Crooked Heart is the story of Noel Bostock and Vee Sedge, a couple of misfits in England during World War II. Noel is a 10-year-old orphan boy, living with his eccentric godmother, Mattie, in her rambling old house near Hampstead Heath. Mattie was a suffragette in the '20s and has a disdain for anything conventional, including the evacuation of children at the beginning of the war, keeping a house tidy, finding a new school for Noel when his old one closes, or listening to the local ARP Warden's lectures on air raid precautions.

Mattie decides to educate Noel herself, going on nature field trips to the Heath and setting him essays on subjects like "Would You Rather Be Blind or Deaf?," What is Freedom?" and "Should People Keep Pets?." Noel is happy not to have to go to school with other children, since his experience is that they are usually stupid and like to bully him for his nerdiness. When Noel and Mattie are not in session in their home school, Noel reads detective stories and Mattie sings old protest songs.

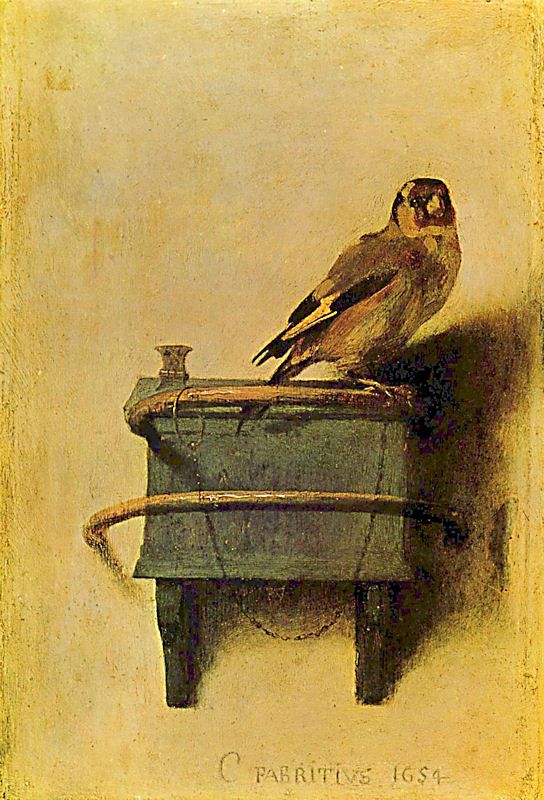

Mattie's eccentricity becomes more marked as she falls victim to dementia. At first, it can be amusing, like when she can't remember the last name of the architect of St. Paul's Cathedral, though she knows it's a bird's name, like Owl or Ostrich. Noel reminds her that it's Sir Christopher Wren, and she thanks him, but responds "I can't help thinking 'Sir Christopher Ostrich' has a tremendous ring to it." Far too soon, the sad day comes when Noel must be evacuated from London.

In St. Alban's, an odd boy like Noel doesn't find any quick takers, but the promise of government subsidy eventually persuades Vee Sedge to take him in. Vee is middle-aged, the sole support of her dotty mother, who spends her days writing letters to Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and her lump of a son, Donald, who uses his heart murmur as an excuse for utter sloth.

Vee is barely scraping by, cleaning houses and doing other odd jobs.The war gives her a chance to make some much-needed money on the fiddle, like so many others. Vee's particular scam is to collect for fake charities. The problem is, she's just not very good at it; too nervous and bad at keeping her stories believable and consistent. Noel, the world's youngest management consultant and business partner, turns Vee's business into a far more successful entrepreneurial effort.

|

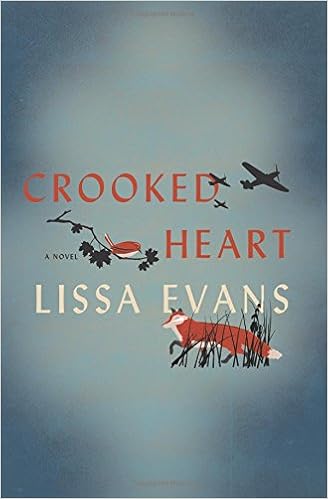

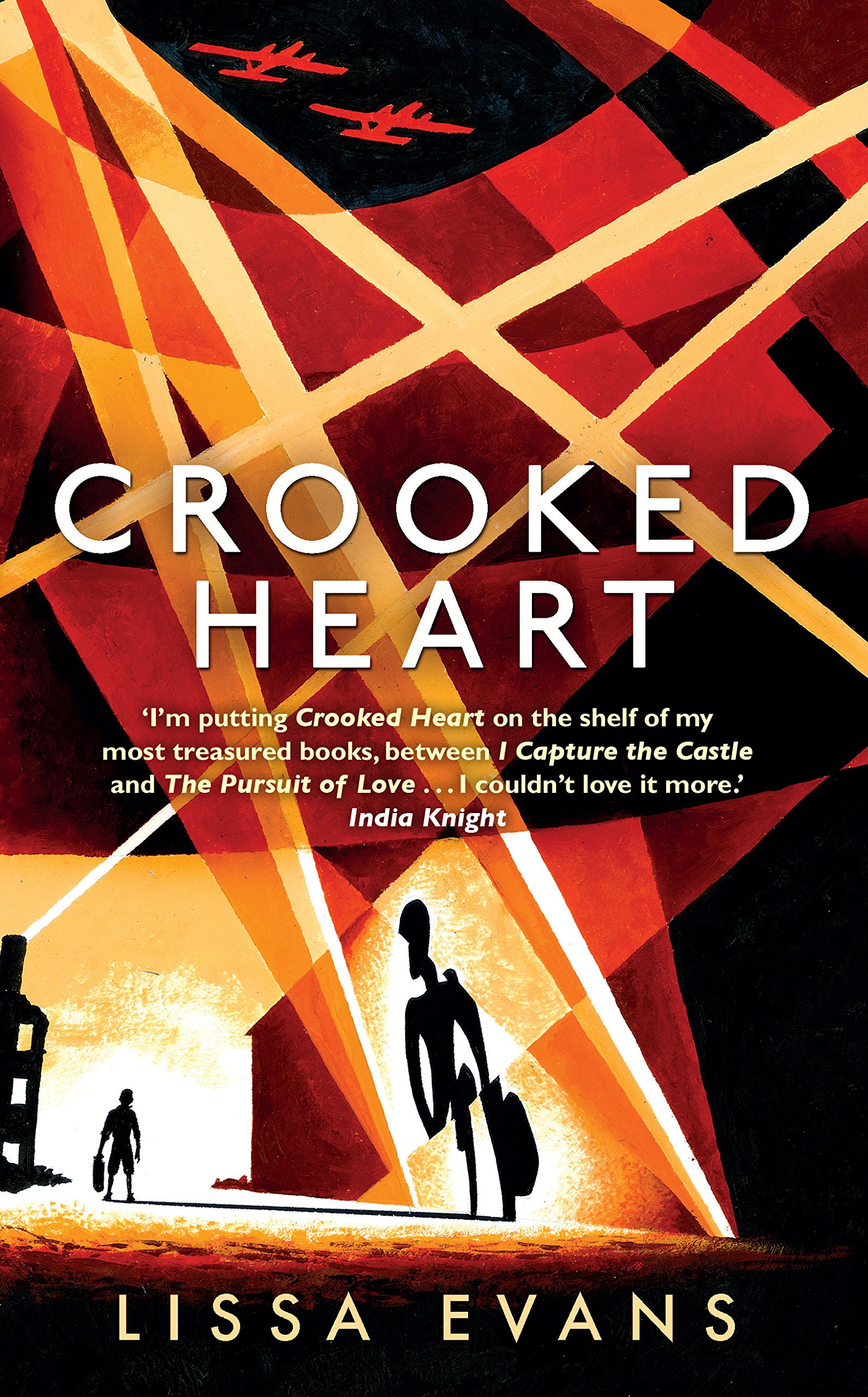

| The US cover (top) is fine, but isn't the UK cover striking? |

But don't forget, this is an English novel, which means that just as there was very little sugar allowed by a wartime ration book, this is a story that is never overly sweet. It reminded me a bit of John Boorman's wonderful semi-autobiographical memoir of his boyhood in wartime England, the movie Hope & Glory.