Sure, it seems like the only international mysteries anybody has been able to talk about for the last couple of years are Nordic crime novels. That's the legacy of Stieg Larsson's books. But long before tattooed and pierced girls like Lisbeth Salander came along, biking around Stockholm, readers have loved novels set in France.

It's autumn now, the time when all good French citizens have returned from their long August vacations and are back to their workaday lives. It may be the best time for us to take a trip to France. The harvest is on, the days are growing shorter, and there is a crispness in the evening air that invites us to pour a warming glass of wine or a cognac.

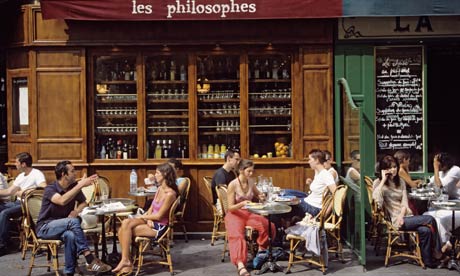

The thing about French mysteries—at least those written in English—is that they're almost inevitably "lifestyle" novels too. Not that that's a bad thing. In between finding dead bodies and chasing down bad guys, detectives sit at café tables with a pastis or go to a favorite bistro to dine on perfectly prepared oysters, paté terrines, tapenade, escargots, cassoulet, haricots, asparagus, coq au vin and unpasteurized cheeses, along with, of course, lovingly chosen wines. They walk down narrow streets in a Paris arrondissement steeped in history, or a market square in a sun-soaked village in Provence or the Dordogne.

British adman Peter Mayle is almost single-handedly responsible for the absolute crush of British and Americans visiting and wanting to live in Provence in the last 20 years. Mayle's

A Year In Provence was so filled with good food, wine and entertaining local color that he was able to make a living writing followups to the book. They include a few meringue-light caper-style mysteries:

Hotel Pastis,

Anything Considered,

The Vintage Caper and

Chasing Cézanne, and a novel with a slight mystery element,

A Good Year. The only substantive element in these books is the luxurious food and wine, but they are a pleasant way to pass some time and dream of a visit to France.

Not surprisingly, British travel writers have a propensity to want to live in France and to write about it. M. L. Longworth, a longtime travel writer, has just written her first mystery, called

Death at the Chateau Bremont, set in the city of Aix-en-Provence. This is the start of a new series featuring judicial investigator Antoine Verlaque and his former lover, law professor Marine Bonnet. I didn't find Longworth to be completely successful in her plotting or creating believable and compelling characters, but she did manage to convey a mouth-watering sense of place and has a promising writing style that makes me think I'll be trying her next book.

Fellow British travel writer Martin O'Brien writes a more gritty style of mystery, befitting his locale: the sun-soaked but sometimes seedy and dangerous port of Marseilles. His protagonist is Chief Inspector Daniel Jacquot, a former rugby player. The Jacquot series doesn't start out well–

Jacquot and the Waterman and

Jacquot and the Master are weakly plotted–but Jacquot is a strong character and when O'Brien moves his story into country village settings in

Jacquot and the Angel and to the Côte d'Azur in

Jacquot and the Fifteen, there is more depth to his storytelling. Truth be told, though, O'Brien never gets better in his plot resolutions, which leaves his stories in the second tier.

A better series choice would be Martin Walker's Bruno Courrèges series, set in the Périgord town of St. Denis. Bruno is a veteran of the war in the Balkans and is now happy to be in this backwater, living alone in a small cottage with his dog, Gitane, cooking for himself, simply but beautifully, and whiling away his evenings on his patio. But in the debut novel,

Bruno, Chief of Police, St. Denis is soon the scene of the brutal murder of one of its longtime residents, a man of Arab descent who'd been a hero in World War II. For me, this first book and its successor,

The Dark Vineyard, were pleasant visits to a charming village where everybody seems to be a gourmet cook and champion drinker. I haven't yet felt inspired to pick up the next two in the series,

Black Diamond and

The Crowded Grave, but next time I want to visit the Dordogne, I can imagine letting Martin Walker take me there.

What would a trip to France be without time spent in the City of Light? For over a decade, Cara Black has been escorting us all over Paris in the company of her protagonist, computer security consultant Aimée Leduc. There is plenty of gastronomic envy for the reader of these books, but you may also yearn for Aimée's vintage Chanel, agnès b and other couture clothing. Even better, each book takes us on an in-depth tour of a different neighborhood in Paris. It's the next-best thing to being there. If you haven't discovered these books yet, start with

Murder in the Marais, the first in the series and a finalist for an Anthony and a Macavity award.

All the books I've described so far were originally written in English, and clearly by authors reveling in the French lifestyle. Open your horizons to translated books and you'll see the world of the native French. It might not be as pretty as the world seen by the Anglo Francophile, but a mystery fan always wants to see the real thing.

A bad old joke: "What do the Chinese call Chinese food?" "Food." Reading a French mystery written by a French native, as opposed to an English or American native, is sort of like that. Where the Anglo rhapsodizes about his protagonist's morning espresso and a warm and oozing

pain au chocolat, the French writer's character just eats breakfast.

The best-known French mystery writer is, of course, Georges Simenon, whose protagonist is Inspector Maigret of the Paris police. Maigret doesn't wear designer clothes. He can invariably be found wearing a bowler hat and an overcoat and carrying a pipe. He works from a perpetually chilly office. The appeal of the Maigret books is in his style of detection. He is no Sherlock Holmes. He doesn't scrutinize physical evidence, have an encyclopedic knowledge of footprints or tobacco, or dazzle with his feats of deduction. Maigret is a patient observer of people, and his knowledge of people leads him to the truth.

Similarly, Fred Vargas's Commissaire Jean-Baptiste Adamsberg relies on his understanding of the human psyche to solve crimes. He is shy, introspective and often unfathomable. A bit of a lady killer, but we tend to see little evidence of that. He doesn't spend much time sitting in cafés or restaurants. In Vargas's most recently translated novel,

An Uncertain Place, Adamsberg's spare time is spent delivering kittens and getting chiropractic adjustments. Not much of a lifestyle book, then. When he and his team of detectives meet in a local bar, there is no loving description of vintages and bowls of olives. They just drink wine, period. Danglard, Adamsberg's second-in-command, drinks more than the rest, mostly from the bottle in his desk drawer. The only time I can remember Vargas waxing rhapsodic about food and drink is when Adamsberg pursues an investigation to Serbia.

Some French crime novels would have to be seen as

anti-lifestyle books. Jean-Patrick Manchette wrote 10 standalone crime novels, three of which have been translated into English:

Three to Kill,

Fatale and

The Prone Gunman. These books are violent, spare, detached and almost impossibly noir. You will not feel envious of the protagonists' lifestyles but, if you like noir, you should give his books a try. Two of his titles are even available in English in graphic-novel form, with

Three to Kill published as

West Coast Blues and

The Prone Gunman published as

Like a Sniper Lining Up His Shot.

The first title in Jean-Claude Izzo's Marseilles trilogy is

Total Chaos, which is a pulsing neon clue that this is no travelogue. The next two volumes,

Chourmo and

Solea, drive home the point. Izzo's work is called Mediterranean noir. Unlike traditional noir, a genre in which the mean streets are usually gray and rainy, in Mediterranean noir the sun blasts down in a brilliant platinum white, illuminating the brilliant blue of the sea and the reds, yellows and greens of the buildings and billboards. Izzo's protagonist, police detective Fabio Montale is, like Izzo himself was, the son of immigrant parents and part of the ethnic and racial melting pot of Marseilles. Also like Izzo, Montale believes in a

liberté, égalité et fraternité that he doesn't find much of in a racist, corrupt police department or in modern France as a whole, especially among the far-right supporters of the National Front, which was founded in Marseilles.

To the non-native author, France is like a lover. Sometimes the writer is in the first flush of infatuation and everything is transcendently wonderful. Sometimes it's a more mature love, with the writer aware of flaws but finding them charming or at least being willing to forgive them. To the native author, though, France is more like family; somebody the writer is indelibly attached to, somebody whose flaws are all too evident, somebody the author may even hate sometimes; but somebody the author is compelled to care about deeply, no matter what. For readers, being taken to either France is a trip to look forward to.

Other suggested French mysteries in translation:

Léo Malet was born in the far southern city of Montpellier, but he lived most of his life in and around Paris. He wrote 33 Nestor Burma novels, which are chock-full of colorful French slang. Nestor Burma has been called France's answer to Philip Marlowe and, in France, the novels featuring Burma have been adapted to film six times and into a seven-season television series. Malet intended to write a crime novel featuring each of Paris's 20 arrondissements and came tantalizingly close to his goal before his death. Malet's Nestor Burma crime novels available in English include:

120 Rue de la Gare,

Fog on the Tolbiac Bridge,

The Rats of Montsouris,

Mission to Marseilles,

Mayhem in the Marais,

Sunrise Behind the Louvre,

Dynamite Versus QED,

Death of a Marseilles Man and

The Tell-Tale Body on the Plaine Monceau. Unfortunately, these books are very hard to find.

Pierre Magnan has written nine books in his Provençal series featuring Commissaire Laviolette, two of which have been translated:

Death in the Truffle Wood and

The Messengers of Death. Another series features Séraphin Monge and takes place after World War I. Both titles in that series have been translated:

The Murdered House and

Beyond the Grave. Magnan also has a standalone novel translated as

Innocence.

Claude Izner is the

nom de plume of two Parisian bookseller sisters who write a series about another Parisian bookseller, Victor Legris, set in the late-19th-century

Belle Epoque. There are currently nine titles in the series, six of which have been translated:

Murder on the Eiffel Tower,

The Père-Lachaise Mystery,

The Montmartre Investigation,

The Assassin in the Marais,

The Predator of Batignolles and

Strangled in Paris.

Didier Daeninckx is a left-wing politician and leading French crime novelist. His novels often focus on France's poor record dealing with World War II Nazi collaborators and more contemporary bad behavior toward its Algerian residents and citizens. Novels available in English include

Murder in Memoriam and

A Very Profitable War.

Jean-François Parot writes the Nicolas Le Floch series, in which the protagonist is a Breton policeman working in Paris during the 18th century. Of the nine books in the series, five have been translated:

The Châtelet Apprentice,

The Man with the Lead Stomach,

The Phantom of the Rue Royale,

The Nicolas Le Floch Affair and

The Saint-Florentin Murders.

Á bientôt!

Just recently, I came across a set of new publications

from Penguin Press. Each month, beginning in Fall 2013, Penguin is re-releasing one of the 75 Maigret books, as chronicled by Simenon, and

the time was right to dive into these books.

Just recently, I came across a set of new publications

from Penguin Press. Each month, beginning in Fall 2013, Penguin is re-releasing one of the 75 Maigret books, as chronicled by Simenon, and

the time was right to dive into these books. "Ear unmarked rim, lobe large, max cross and dimension small

max, protuberant antitragus, vex edge lower fold, edge shape straight line." Even knowing a bit of ear anatomy didn't help me decipher this code.

"Ear unmarked rim, lobe large, max cross and dimension small

max, protuberant antitragus, vex edge lower fold, edge shape straight line." Even knowing a bit of ear anatomy didn't help me decipher this code..jpg) When Maigret meets the train on arrival in Paris, he is first

confronted with a dapper gentleman detraining who fits the description to a lobe, but he is

immediately called to see the corpse of a very similar gentleman, recently

killed and whose otic whorls and folds were eerily similar. But Maigret is sure

of his target, and the game of cat and mouse begins.

When Maigret meets the train on arrival in Paris, he is first

confronted with a dapper gentleman detraining who fits the description to a lobe, but he is

immediately called to see the corpse of a very similar gentleman, recently

killed and whose otic whorls and folds were eerily similar. But Maigret is sure

of his target, and the game of cat and mouse begins. Maigret uses his intuition to try to understand characters' motives and

what drove them to their destructive behaviors. He views most people with

compassion, tempered by a reality-based cynicism.

Maigret uses his intuition to try to understand characters' motives and

what drove them to their destructive behaviors. He views most people with

compassion, tempered by a reality-based cynicism.

Georges Simenon was born in 1903 in Belgium, but his life took him to France and the USA after World War II and, finally, to Switzerland. He wrote more than 200 books

under as many as 16 different pen names. What made him stand out was his

spare, direct prose that occasionally was poetic. He could evoke psychological

tension beautifully while, at the same time, keep a calm tenor as a counterpoint.

Georges Simenon was born in 1903 in Belgium, but his life took him to France and the USA after World War II and, finally, to Switzerland. He wrote more than 200 books

under as many as 16 different pen names. What made him stand out was his

spare, direct prose that occasionally was poetic. He could evoke psychological

tension beautifully while, at the same time, keep a calm tenor as a counterpoint.