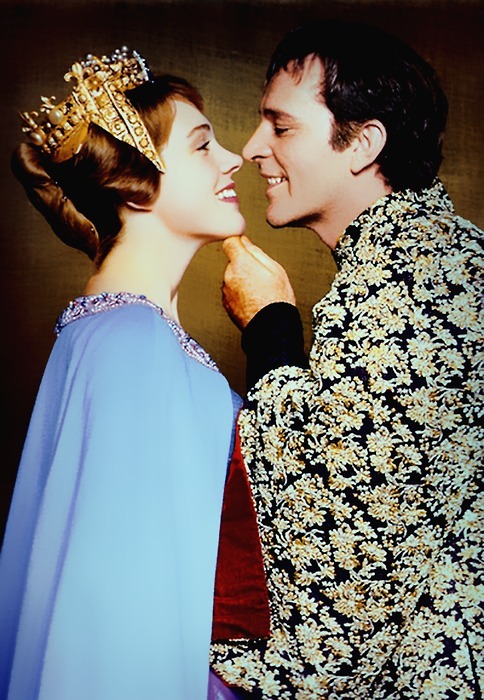

I had the good fortune in my teens to see a live performance of Lerner and Loewe's Camelot, with Julie Andrews and Richard Burton. They had a rather different take on this exuberant time of year than the sedate annual May processions to honor Mary, Queen of Heaven and mother of Jesus, that studded my childhood.

I had the good fortune in my teens to see a live performance of Lerner and Loewe's Camelot, with Julie Andrews and Richard Burton. They had a rather different take on this exuberant time of year than the sedate annual May processions to honor Mary, Queen of Heaven and mother of Jesus, that studded my childhood. "Tra la, it's May,sings the faithless Guinevere to her adoring Arthur. And we all know how that story came out! At the end, facing his certain death, Arthur laments:

The lusty month of May!

That lovely month when everyone goes

Blissfully astray."

"Ne'er let it be forgot, that once there was a spotMay is often like that––flowering everywhere with abandon, promising beauty that can't possibly be sustained, but glorious while it lasts. I welcome it joyfully every year and mourn its passing.

For one brief shining moment that was known as Camelot."

In many countries, the first of May is celebrated as International Workers' Day, or Labor Day. This holiday had its origin in a violent 1886 Chicago clash between police and workers demonstrating for shorter workdays. After several demonstrators were tried and hanged, socialists and labor activists throughout the world adopted the holiday in memory of the "martyrs." The United States was so embarrassed by the negative attention that it officially moved our Labor Day to the end of the month, opting instead to name May 1 "Loyalty Day." I must confess that I had never even heard of Loyalty Day.

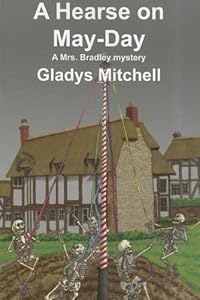

In Teutonic tradition, April 30––Walpurgis Night or Beltane––is the night when witches come out to play, dance, and make mischief. Weird and sometimes grisly rituals, often involving bonfires, still take place on this night throughout Europe, in preparation for the more staid and chaste May Day rituals to follow. In Gladys Mitchell's A Hearse on May-Day, young Fenella Lestrange, traveling on the last day of April to her cousin's house from which she will be married in a week, is starving. The next town on her route with a pub is over an hour away, so she consults her map and finds an out-of-the way town called Seven Wells. "At least I can get a ploughman's lunch there," she thinks, and off she goes over back roads rarely traveled. She finds the town eerily deserted for midday, although the early 16th-century half-timbered pub cryptically called More to Come serves her a decent lunch of chicken salad and sherry.

In Teutonic tradition, April 30––Walpurgis Night or Beltane––is the night when witches come out to play, dance, and make mischief. Weird and sometimes grisly rituals, often involving bonfires, still take place on this night throughout Europe, in preparation for the more staid and chaste May Day rituals to follow. In Gladys Mitchell's A Hearse on May-Day, young Fenella Lestrange, traveling on the last day of April to her cousin's house from which she will be married in a week, is starving. The next town on her route with a pub is over an hour away, so she consults her map and finds an out-of-the way town called Seven Wells. "At least I can get a ploughman's lunch there," she thinks, and off she goes over back roads rarely traveled. She finds the town eerily deserted for midday, although the early 16th-century half-timbered pub cryptically called More to Come serves her a decent lunch of chicken salad and sherry.When she tries to get on her way, her car, which had been checked by her local mechanic only the day before, refuses to start. The pub owner takes a look, but pronounces it a "garage job" and offers to drive her several miles to a town with a mechanic after his meal. The only phone in town is a public one outside the post office, but the scruffy young man who directs her there says, "That's out of order. Us done her yesterday." Fenella suspects that he and his friends may have "done" her car today, but has no choice but to wait for the innkeeper to finish his meal. When the mechanic finds that he needs to order a part, and there is no inn nearby, the innkeeper grudgingly offers Fenella a room at More to Come for the night.

Both Mr. Shurrock, the innkeeper, and his maid warn her repeatedly to stay in her room for the evening and to take no notice of outside events. "Mayering" activities in the village are apparently ancient and very secret. Strangers are unwelcome. Mrs. Shurrock shows her to a clean but spare room, gives her the key and shows her the staples and bar installed just that afternoon in her honor. "See that piece of wood? Well, fix that across before you get into bed. It's teak, and the door's solid oak. Nobody won't break that down, don't you fret," she reassures the now thoroughly unnerved Fenella.

Her courage and rationality restored by the rather meager dinner served in her room, Fenella slips out by the back stairs she had spotted earlier. She is quickly joined by a well-spoken but slightly mysterious young man, who urges her to return to her room. Uncertain whether his complimentary personal remarks are a pickup attempt, she returns to the inn, deciding to pick up a book she had spotted earlier in the lounge for bedtime reading. To her amazement, she interrupts a meeting of a dozen robed and cowled figures wearing masks of the characters of the zodiac. They question her sharply, and several seem disinclined to let her go, but she escapes from the room with her book. She is certain that Aries was the rude young man who put the phone out of order, and is sure she will recognize most of the others if she ever hears their voices again. Later she spies on the same group performing some arcane ritual in a cellar under the back stairwell. They emerge with a few bleached bones, which they place on a bier and proceed with them out of the building. At that point Fenella wisely decides to go to bed.

Her car is returned the next morning, and she is urged by the suddenly much friendlier innkeeper to take a look at the well-wishing at the seven sacred wells on her way out of town. The villagers, he says, will be torn between attending the Mayering and the funeral of Sir Bitten-Bittadon, the local squire, murdered last week. At the wells, Fenella meets the Green Man, whose voice she recognizes as the man who had followed her last night and persuaded her back to the safety of the inn.

Her car is returned the next morning, and she is urged by the suddenly much friendlier innkeeper to take a look at the well-wishing at the seven sacred wells on her way out of town. The villagers, he says, will be torn between attending the Mayering and the funeral of Sir Bitten-Bittadon, the local squire, murdered last week. At the wells, Fenella meets the Green Man, whose voice she recognizes as the man who had followed her last night and persuaded her back to the safety of the inn.Much to her relief, her cousins have invited her great aunt Dame Beatrice Bradley, polymath, psychiatrist, and frequent consultant to the Home Office, to stay with them. She listens to Fenella's tale and promptly calls in a consultant, a local schoolmaster knowledgeable in folklore. Fenella, with her acute ear for voices, again instantly recognizes the Green Man she met at the wells.

Dame Beatrice, who has a dual errand, is also in the area to help Scotland Yard solve the murder of the squire. They solve it, but only after three more murders are committed and a grave is robbed. The village of Seven Wells, in its Mayering Ceremonies, has not only made a virtue of an ancient and gruesome necessity, but enshrined it in bizarre rites that have continued long after the need has passed.

I had never heard of this author, who was a contemporary of Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers. She was nearly as prolific as Christie, writing over 60 books in the mystery genre, many with just a touch of the uncanny. If this story is indicative, her books are terrifically dense. It took a surprisingly long time to finish a book of less than 200 pages, although part of that may be due to the text, which in this Rue Morgue edition is small and difficult for my aging eyes to read. While A Hearse on May-Day was a little hectic and not really fair play––only one clue quite near the end nailed it for me––I enjoyed it enough to hunt up another in Ms. Mitchell's extensive oeuvre.

I had never heard of this author, who was a contemporary of Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers. She was nearly as prolific as Christie, writing over 60 books in the mystery genre, many with just a touch of the uncanny. If this story is indicative, her books are terrifically dense. It took a surprisingly long time to finish a book of less than 200 pages, although part of that may be due to the text, which in this Rue Morgue edition is small and difficult for my aging eyes to read. While A Hearse on May-Day was a little hectic and not really fair play––only one clue quite near the end nailed it for me––I enjoyed it enough to hunt up another in Ms. Mitchell's extensive oeuvre.Whatever flavor of May Day celebration you favor, don't forget to get outdoors and look around and breathe deeply. May only comes once a year and is over far too soon. And for those of us who can never have enough of Julie Andrews's astonishing voice, here is her welcome to this exuberant month.

This is a fascinating post. It brought a question up which the internet answered for me. I wondered where the use of 'mayday' as an SOS began.

ReplyDeleteAccording to an encyclopedia entry on SOS, "mayday" was used as a distress signal for aviators because it approximates the French term m’aider, meaning "come help me!" The term came into use between the years 1925-30.

MC, how interesting! I never knew why they used a holiday for a distress signal.

ReplyDeleteIf anyone is interested in reading Gladys Mitchell's long out of print books, Thomas and Mercer has purchased the electronic rights in the US, so we can count on more of her books to become available soon.

Awesome post! I mentioned it to my readers in my weekly newsletter. Please let me know if you would like a copy. Cheers,

ReplyDeleteKris

kris@kristenelisephd.com