.

Despite the contemporary setting and the (very occasional) use of modern forensic tools, PCU books harken back to classic mysteries, where a careful analysis of the clues and the suspects' movements––and the ability to spot red herrings and deceit––allow the reader to engage in the detection of the killer alongside the PCU team. Bryant & May and the Memory of Blood also provides the bonus of an entertaining education in the history of Grand Guignol plays and puppetry. I never had any particular interest in those subjects before, but I was fascinated. Now, that's the sign of a masterful writer.

This is the ninth book in the Peculiar Crimes Unit series, but if you haven't read the previous books, you'll be fine starting with this one. Bryant & May and the Invisible Code, the next book in the series, will be published in the UK by Doubleday in August. It's no mystery whether I'll buy it or wait for the US publication, which looks like it will be at least six months later.

* * * * *

A City of Broken Glass by Rebecca Cantrell

In Rebecca Cantrell's Hannah Vogel series, Hannah is a Berlin reporter in the 1930s who runs into trouble––a lot of trouble––with a variety of Nazi brownshirts and members of the regime, and ends up having to leave Germany for Switzerland and live under an alias. In this fourth book in the Hannah Vogel series, it's late 1938 and Hannah is on a reporting assignment to Poland from her Swiss newspaper. She's supposed to cover a local festival––not exactly hard-hitting stuff––and has brought her 13-year-old adopted son, Anton, along. Hannah drops her festival assignment when she learns that thousands of Jews of Polish heritage have been violently driven from Germany by the Nazis and are being held by Polish authorities in barns and factory buildings, with little food and no facilities.

| Gestapo officer |

It's a challenge to review this book in a way that will be helpful to potential readers, because this series has two very different potential audiences. One audience is readers who enjoy romantic mysteries, or at least mysteries with a strong focus on the protagonist's personal life and concerns. If you're in this category, it's likely you'll enjoy A City of Broken Glass. And, if you've enjoyed previous books in the Hannah Vogel series, this is the best since the first book, A Trace of Smoke.

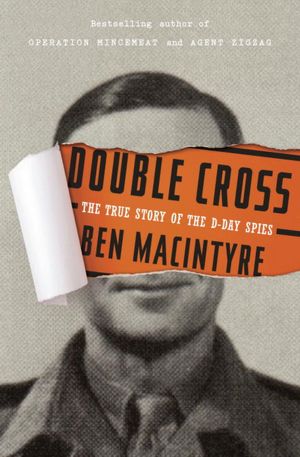

The second potential audience is readers who seek out mysteries, thrillers and espionage books dealing with the Nazi and World War II eras. This group may well be less than enthusiastic about the book. I'll tell you why, but first a little background.

|

| Herschel Grynszpan |

|

| Synagogue on fire on Kristallnacht |

The story between the two historical events that begin and end the book is the place where the two potential reader audiences may part ways. While Hannah investigates, she has plenty of time to devote to her troubled relationship with Lars, and learning what he has been doing in the two years since they parted. It's an interesting enough story, and their troubled romance is well presented. This will be satisfying to the first type of potential audience. For those who prefer a focus on the history, rather than the personal, though, the emphasis on the Hannah/Lars relationship may feel like unnecessary filler.

A City of Broken Glass will be published by Macmillan on July 17, 2012.

Note: I received a free review copy of A City of Broken Glass. Versions of these reviews appear on each book's Amazon product page under my Amazon user name.