Where There's Love, There's Hate by Adolfo Bioy Casares and Silvina Ocampo

Where There's Love, There's Hate by Adolfo Bioy Casares and Silvina OcampoIf travel is on your holiday agenda, the perfect take-along may be Where There's Love, There's Hate. Originally published in 1946, the novella was translated from Spanish into English by Suzanne Jill Levine and Jessica Ernst Powell and published in May, 2013 by Melville House.

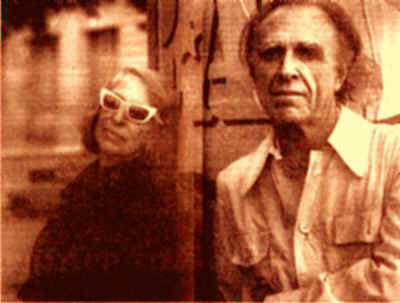

The novella's married authors, Casares and Ocampo, were famous Argentine writers and friends of Jorge Luis Borges. They've combined a sophisticated spoof of a detective story with a romantic satire. It's very vivid writing, jam-packed with eccentric characters, sly literary references and nods to Golden Age mystery writers, such as Michael Innes, Dorothy L. Sayers and Agatha Christie.

The story is narrated by Argentine physician Humberto Huberman, an arrogant pseudo-intellectual who looks like a pocket-sized Goethe and has a "perfect" appetite. In addition to treating patients, Huberman writes screenplays. He's working on an adaptation of Petronius and seeks solitude at his cousin Esteban's seaside hotel in Bosque del Mar, "the literati's paradise."

To reach the Central Hotel, one makes a dangerous journey over planks set across crab bogs and sinkholes that claimed the physician's horse. The hotel is like a foundered submarine, sinking in swirling sandstorms, and opening windows is impossible. The air inside is foul and full of buzzing flies that drown out dinner conversation. An elderly typist ("Muscarius"), armed with a flyswatter, hunts them when she isn't gently swaying her head in time to the dinner bell or foretelling trouble in the hours ahead. Also living at the hotel are Esteban's sister, Andrea, who cooks, and her 11-year-old son, Miguel, who's into exploring a grounded ship and embalming. Miguel's facial expression, which combines innocence and maturity, makes Huberman uneasy.

To reach the Central Hotel, one makes a dangerous journey over planks set across crab bogs and sinkholes that claimed the physician's horse. The hotel is like a foundered submarine, sinking in swirling sandstorms, and opening windows is impossible. The air inside is foul and full of buzzing flies that drown out dinner conversation. An elderly typist ("Muscarius"), armed with a flyswatter, hunts them when she isn't gently swaying her head in time to the dinner bell or foretelling trouble in the hours ahead. Also living at the hotel are Esteban's sister, Andrea, who cooks, and her 11-year-old son, Miguel, who's into exploring a grounded ship and embalming. Miguel's facial expression, which combines innocence and maturity, makes Huberman uneasy.Besides Huberman, guests include a young blonde woman named Emilia Gutiérrez, and her sister, Mary. Mary translates and edits detective novels and it's her habit to travel with everything she has ever translated. She works for a prestigious publishing house, but Huberman, who considers the detective novel unrealistic and childish, isn't impressed. Accompanying Emilia and Mary is Emilia's fiancé, Enrique Atuel, who reminds Huberman of a overly debonair tango crooner. Doctor Cornejo is middle-aged and knowledgeable about meteorology and the ocean. Pipe-smoking Doctor Manning plays game after game of solitaire.

From the guests' first day, when Mary comes close to drowning (although she denies it), scenes hint of the Grand Guignol. Emilia disappears before turning up at dinner with red and teary eyes. After dinner, she freezes when Mary asks her to play Liszt's Forgotten Waltz on the piano. The dogs howl and the wind, "as if grieving all the world's sorrow," whips the sand into a frenzy. By the next morning, someone is dead, a victim of suicide or murder.

The Central Hotel, in the middle of a sandstorm, was almost as closed to outsiders as Christie's island in And Then There Were None. Arriving to investigate are Commissioner Raimundo Aubry, who can't discuss crime without referencing Victor Hugo, and police physician Doctor Cecilio Montes, whose appearance is that of an escapee from a Russian novel. One might expect Huberman to be standoffish, since he says complicated crimes are the province of literature, while reality is more banal. But Huberman jumps to argue about the criminal using examples from literature. He becomes a detective, as does almost everyone––other than the corpse.

The Central Hotel, in the middle of a sandstorm, was almost as closed to outsiders as Christie's island in And Then There Were None. Arriving to investigate are Commissioner Raimundo Aubry, who can't discuss crime without referencing Victor Hugo, and police physician Doctor Cecilio Montes, whose appearance is that of an escapee from a Russian novel. One might expect Huberman to be standoffish, since he says complicated crimes are the province of literature, while reality is more banal. But Huberman jumps to argue about the criminal using examples from literature. He becomes a detective, as does almost everyone––other than the corpse.One after another, revelations are produced, accusations are made, suspects are cleared and Golden Age mystery conventions are skewered. After reality is confused with a book, it's a miracle that the case is solved.

No comments:

Post a Comment