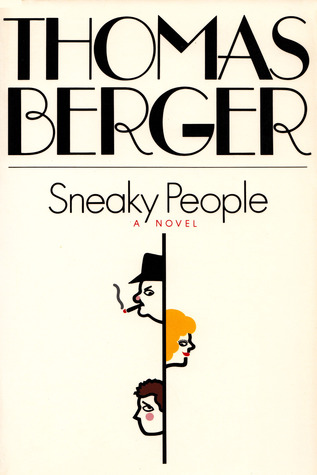

Like Conan Doyle with Sherlock Holmes, Walter Mosley killed off his protagonist in 2007's Blonde Faith. Whether the author just needed a vacation from his most popular detective, or had really intended to drop him forever, he was persuaded to relent. Little Green was published in 2013, and Rose Gold, the latest in the series, was released yesterday by Doubleday. I was fortunate to get a pre-release copy for review, and am very glad the author decided to resurrect the series; he has lost none of his touch.

Easy has his hands full in this story, set not too long after the first Watts riots in 1965, that turbulent period of Vietnam veterans and protesters, free love, black militarism, and hippies. It was a time when everyone had passionate opinions and society seethed with sit-ins and riots. Easy, a black decorated World War II veteran, usually tries to keep a low profile; the racial equality promised by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 hadn't yet had much effect on the lives of blacks in Los Angeles.

For a change, the Los Angeles police acknowledge needing Easy's help, and are prepared to pay for it. Roger Frisk, Special Assistant to the Chief of Police, approaches Easy, who is in the midst of moving house, and asks him to find Rosemary Goldsmith, daughter of a millionaire arms dealer. Rosemary has disappeared from her college dorm room, likely in the company of a militant young black boxer named Bob Mantle, who is calling himself Uhuru Nolicé. Mantle is wanted for the shooting of three police officers during the course of a robbery. Whether Rosemary went with him willingly or was kidnapped is a matter of conjecture. Frisk wants Easy to find Mantle and recover the girl if possible, but under no circumstances to contact her family.

For a change, the Los Angeles police acknowledge needing Easy's help, and are prepared to pay for it. Roger Frisk, Special Assistant to the Chief of Police, approaches Easy, who is in the midst of moving house, and asks him to find Rosemary Goldsmith, daughter of a millionaire arms dealer. Rosemary has disappeared from her college dorm room, likely in the company of a militant young black boxer named Bob Mantle, who is calling himself Uhuru Nolicé. Mantle is wanted for the shooting of three police officers during the course of a robbery. Whether Rosemary went with him willingly or was kidnapped is a matter of conjecture. Frisk wants Easy to find Mantle and recover the girl if possible, but under no circumstances to contact her family.But the L.A. police are not the only people interested in finding Rose. First the FBI shows up and tells Easy to drop the case, but to report any results from inquiries he has made to them and not to the L.A. police. When two State Department officials come by to say that he is interfering with national security and tell him to stay out of the case, Easy starts a slow burn. Despite his instructions to the contrary, he visits the girl's father. Foster Goldsmith will neither confirm nor deny that his daughter has been kidnapped. He tells Easy, "I taught Rose to make her own bed when she was six years old. I told her that when a man or woman makes their own bed they sleep in it too." Whew, tough love in these circumstances!

One of the most charming things about this series is the network of friends that Easy has managed to build. Rich or poor, on either side of the law, many people have reason to remember him kindly. Part of the reason is that he is willing to do favors for others. Melvin Suggs, Easy's informal contact in the police department, has been suspended. Melvin had arrested a woman for passing counterfeit money, but then fell in love with her. Their affair may cost him his job, even though Mary has since left him. In exchange for information, Mel wants Easy to find Mary, regardless of the consequences.

One of the most charming things about this series is the network of friends that Easy has managed to build. Rich or poor, on either side of the law, many people have reason to remember him kindly. Part of the reason is that he is willing to do favors for others. Melvin Suggs, Easy's informal contact in the police department, has been suspended. Melvin had arrested a woman for passing counterfeit money, but then fell in love with her. Their affair may cost him his job, even though Mary has since left him. In exchange for information, Mel wants Easy to find Mary, regardless of the consequences. By the time a ransom has been demanded––with one of Rosemary's fingers as earnest––Easy has begun to suspect that Bob Mantle, her apparent kidnapper, is being made a scapegoat by a number of parties. Rosemary is a wild child with a troubled past, who would love to publicly embarrass her father. When a robbery at a liquor store occurs, the tape shows Rosemary, holding a gun, robbing the clerk, while Bob timidly guards the door.

The story is loosely based on the Patty Hearst case of the same era. Patty, a daughter of publishing mogul Randolph Hearst, was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army, a self-styled left-wing revolutionary group, which she later joined. She was convicted of bank robbery and served time in prison, but is still thought by many to have been a victim of Stockholm Syndrome, in which the kidnapped bond closely with their captors.

The story is loosely based on the Patty Hearst case of the same era. Patty, a daughter of publishing mogul Randolph Hearst, was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army, a self-styled left-wing revolutionary group, which she later joined. She was convicted of bank robbery and served time in prison, but is still thought by many to have been a victim of Stockholm Syndrome, in which the kidnapped bond closely with their captors. In this series Mosley––with some humor and without lecturing or excessive bitterness––presents clearly the difficulty of living in America as a second-class citizen. In each of the Easy Rawlins books, my blood pressure spikes several times at the casual dismissiveness or outright cruelty of bigotry. They are not the most comfortable reads for an empathetic person, but the perspective always gives me something to think about. Mosley's plots are complicated, but tightly woven. His characters are vivid, and after several books I feel that I know them. For those reading Easy Rawlins for the first time, this is not the best place to start; each book in the series builds on the network of friends and obligations that Easy established in earlier books. For those of us who remember those times, Rose Gold is tightly-woven, bittersweet reminder of a turbulent and exhilarating era.

Note: I received a free copy of Rose Gold for review.