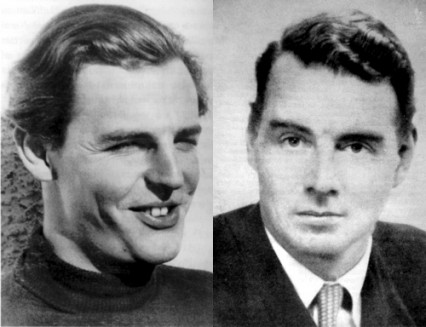

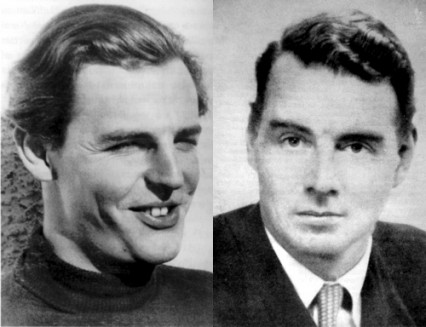

Young Philby

Young Philby by Robert Littell

Kim Philby, one of the most famous spies of all time, was a member of the so-called Cambridge Spy Ring. Donald Maclean, Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt and Philby all met while at Cambridge University and were recruited in the 1930s to become agents of the Soviets' NKVD security agency––which later became the KGB. As was common for Cambridge graduates, they gained important places in British government. Burges, Blunt and Philby joined the MI-5 and MI-6 intelligence agencies during World War II, and Maclean was in the Foreign Office.

|

| Maclean and Burgess |

Burgess and Maclean defected to the USSR suddenly in 1951, and Philby, who was then head of his agency's Soviet section and had been chief liaison with the CIA, was suspected of having tipped the pair off that they were about to be arrested. Though Philby was forced to resign, in large part because the CIA wouldn't collaborate with the British if Philby had stayed on, he wasn't arrested. He returned to his previous journalist career, where he stayed until 1963, when he disappeared from Beirut and reappeared as a defector in Moscow. There he stayed, until his death 25 years later.

|

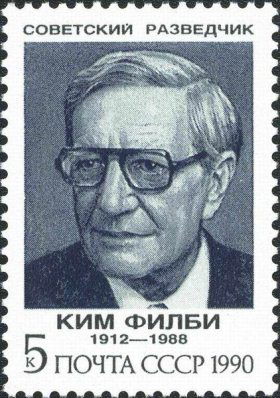

| Kim Philby |

More than the other members of the Cambridge Spy Ring, Philby has always been a figure who captured the imagination; possibly because he was so highly placed in the British government and was the top person in British intelligence responsible for combating Soviet spies. Some still believe Philby may not have been a double agent, but a

triple agent––in other words, ultimately still working for British intelligence, feeding disinformation to the Soviets, along with dispensable true information to make the disinformation easier to swallow. Characters based on Philby have appeared in many works of fiction, including John le Carré's classic,

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy.

|

| St. John Philby |

Young Philby is a mix of fact and fiction, taking what is known of Philby's doings after Cambridge and filling in the gaps with what author Littell imagines of Philby's life and how he came to participate in the "great game" of espionage. Littell cleverly does this by having each chapter narrated by a different character in Philby's life, including his various NKVD handlers; his first wife Litzi Friedman, who met him in Vienna in 1934, where both worked with the communists fighting the troops of right-wing Chancellor Dollfuss; Guy Burgess; and Evelyn Sinclair, tart-tongued daughter of and secretary to the chief of British intelligence. Contributions are also made by Philby's "sainted father," Harry St. John ("St. John," or "Sinjin") Bridger Philby, one of those amazing characters from Britain's colonial period who was seduced by Arab life.

Each narrator presents his or her own perspective on Philby, in a way that is reminiscent of the fable about the blind men and the elephant. (Each blind man touches a different part of the elephant and then uses what he has perceived to describe what an elephant is. None of the men has discerned the entire truth and each one's conclusion is wildly different from the next.) What was Philby then? A romantic who fought for the proletariat and against fascism in the streets of Vienna in the 1930s? A man who, having had his youthful fling, settled down to the conservatism of his class and upbringing? A consummately skilled player in the multi-level chess game of espionage?

|

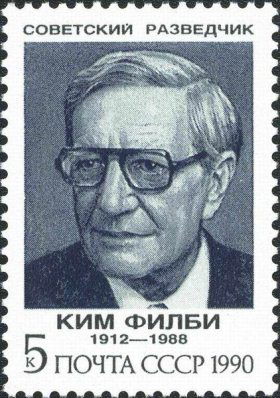

| Soviet stamp commemorating Philby |

Littell takes all his narrators' accounts of Philby and makes his own intriguing case for what Philby really was. Along the way, he leads us on a whirlwind tour of street fighting in Vienna, a journalist's beat during the Spanish Civil War, the gentlemen's-club atmosphere of British intelligence's Caxton House, and the depths of Moscow's Lubyanka Prison, where NKVD operatives were either interrogator or interrogated, depending on whether they had yet fallen victim to the deadly dialectic of Stalin's paranoid purges. Though I was riveted by the Philby story, every chapter made me want to know more about each narrator's life and times.

Though I'm an avid reader of Cold War espionage books––fiction and nonfiction––I haven't previously read any of Littell's books, which include

The Company: A Novel of the CIA,

The Sisters and

The Once and Future Spy. After reading

Young Philby, that now seems like a regrettable oversight––and one that I will remedy as soon as possible.

Young Philby was published on November 13, 2012 by Thomas Dunne Books, a division of St. Martin's Press.

Note: A version of this review may appear on Amazon and other sites under my user names there.

No comments:

Post a Comment