How many of you have kicked your spouse under the holiday dinner table to warn him about dangerous conversational territory, only to be rewarded for your subtlety when he loudly demands, "Why are you kicking me under the table?"

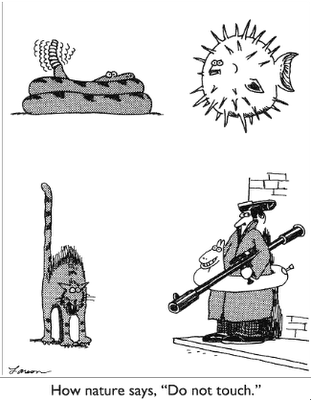

How many of you have kicked your spouse under the holiday dinner table to warn him about dangerous conversational territory, only to be rewarded for your subtlety when he loudly demands, "Why are you kicking me under the table?"I'm asking this question because I've been doing a lot of thinking about the assumptions involved in our communications, interpretations, and perceptions. It's easy to be wrong. Take the Gary Larson cartoon on the right. See the guy carrying the bazooka? Now, maybe Larson isn't kidding, and we can assume that man is a wacky, paranoid survivalist. In that case, it would be smart to avoid eye contact and skedaddle across the street. Then again, maybe Larson is joking. It could be Halloween, and that dude might be headed to a costume party. Or, perhaps he's some kids' beloved Uncle Bob, waiting on the corner to be picked up for a fun day of inner-tubing down the Green River, and his weapon is an awesome water gun for little Johnny or Susie. Yeah, that's the ticket. That's what I'll assume.

There are two books I've enjoyed recently because they explore themes of communication, interpretation, and perception. I'm going to tell you briefly about one of them today. I'll be back tomorrow to tell you about the other.

"I am a doctor," begins Marc Schlosser, in Herman Koch's deliciously dark Summer House with Swimming Pool (translated from the Dutch by Sam Garrett; Hogarth/Crown, June 2014). The cynical Schlosser isn't quite as good looking as George Clooney, but Schlosser tells us most people find him very charming. His liberal prescribing habits and the blind eye he turns on his patients' unhealthy overindulgences have created a practice popular with people in the creative and entertainment fields. (Oh man, we aren't as lucky as Schlosser's patients. He coddles them, but he doesn't spare us. His vivid observations about excessive eating and drinking's effects on the human body will make you padlock your fridge and abandon your liquor cabinet.)

"I am a doctor," begins Marc Schlosser, in Herman Koch's deliciously dark Summer House with Swimming Pool (translated from the Dutch by Sam Garrett; Hogarth/Crown, June 2014). The cynical Schlosser isn't quite as good looking as George Clooney, but Schlosser tells us most people find him very charming. His liberal prescribing habits and the blind eye he turns on his patients' unhealthy overindulgences have created a practice popular with people in the creative and entertainment fields. (Oh man, we aren't as lucky as Schlosser's patients. He coddles them, but he doesn't spare us. His vivid observations about excessive eating and drinking's effects on the human body will make you padlock your fridge and abandon your liquor cabinet.)We learn very early on that one of these patients, famous actor Ralph Meier, is dead. Schlosser is facing the medical board's scrutiny, and Meier's widow, Judith, is incensed. Schlosser relates how this came about by looking back at his Mediterranean vacation, when Meier had invited Schlosser, his wife, and their two beautiful blond daughters to come stay at his summer house. Also there were Judith Meier, their two sons, Judith's mother, and an American filmmaker and his much-younger model/actress girlfriend. These characters––and other people and animals in the neighborhood––are well described in their varying degrees of unhappiness on the road to oblivion, and Schlosser has interesting takes on them.

|

| Just in case you don't know what a weasel looks like |

On Tuesday, I'll tell you about Celeste Ng's Everything I Never Told You (Penguin, June 2014).

No comments:

Post a Comment