Syndrome E by Franck Thilliez,

Syndrome E by Franck Thilliez,translated by Mark Polizzotti

Quick. I say, "French," you say. . . . If the words "thriller" or "noir" don't readily come to mind, you've been sadly deprived. Let me tell you about a best-selling French thriller recently released in the United States by Viking, Syndrome E, by Franck Thilliez.

A supervisor once described 37-year-old Lucie Henebelle, a CID lieutenant in Lille, Belgium, as possessed––a good psychologist in the field, but sometimes out of control. And that's how her mother would describe her now. Lucie is supposed to be on vacation; however, one of her 8-year-old twin daughters is in the hospital, recovering from an illness. Instead of hanging around the sickroom, Lucie is investigating something frightening and bizarre: when her former lover, Ludovic Sénéchal, viewed a 1950s-era film purchased at an estate sale, he spontaneously became blind.

Now, we all know, no matter what the film's rating, this sort of thing doesn't happen with a Netflix rental. How could this occur? When Lucie watches Ludovic's mysterious 16 mm film, she's unsettled not only by its violent scenes, but its pleasant ones, too. Why would watching a little girl stroking a kitten disturb her? What's with the white circle in the frame's upper right-hand corner, the fog, and the large dark, flat areas on the sides and in the sky?

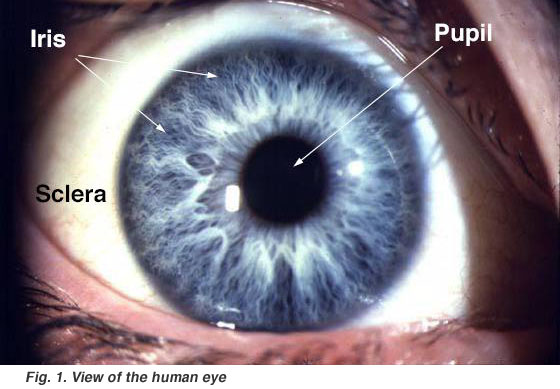

Now, we all know, no matter what the film's rating, this sort of thing doesn't happen with a Netflix rental. How could this occur? When Lucie watches Ludovic's mysterious 16 mm film, she's unsettled not only by its violent scenes, but its pleasant ones, too. Why would watching a little girl stroking a kitten disturb her? What's with the white circle in the frame's upper right-hand corner, the fog, and the large dark, flat areas on the sides and in the sky?There are two ways to see a film: through its plot and screenplay or through the medium itself. The eyes only supply the image to the brain; it's the brain that actually "sees" the film. It's possible for an image to be flashed by so quickly that the eyes don't have time to notice it, even though the brain has "seen" it. In the 1950s, knowledge of the brain and the impact of images on the mind was fairly primitive, but there was tremendous interest in this research. An American publicist––wouldn't you just know it––was the first to officially use a subliminal image in 1957. (Since then, there have been many reports of subliminal messages conveyed through mainstream media images, from advertising to political campaigning to attempts by the police to communicate with a criminal. Use of subliminal images is even the subject of a Columbo plot on TV in 1973.)

While Lucie's attention is focused on analyzing the film and tracing its history, Chief Inspector Franck Sharko (or "Shark") has been pulled out of his vacation to a crime scene outside of Rouen. Shark is a behavioral analyst in the Bureau of Violent Crimes in Nanterre, France. Theoretically, his job involves investigating unsolved violent crimes without leaving his desk. He cross-references information and establishes a psychological profile, using the computer and other informational tools to determine a killer's motives. The Rouen crime scene is a construction site, where five men have been unearthed. Their bodies are missing their teeth, hands, eyes, and the tops of their heads. Their brains have been removed. These are interesting corpses for behavioral analysis, but Shark is miserable. It's hot and muddy, and he hates mosquitos. Despite recent transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment of his schizophrenia, he's still troubled by hallucinations of Eugenie, a girl who taunts him about the deaths of his wife and daughter five years ago. Shark placates her with gifts of candied chestnuts and cocktail sauce and soothes himself with cold baths and the noise of a running model train engine.

While Lucie's attention is focused on analyzing the film and tracing its history, Chief Inspector Franck Sharko (or "Shark") has been pulled out of his vacation to a crime scene outside of Rouen. Shark is a behavioral analyst in the Bureau of Violent Crimes in Nanterre, France. Theoretically, his job involves investigating unsolved violent crimes without leaving his desk. He cross-references information and establishes a psychological profile, using the computer and other informational tools to determine a killer's motives. The Rouen crime scene is a construction site, where five men have been unearthed. Their bodies are missing their teeth, hands, eyes, and the tops of their heads. Their brains have been removed. These are interesting corpses for behavioral analysis, but Shark is miserable. It's hot and muddy, and he hates mosquitos. Despite recent transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment of his schizophrenia, he's still troubled by hallucinations of Eugenie, a girl who taunts him about the deaths of his wife and daughter five years ago. Shark placates her with gifts of candied chestnuts and cocktail sauce and soothes himself with cold baths and the noise of a running model train engine.Lucie's digging on behalf of her friend becomes a case for the police when Claude Poignet, the expert Lucie asked to "autopsy" the film, is found hanging by the neck; the noose is an old western film, Good Day for a Hanging. (I'll spare you the murderers' other creative uses of film at the scene.) As the Lille investigation proceeds, and more people are murdered, evidence links the film to the five men buried near Rouen. The Paris CID, the Lille team, and the Rouen cops combine their investigations. Lucie, whose loneliness hasn't been cured by her internet dating, is immediately attracted to Chief Inspector Sharko's competence. In one of the book's many references to film, she finds Shark shares the sadness of Léon, the contract killer in Luc Besson's The Professional, but also the same "incomprehensible sympathy that made you want to get to know him." Shark recognizes Lucie as driven as he is, and he warns her that "a cop's eyes should never shine, and hers gleamed way too much when she talked about her case." Such professional dedication takes a high personal toll.

Syndrome E is a suspenseful tale about heartbreaking inhumanity and early neuroresearch. It is a feast about and for our brains, featuring memorable settings (in France, Belgium, Egypt, and Canada) and the characters Lucie and Shark. It isn't a creepfest, in which terrible things happen simply to shock, but a worthwhile albeit upsetting look at a dark history involving governments, intelligence and military agencies, religious institutions, and scientific research. People should know about this history and understand its ramifications. In a few years, machines might allow the visualization of dreams. Scanners might project a defendant's memories in the courtroom. Where will neuroresearch go next? Thilliez's tale sent me on a binge of research, and his story's ending makes me wish for an English translation of the sequel, Gataca.

Note: There are disturbing images, particularly in the short Chapter 25. I don't often advocate skipping parts of a book, but for people who find cruelty to animals or children unbearable, really, it could be skimmed or skipped completely.

No comments:

Post a Comment