It's hard to believe we're a week into 2015. I've already been swept into a maelstrom of deadlines, so I sat down tonight and quickly composed my list of favorite 2014 reads. I'll tell you about half of them today and the other half tomorrow. A different day or more reflection might have generated a different list; no matter, you can be sure I enjoyed the following books.

It's hard to believe we're a week into 2015. I've already been swept into a maelstrom of deadlines, so I sat down tonight and quickly composed my list of favorite 2014 reads. I'll tell you about half of them today and the other half tomorrow. A different day or more reflection might have generated a different list; no matter, you can be sure I enjoyed the following books. I love novels set in boarding houses, such as Muriel Spark's A Far Cry from Kensington. In places where unrelated adults are forced to live close together, eccentricities and resentments bloom like mold on old wallpaper. Sometimes escaping a fellow boarder is nearly impossible, and if you're British, there's the stiff upper lip to maintain and the manners demanded by civilization to remember. Of course, it's one thing to be irritated beyond all reason or to be bored to death––and another to actually be done to death. For example, Mrs. Bunting lies awake at night straining to hear whether her secretive upstairs boarder will leave the house in Marie Belloc Lowndes's The Lodger, made into a silent movie by Alfred Hitchcock. The lodger is obviously a gentleman despite his shabbiness, but could he be the serial killer terrorizing Victorian London? He's so odd, but his rent comes in so handy!

I love novels set in boarding houses, such as Muriel Spark's A Far Cry from Kensington. In places where unrelated adults are forced to live close together, eccentricities and resentments bloom like mold on old wallpaper. Sometimes escaping a fellow boarder is nearly impossible, and if you're British, there's the stiff upper lip to maintain and the manners demanded by civilization to remember. Of course, it's one thing to be irritated beyond all reason or to be bored to death––and another to actually be done to death. For example, Mrs. Bunting lies awake at night straining to hear whether her secretive upstairs boarder will leave the house in Marie Belloc Lowndes's The Lodger, made into a silent movie by Alfred Hitchcock. The lodger is obviously a gentleman despite his shabbiness, but could he be the serial killer terrorizing Victorian London? He's so odd, but his rent comes in so handy!There's an excess of dark secrets among the six tenants and the unsavory landlord of the seedy bed-sit at 23 Beulah Grove. In Alex Marwood's The Killer Next Door (Penguin, 2014), an incident one stifling London summer night unites the six tenants, who normally are extremely careful to mind their own business. What they don't know––but, we do––is there's a grisly reason for the bed-sit's bad drains. I stayed up much too late reading this weirdly chilling book, chock full of great characters and settings and laced with dark humor. It's perfect tension-filled suspense for a night you're looking to be creeped out.

After that book, I was casting about, looking for another boarding house setting, when I came across the name of Patrick Hamilton, an English writer who lived a hard life and died too young. In Hamilton's Hangover Square, a deteriorating George Harvey Bone resolves to win or kill conniving small-bit actress Netta Longdon in World War II-era London. It's a wonderful, memorable read, so I was thrilled to find a book by Hamilton I hadn't read, The Slaves of Solitude (originally published 1947; NYRB Classics, 2007). It's late 1943, and we move from the larger setting of the World War against fascism to the smaller war set in a suburban London boarding house, where the genteel Miss Roach, and others, have taken refuge from the London Blitz. It's impossible not to identify with this decent woman as she suffers through dinners with the bullying and pompous Mr. Thwaits, a villain worthy of Dickens, and takes tea with a brash American lieutenant. It's a lovely read, especially when accompanied by endless cups of tea and cookies you can choke on when you laugh at the superb dialog.

After that book, I was casting about, looking for another boarding house setting, when I came across the name of Patrick Hamilton, an English writer who lived a hard life and died too young. In Hamilton's Hangover Square, a deteriorating George Harvey Bone resolves to win or kill conniving small-bit actress Netta Longdon in World War II-era London. It's a wonderful, memorable read, so I was thrilled to find a book by Hamilton I hadn't read, The Slaves of Solitude (originally published 1947; NYRB Classics, 2007). It's late 1943, and we move from the larger setting of the World War against fascism to the smaller war set in a suburban London boarding house, where the genteel Miss Roach, and others, have taken refuge from the London Blitz. It's impossible not to identify with this decent woman as she suffers through dinners with the bullying and pompous Mr. Thwaits, a villain worthy of Dickens, and takes tea with a brash American lieutenant. It's a lovely read, especially when accompanied by endless cups of tea and cookies you can choke on when you laugh at the superb dialog.A boarding house or city under siege setting; themes of identity, memory, justice or redemption; crime fiction set in foreign places; satire; dystopian fiction; experimental fiction.... I have so many reading joneses I can barely begin to list them. I picked up Jesse Ball's Silence Once Begun (Pantheon, 2014) because I wondered what narrator/character Jesse Ball would discover during his investigation of the Narito Disappearances case in 1970s Japan. Eight people disappeared from villages in Osaka Prefecture, with only a playing card posted on their door to provide a common clue. From the opening pages, the reader knows thread salesman Oda Sotatsu isn't guilty of the crime, yet he confesses and then stands mute thereafter. Ball is a poet, and his book, the majority of which is in interview form, is a lyrical, disturbing, and fascinating exercise in how one goes about learning the truth. I'm still mulling over Ball's observations about the nature of justice and obsession.

There are never enough quiet nights when you get to select what you feel like eating or drinking and pair it with a book you feel like reading. This winter, a good accompaniment to hot coffee and a thick slice of gingerbread is The Devil in the Marshalsea, historical fiction by Antonia Hodgson (Mariner, 2014). If you're working on your New Year's resolutions, even better. Trust me, you'll be motivated to improve yourself after watching Tom Hawkins go to pot in 1727. He lands in Marshalsea Gaol, an infamous London debtors' prison where prisoners are divided––according to their ability to pay for food, drink, and protection––into the horrible Master's side and the infinitely more horrible Common side. (I need to check my Dante's Inferno for the corresponding circles of hell.) Tom may earn a get-out-of-jail-free card if he discovers who murdered his recent cellmate, Captain Roberts. Of course, Tom's culprit will have to suit Sir Philip Meadows, Knight Marshal of the Marshalsea. Hodgson's first novel is atmospheric and features believable characters. I'm pleased it's the first in a proposed series.

I was on the train, trying so hard to be quiet reading Lenny Kleinfeld's Some Dead Genius (Niaux-Noir Books, 2014), laughs were coming out my nose. It's Kleinfeld's second comic hardboiled book about Chicago homicide detectives Mark Bergman and John Dunegan (see Read Me Deadly's review of the first, Shooters & Chasers, here). Mark and Doonie investigate a bizarre series of murders set in Chicago's art world (great observations on the valuation and marketing of art), and it can be read as a standalone. As the reader, you're clued in to the bad guys' scheme and watch the cops play catch up, but the twisting plot and fast pace keep you only a bit ahead of the cops. Kleinfeld's writing is original: hip, vivid, and playful. The closest I can come to describing its flavor is to say it's like reading a seriously amped-up Elmore Leonard with an "adults' eyes-only" rating for profanity and sex. Despite the X-rated language and all the characters' cynicism, the cops are very nice guys. I like that a lot.

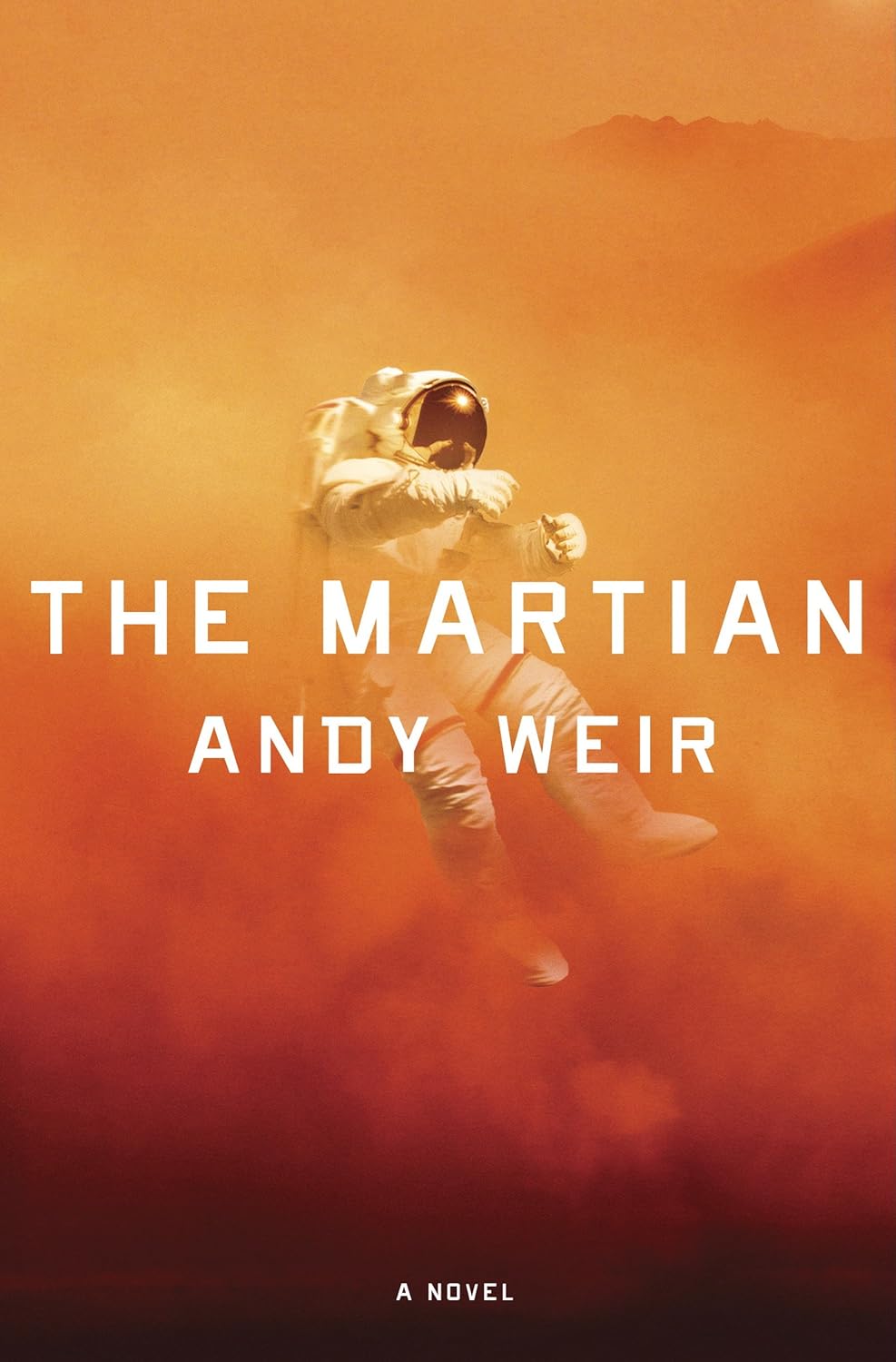

Last March when I reviewed Andy Weir's The Martian (Crown, 2014) (see review here), I predicted it would be one of my favorite books in 2014. And it is. The book begins when American astronaut Mark Watney is erroneously presumed dead by his Ares 3 crewmates and abandoned alone on Mars without any ability to communicate––or leave. Mark, who has a great sense of black humor, is determined to survive until the next manned mission to Mars. Unfortunately, that's scheduled for four years from now, and the food, water, and air will run out long before that. Mark is a botanist/mechanical engineer/Mr. Fix-It, and we read journal entries in which he describes a goal (say, creating water), how he means to do it, what went wrong, and how he'll fix it. His scientific explanations are clear, and his jerry-rigging is fascinating. After a few months go by, satellite pictures convince NASA Mark is still alive. Then, the loneliest man in the universe gets a little less lonely, and his goals change. It's hard to beat this book for its combination of inspiring, entertaining, and interesting.

I don't speak Chinese, and I hadn't read any Chinese science fiction before Cixin Liu's The Three-Body Problem (translated from the Chinese by Ken Liu; Tor, 2014). Cixin Liu is an engineer, and his book is hugely popular in China. Ken Liu's smooth translation maintains the original's Chinese flavor and adds some helpful explanatory footnotes at the bottom of the appropriate page. It's a two-threaded story featuring two scientists: Ye Wenjie becomes an engineer on a 1970s covert military project that seeks to establish contact with extraterrestrials after she loses her physicist father during the Cultural Revolution; Wang Miao, a modern-day nanotechnologist, begins to play a mysterious video game set on another planet called "The Three-Body Problem" after he is asked to help a police investigation into a series of scientists' suicides. These threads eventually connect in a very satisfying way.

The Three-Body Problem is heavy on the science and tech; however, the scientist-characters drive the plot, and Liu is interested in big questions about the human experience. I don't think physics classes or previous knowledge about the Cultural Revolution are necessary to enjoy this book, but they definitely enhanced my enjoyment. Liu's slowly emerging story is mesmerizing. The second book in the Three Body trilogy, The Dark Forest, will be published by Tor on July 7, 2015, and I can't wait to read it.

There are few ways to describe Celeste Ng's exquisite first novel, Everything I Never Told You (Penguin, 2014), that don't include the word "sad." The first sentences are heartbreaking: "Lydia is dead. But they don’t know this yet...." And that's not the only thing "they" don't know about Lydia. Lydia is the middle and favorite child of Marilyn and James Lee. The Lees moved to a small town in 1970s Ohio, where James, a Chinese-American whose parents immigrated to this country, teaches at the local college.

Both parents are bruised people who see Lydia as a vehicle to fulfill their dreams: Marilyn wants her to be the doctor she herself had hoped to become, instead of a housewife; James's desire is for Lydia to be popular at school. When Lydia's body is found in a local lake, James and Marilyn fall to pieces. Nathan, their oldest child and bound for Harvard, thinks Jack, a young James Dean type, might have something to do with it, while Hannah, barely registering in the family as the youngest, has another idea. This book takes a sensitive look at the hurts we suffer when we fail to fit in or measure up to expectations. It's also a terrific examination of magical thinking, family dynamics, and human resiliency and must be read to the unexpected end.

I'll be back tomorrow to tell you about my other 2014 favorites.

|

| I'm fantasizing about reading in the snow. Our high temperature today was 81. |