Recent reading has me contemplating human nature and destiny. Before we get to the actual books that inspired this thinking, we could warm up our minds by looking at Shakespeare for Cassius's ideas about being our own masters versus the fault in our stars or King Henry IV's desire to peek at the book of fate; however, it's Monday, and our heads are already spinning without the stimulus of the Bard. Let's ask instead why the chicken crossed the road. And no, we can't say it's simply to get to the other side.

Recent reading has me contemplating human nature and destiny. Before we get to the actual books that inspired this thinking, we could warm up our minds by looking at Shakespeare for Cassius's ideas about being our own masters versus the fault in our stars or King Henry IV's desire to peek at the book of fate; however, it's Monday, and our heads are already spinning without the stimulus of the Bard. Let's ask instead why the chicken crossed the road. And no, we can't say it's simply to get to the other side.I love the answers Harvard's David Morin attributes to physicists such as Einstein ("The chicken did not cross the road. The road passed beneath the chicken.") and Schrodinger ("The chicken doesn’t cross the road. Rather, it exists simultaneously on both sides . . . just don’t peek."), but those answers are observational. They don't really examine the nature of the chicken and the road or the roles played by the chicken's motivations and choices, as well as fate, in its crossing.

|

| Sorry, Dr. Martin Luther King, but we're grilling these birds. |

Let's interpolate from the philosophers' ideas about a chicken's behavior in crossing the road to the behavior of the characters in books I've recently read.

|

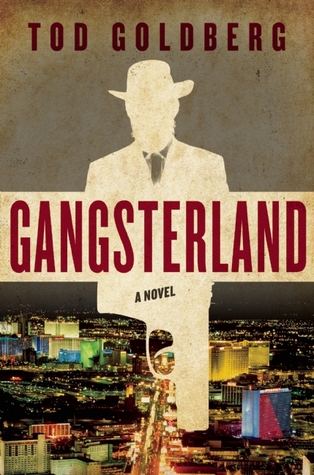

| If David Bowie can look like a Polish chicken, Sal Cupertine can pass for Rabbi David Cohen. |

That sort of thing doesn't just slip unnoticed into the night. Jeff is placed on administrative leave. In the meantime, the Mob hustles Sal out of town for a series of plastic surgeries and quiet time for studying the Talmud (not difficult for Sal, who is known as "the Rain Man" for his memory), and then resurrects him as Rabbi David Cohen in Las Vegas. Las Vegas isn't what it used to be for organized crime, what with the corporatization of gambling and casinos, but there are still ways for connected guys to muscle in on the action in secondary markets, including construction, strip clubs, and drugs not handled by the Bloods and Crips. Believe it or not, there's even a place for a man like Sal at Temple Beth Israel, whose growing complex houses two rabbis, a mortuary, a cemetery, and a private school.

That sort of thing doesn't just slip unnoticed into the night. Jeff is placed on administrative leave. In the meantime, the Mob hustles Sal out of town for a series of plastic surgeries and quiet time for studying the Talmud (not difficult for Sal, who is known as "the Rain Man" for his memory), and then resurrects him as Rabbi David Cohen in Las Vegas. Las Vegas isn't what it used to be for organized crime, what with the corporatization of gambling and casinos, but there are still ways for connected guys to muscle in on the action in secondary markets, including construction, strip clubs, and drugs not handled by the Bloods and Crips. Believe it or not, there's even a place for a man like Sal at Temple Beth Israel, whose growing complex houses two rabbis, a mortuary, a cemetery, and a private school. |

| Tod Goldberg |

Currently, he's stuck in Las Vegas, forbidden to call his wife and unable to look in the mirror without surprise, but he has plenty of time to think about who's pulling whose strings, how he got where he is now, and what the Talmud says about starting over. The Temple's members love Sal as David. Does this change him? Does the demonization of Jeff Hopper in the press and the lack of support from his former FBI superiors stop him on his quest to find Sal Cupertine? Everyone in Gangsterland does what he or she has gotta do, or at least what they think they gotta do. Sartre, anyone? They all gotta cross that road.

|

| The Long Island Red symbolizes Achilles and his lover, Briseis, both of whom have flame-colored hair. |

We can't discuss the humans of Greek mythology without mentioning the gods, who like to venture down from Olympus and meddle in mortals' lives. Favored mortals sometimes become pawns in the gods' Machiavellian games, although as famous Greek warrior and half-god Achilles says, "The gods and goddesses can do many things as suits them, but they cannot alter fate. Goddesses must bow before fate no matter how much it grieves them." Achilles doesn't have far to look for an example: his mother, the sea nymph Thetis, didn't succeed at burning away all his mortality when he was a baby. They are both aware of the prophecy that he will not return from the Trojan War.

As we know from Homer's Iliad, the Trojan War was prompted by Aphrodite's promise that Trojan prince Paris could have the world's most beautiful woman. Thus, Paris abducted––or eloped with––Queen Helen of Sparta. Her husband's brother, King Agamemnon of Mycenae, led forces gathered from around the Hellenic world to lay siege to Troy and get her back. While the Greeks are waiting, Agamemnon orders Achilles to pillage some nearby cities for treasure and women captives. While sacking Lyrnessos, Achilles meets Briseis, a beautiful young healing priestess and wife of Prince Mynes, when she tries to kill him. Of course, they fall in love.

As we know from Homer's Iliad, the Trojan War was prompted by Aphrodite's promise that Trojan prince Paris could have the world's most beautiful woman. Thus, Paris abducted––or eloped with––Queen Helen of Sparta. Her husband's brother, King Agamemnon of Mycenae, led forces gathered from around the Hellenic world to lay siege to Troy and get her back. While the Greeks are waiting, Agamemnon orders Achilles to pillage some nearby cities for treasure and women captives. While sacking Lyrnessos, Achilles meets Briseis, a beautiful young healing priestess and wife of Prince Mynes, when she tries to kill him. Of course, they fall in love. |

| Judith Starkston |

Oh, and so why would Starkston's characters cross the road? For Achilles, I'll go with Emily Dickinson's reasoning for a chicken's crossing, "Because it could not stop for death." Through dying, Achilles achieves immortality in legends. As for the independent-minded Briseis, I think Captain James T. Kirk of the Starship Enterprise has her number: "To boldly go where no chicken has gone before."

Note: If you love chickens, as I do, you might be interested in Stephen Green-Armytage's Extraordinary Chickens, a book of gorgeous photographs of unusual chicken breeds from around the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment